Hurricane Juliette was a powerful Pacific hurricane that struck Mexico in September 2001. A long-lived tropical cyclone, Juliette originated from a tropical wave that exited western Africa, the same wave that earlier spawned Atlantic Tropical Depression Nine near Nicaragua on September 19. Two days later, a new tropical depression developed offshore Guatemala, which became Hurricane Juliette by September 22 as it rapidly intensified off western Mexico. On September 24 it strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale, only to weaken due to an eyewall replacement cycle, then re-intensified a day later to attain maximum sustained winds of 230 km/h (145 mph), with a minimum barometric pressure of 923 mbar (27.3 inHg). Juliette weakened as it moved toward the Baja California peninsula, producing hurricane-force winds and torrential rainfall across Baja California Sur. On September 30 after the hurricane had weakened, Juliette made landfall near San Carlos as a minimal tropical storm. After drifting across the Gulf of California, Juliette dissipated on October 3.

Tropical Storm Chris was the fourth tropical storm of the 2006 Atlantic hurricane season. Forming on July 31 in the Atlantic Ocean east of the Leeward Islands from a tropical wave, Chris moved generally to the west-northwest, skirting the northern fringes of the Caribbean islands. Chris was a relatively short-lived storm, reaching a peak intensity with winds at 65 mph (105 km/h) on August 2, while positioned north of St. Martin. The storm gradually weakened before finally dissipating on August 5, near eastern Cuba. Overall impact was minimal, amounting to moderate amounts of rainfall throughout its path. No deaths were reported.

Hurricane Lane was a powerful tropical cyclone which is tied as the ninth-strongest landfalling Pacific hurricane on record. The thirteenth named storm, ninth hurricane, and sixth major hurricane of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season, Lane developed on September 13 from a tropical wave to the south of Mexico. It moved northwestward, parallel to the coast of Mexico, and steadily intensified in an area conducive to further strengthening. After turning to the northeast, Lane attained peak winds of 125 mph (201 km/h), and made landfall in the state of Sinaloa at peak strength. It rapidly weakened and dissipated on September 17, and later brought precipitation to southern part of the U.S. state of Texas.

Hurricane Paul was a Category 2 Pacific hurricane that struck Mexico as a tropical depression in October 2006. The seventeenth named storm and tenth hurricane of the annual hurricane season, Paul developed from an area of disturbed weather on October 21. The cyclone slowly intensified as it moved into an area of warm waters and progressively decreasing wind shear. Paul attained hurricane status on October 23, and later that day the storm reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h), a strong Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale. A strong trough turned the hurricane to the north and northeast into an area of strong vertical shear, and Paul weakened to a tropical storm on October 24. It accelerated northeastward, and after passing a short distance south of Baja California Sur the low level circulation became decoupled from the rest of the convection. Paul weakened to a tropical depression on October 25 a short distance off the coast of Mexico, and after briefly turning away from the coast it made landfall on northwestern Sinaloa on October 26. The depression dissipated shortly thereafter.

Tropical Storm Emilia was a rare tropical cyclone that affected the Baja California Peninsula in July 2006. The sixth tropical depression and fifth tropical storm of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season, it developed on July 21 about 400 miles (640 km) off the coast of Mexico. It moved northward toward the coast, reaching peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) before turning westward and encountering unfavorable conditions. Emilia later turned to the north, passing near Baja California as a strong tropical storm. Subsequently, the storm moved further away from the coast, and on July 27 it dissipated.

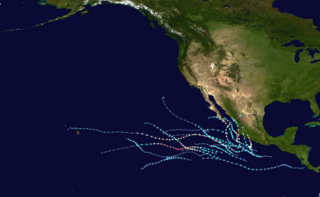

The 2008 Pacific hurricane season was a near-average Pacific hurricane season which featured seventeen named storms, though most were rather weak and short-lived. Only seven storms became hurricanes, of which two intensified into major hurricanes. This season was also the first since 1996 to have no cyclones cross into the central Pacific. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific and on June 1 in the central Pacific. It ended in both regions on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclone formation occurs in these regions of the Pacific. This season, the first system, Tropical Storm Alma, formed on May 29, and the last, Tropical Storm Polo, dissipated on November 5.

Tropical Storm Norman was a weak tropical cyclone that brought heavy rainfall to southwestern Mexico in October 2006. The fifteenth named storm of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season, Norman developed on October 9 from a tropical wave well to the southwest of Mexico. Unfavorable conditions quickly encountered the system, and within two days of forming, Norman dissipated as its remnants turned to the east. Thunderstorms gradually increased again, as it interacted with a disturbance to its east, and on October 15 the cyclone regenerated just off the coast of Mexico. The center became disorganized and quickly dissipated, bringing a large area of moisture which dropped up to 6 inches (150 mm) of rainfall to southwestern Mexico. Rainfall from the storm flooded about 150 houses, of which 20 were destroyed. One person was injured, and initially there were reports of two people missing due to the storm; however, it was not later confirmed.

Tropical Storm Julio was a tropical storm that made landfall on the southern tip of Baja California Sur in August 2008. The eleventh named storm of the 2008 Pacific hurricane season, it developed from a tropical wave on August 23 off the coast of Mexico. It moved parallel to the coast, reaching peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) before moving ashore and weakening. On August 26 it dissipated in the Gulf of California. Julio was the third tropical cyclone to make landfall in the Eastern Pacific tropical cyclone basin during the season, after Tropical Storm Alma, which struck Nicaragua in May, and Tropical Depression Five-E, which moved ashore along southwestern Mexico in July. The storm brought locally heavy rainfall to southern Baja California, killing one person and leaving several towns isolated. Moisture from Julio reached Arizona, producing thunderstorms, including one which damaged ten small planes in Chandler.

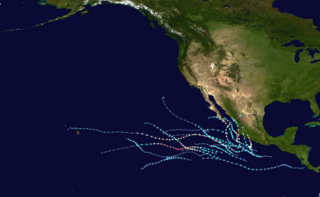

The 2006 Pacific hurricane season was the first above-average season since 1997 which produced twenty-five tropical cyclones, with nineteen named storms, though most were rather weak and short-lived. There were eleven hurricanes, of which six became major hurricanes. Following the inactivity of the previous seasons, forecasters predicted that season would be only slightly above active. It was also the first time since 2003 in which one cyclone of at least tropical storm intensity made landfall. The season officially began on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year.

Hurricane Hernan was the fourth and final tropical cyclone to strike Mexico at hurricane intensity during the 1996 Pacific hurricane season. The thirteenth tropical cyclone, eighth named storm, and fifth hurricane of the season, Hernan developed as a tropical depression from a tropical wave to the south of Mexico on September 30. The depression quickly strengthened, and became Tropical Storm Hernan later that day. Hernan curved north-northwestward the following day, before eventually turning north-northeastward. Still offshore of the Mexican coast on October 2, Hernan intensified into a hurricane. Six hours later, Hernan attained its peak as an 85 mph (140 km/h) Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS). After weakening somewhat, on 1000 UTC October 3, Hurricane Hernan made landfall near Barra de Navidad, Jalisco, with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). Only two hours after landfall, Hernan weakened to a tropical storm. By October 4, Tropical Storm Hernan had weakened into a tropical depression, and dissipated over Nayarit on the following day.

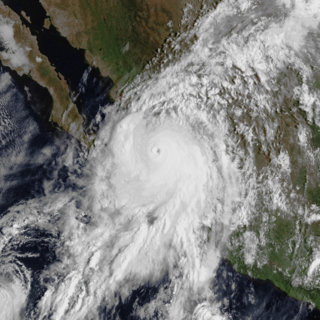

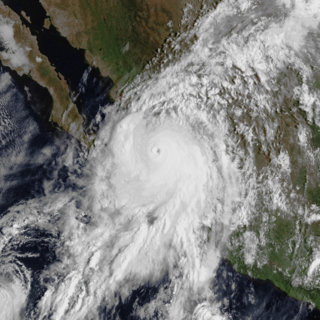

Hurricane Norbert is tied with Hurricane Jimena as the strongest tropical cyclone to strike the west coast of Baja California Sur in recorded history. The fifteenth named storm, seventh hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2008 hurricane season, Norbert originated as a tropical depression from a tropical wave south of Acapulco on October 3. Strong wind shear initially prevented much development, but the cyclone encountered a more favorable environment as it moved westward. On October 5, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Norbert, and the system intensified further to attain hurricane intensity by October 6. After undergoing a period of rapid deepening, Norbert reached its peak intensity as a Category 4 on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, with maximum sustained winds of 135 mph (217 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 945 mbar. As the cyclone rounded the western periphery of a subtropical ridge over Mexico, it began an eyewall replacement cycle which led to steady weakening. Completing this cycle and briefly reintensifying into a major hurricane, a Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, Norbert moved ashore Baja California Sur as a Category 2 hurricane late on October 11. After a second landfall at a weaker intensity the following day, the system quickly weakened over land and dissipated that afternoon.

Tropical Storm Odile was a late season tropical storm that formed during the 2008 Pacific hurricane season and affected parts of southern Mexico. A tropical depression formed on October 8, and became Tropical Storm Odile 18 hours later. The storm paralleled the south coast of Mexico, with the center located only several miles offshore. After peaking in intensity, increasing southeasterly vertical wind shear induced a trend of rapid weakening on the storm. Correspondingly, Odile was downgraded to a tropical depression early on 12 October, subsequently degenerating into a remnant low about 55 mi (85 km) south of Manzanillo, Colima. From thereon, the low proceeded slowly south-southwestward before dissipating on October 13. Since Odile stayed at sea, its effects along coastlines were limited. The most notable damages were caused by flooding along the southern coast of Mexico, mostly in Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero and Michoacán. The exact amount of damage, however, remains unknown, and no fatalities were reported as a result of the storm.

The 2009 Pacific hurricane season was the most active Pacific hurricane season since 1997. The season officially started on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Eastern Pacific tropical cyclone basin; however, tropical cyclone formation is possible at any time of the year. The first system of the season, Tropical Depression One-E, developed on June 18, and the last, Hurricane Neki, dissipated on October 27, keeping activity well within the bounds of the season.

Hurricane Howard was a powerful Category 4 hurricane which produced large swells along the coasts of the Baja California Peninsula and southern California. The cyclone was the eighth named storm, fourth hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2004 Pacific hurricane season. Howard originated out of a tropical wave off the coast of Mexico on August 30. Traveling towards the northwest, the storm gradually strengthened, becoming a hurricane on September 1 and reaching its peak intensity the following day with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h). Decreasing sea surface temperatures then caused the storm to weaken. By September 4, Howard was downgraded to a tropical storm. The next day, it degenerated into a non-convective remnant low-pressure area which persisted for another five days before dissipating over open waters.

Tropical Storm Carlos was the first of five tropical cyclones to make landfall during the 2003 Pacific hurricane season. It formed on June 26 from a tropical wave to the south of Mexico. It quickly strengthened as it approached the coast, and early on June 27 Carlos moved ashore in Oaxaca with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). The storm rapidly deteriorated to a remnant low, which persisted until dissipating on June 29. Carlos brought heavy rainfall to portions of southern Mexico, peaking at 337 mm (13.3 in) in two locations in Guerrero. Throughout its path, the storm damaged about 30,000 houses, with a monetary damage total of 86.7 million pesos. At least nine people were killed throughout the country, seven due to mudslides and two from river flooding; there was also a report of two missing fishermen.

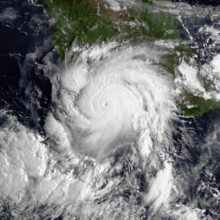

Hurricane Rick was the third-most intense Pacific hurricane on record and the second-most intense tropical cyclone worldwide in 2009, only behind Typhoon Nida. Developing off the southern coast of Mexico on October 15, Rick traversed an area with favorable environmental conditions, favoring rapid intensification, allowing it to become a hurricane within 24 hours of being declared a tropical depression. An eye began to form during the afternoon of October 16; once fully formed, the storm underwent another period of rapid strengthening. During the afternoon of October 17, the storm attained Category 5 status on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Several hours later, Rick attained its peak intensity as the third-strongest Pacific hurricane on record with winds of 180 mph (290 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 906 mbar.

The 2021 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active Pacific hurricane season, with above-average activity in terms of number of named storms, but below-average activity in terms of major hurricanes, as 19 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes formed in all. It also had a near-normal accumulated cyclone energy (ACE). The season officially began on May 15, 2021 in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1, 2021, in the Central Pacific in the Northern Hemisphere. The season ended in both regions on November 30, 2021. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific and are adopted by convention. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as illustrated by the formation of Tropical Storm Andres on May 9, which was the earliest forming tropical storm on record in the Eastern Pacific. Conversely, 2021 was the second consecutive season in which no tropical cyclones formed in the Central Pacific.

Tropical Storm Ileana was a small tropical cyclone that affected western Mexico in early August 2018, causing deadly flooding. The eleventh tropical cyclone and ninth named storm of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season, Ileana originated from a tropical wave that the National Hurricane Center began monitoring on July 26 as the wave left the west coast of Africa. The wave traveled across the Atlantic Ocean with no thunderstorm activity, before crossing into the Eastern Pacific Ocean early on August 4. Rapidly developing, the disturbance organized into a tropical depression on the evening of the same day. Initially, the depression was well-defined, but it soon degraded due to northerly wind shear. Despite the unfavorable conditions, the system began to strengthen on August 5, becoming Tropical Storm Ileana. A day later, on August 6, Ileana began to develop an eyewall structure as it reached its peak intensity with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a pressure of 998 mbar (29.47 inHg). The storm gradually became intertwined with the nearby Hurricane John; over the next day, the circulation of John disrupted Ileana before ultimately absorbing it on August 7.

Hurricane Dolores was a powerful and moderately damaging tropical cyclone whose remnants brought record-breaking heavy rains and strong winds to California. The seventh named storm, fourth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the record-breaking 2015 Pacific hurricane season, Dolores formed from a tropical wave on July 11. The system gradually strengthened, attaining hurricane status on July 13. Dolores rapidly intensified as it neared the Baja California peninsula, finally peaking as a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) on July 15. An eyewall replacement cycle began and cooler sea-surface temperatures rapidly weakened the hurricane, and Dolores weakened to a tropical storm two days later. On July 18, Dolores degenerated into a remnant low west of the Baja California peninsula.

Hurricane Genevieve was a strong tropical cyclone that almost made landfall on the Baja California Peninsula in August 2020. Genevieve was the twelfth tropical cyclone, eighth named storm, third hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2020 Pacific hurricane season. The cyclone formed from a tropical wave that the National Hurricane Center (NHC) first started monitoring on August 10. The wave merged with a trough of low pressure on August 13, and favorable conditions allowed the wave to intensify into Tropical Depression Twelve-E at 15:00 UTC. Just six hours later, the depression became a tropical storm and was given the name Genevieve. Genevieve quickly became a hurricane by August 17, and Genevieve began explosive intensification the next day. By 12:00 UTC on August 18, Genevieve reached its peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 130 mph and a minimum central pressure of 950 millibars (28 inHg). Genevieve began to weaken on the next day, possibly due to cooler waters caused by Hurricane Elida earlier that month. Genevieve weakened below tropical storm status around 18:00 UTC on August 20, as it passed close to Baja California Sur. Soon afterward, Genevieve began to lose its deep convection and became a post-tropical cyclone by 21:00 UTC on August 21, eventually dissipating off the coast of Southern California late on August 24.