Hiragana is a Japanese syllabary, part of the Japanese writing system, along with katakana as well as kanji.

Japanese is an agglutinative, synthetic, mora-timed language with simple phonotactics, a pure vowel system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent. Word order is normally subject–object–verb with particles marking the grammatical function of words, and sentence structure is topic–comment. Its phrases are exclusively head-final and compound sentences are exclusively left-branching. Sentence-final particles are used to add emotional or emphatic impact, or make questions. Nouns have no grammatical number or gender, and there are no articles. Verbs are conjugated, primarily for tense and voice, but not person. Japanese adjectives are also conjugated. Japanese has a complex system of honorifics with verb forms and vocabulary to indicate the relative status of the speaker, the listener, and persons mentioned.

Nihon-shiki is a romanization system for transliterating the Japanese language into the Latin alphabet. Among the major romanization systems for Japanese, it is the most regular one and has an almost one-to-one relation to the kana writing system.

The historicalkanaorthography, or old orthography, refers to the kana orthography in general use until orthographic reforms after World War II; the current orthography was adopted by Cabinet order in 1946. By that point the historical orthography was no longer in accord with Japanese pronunciation. It differs from modern usage in the number of characters and the way those characters are used. There was considerable opposition to the official adoption of the current orthography, on the grounds that the historical orthography conveys meanings better, and some writers continued to use it for many years after.

The dakuten, colloquially ten-ten, is a diacritic most often used in the Japanese kana syllabaries to indicate that the consonant of a syllable should be pronounced voiced, for instance, on sounds that have undergone rendaku.

Wāpuro rōmaji (ワープロローマ字), or kana spelling, is a style of romanization of Japanese originally devised for entering Japanese into word processors while using a Western QWERTY keyboard.

Japanese pitch accent is a feature of the Japanese language that distinguishes words by accenting particular morae in most Japanese dialects. The nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects. For instance, the word for "river" is in the Tokyo dialect, with the accent on the second mora, but in the Kansai dialect it is. A final or is often devoiced to or after a downstep and an unvoiced consonant.

The classical Japanese language, also called "old writing" and sometimes simply called "Medieval Japanese", is the literary form of the Japanese language that was the standard until the early Shōwa period (1926–1989). It is based on Early Middle Japanese, the language as spoken during the Heian period (794–1185), but exhibits some later influences. Its use started to decline during the late Meiji period (1868–1912) when novelists started writing their works in the spoken form. Eventually, the spoken style came into widespread use, including in major newspapers, but many official documents were still written in the old style. After the end of World War II, most documents switched to the spoken style, although the classical style continues to be used in traditional genres, such as haiku and waka. Old laws are also left in the classical style unless fully revised.

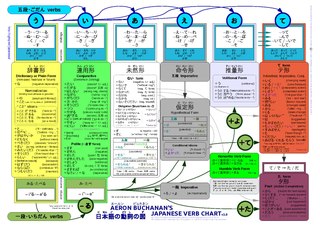

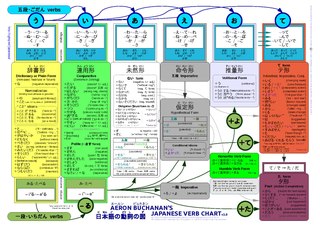

Japanese verbs, like the verbs of many other languages, can be morphologically modified to change their meaning or grammatical function – a process known as conjugation. In Japanese, the beginning of a word is preserved during conjugation, while the ending of the word is altered in some way to change the meaning. Japanese verb conjugations are independent of person, number and gender ; the conjugated forms can express meanings such as negation, present and past tense, volition, passive voice, causation, imperative and conditional mood, and ability. There are also special forms for conjunction with other verbs, and for combination with particles for additional meanings.

Japanese particles, joshi (助詞) or tenioha (てにをは), are suffixes or short words in Japanese grammar that immediately follow the modified noun, verb, adjective, or sentence. Their grammatical range can indicate various meanings and functions, such as speaker affect and assertiveness.

The Tosa dialect is a Japanese Shikoku dialect spoken in central and eastern Kochi Prefecture, including Kochi City. The dialect of the Western region of Kochi Prefecture is called the Hata dialect and is drastically different from the Central and Eastern dialect.

Kanazukai are the orthographic rules for spelling Japanese in kana. All phonographic systems attempt to account accurately the pronunciation in their spellings. However, pronunciation and accents change over time and phonemic distinctions are often lost. Various systems of kanazukai were introduced to deal with the disparity between the written and spoken versions of Japanese.

The Ibaraki dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Ibaraki Prefecture. It is noted for its distinctive use of the sentence-ending particles べ (be) and っぺ (ppe) and an atypical intonation pattern that rises in neutral statements and falls in questions. It is also noted for its merging of certain vowels, frequent consonant voicing, and a relatively fast rate of speech.

The grammatical particles used in the Kagoshima dialects of Japanese have many features in common with those of other dialects spoken in Kyūshū, with some being unique to the Kagoshima dialects. Like standard Japanese particles, they act as suffixes, adpositions or words immediately following the noun, verb, adjective or phrase that they modify, and are used to indicate the relationship between the various elements of a sentence.

The Shizuoka dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Shizuoka Prefecture. In a narrow sense, this can refer purely to the Central Shizuoka dialect, whilst a broader definition encompasses all Shizuoka dialects. This article will focus on all dialects found in the prefecture.

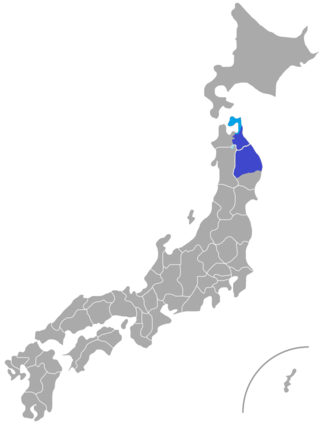

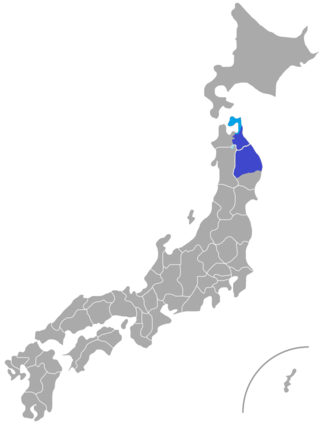

The Nanbudialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in an area corresponding to the former domains of Morioka and Hachinohe in northern Tohoku, governed by the Nanbu clan during the Edo period. It is classified as a Northern Tohoku dialect of the wider Tohoku dialect group.

The Chikuzen dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in western Fukuoka Prefecture in an area corresponding to the former Chikuzen Province. It is classified as a Hichiku dialect of the wider Kyushu dialect of Japanese, although the eastern part of the accepted dialect area has more similarities with the Buzen dialect, and the Asakura District in the south bears a stronger resemblance to the Chikugo dialect. The Chikuzen dialect is considered the wider dialect to which the Hakata dialect, the Fukuoka dialect and the Munakata dialect belong.

The Nagasaki dialect is the name given to the dialect of Japanese spoken on the mainland part of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu. It is a major dialect of the wider Hichiku group of Kyushu Japanese, with similarities to the Chikuzen and Kumamoto dialects, among others. It is one of the better known Hichiku dialects within Japan, with various historical proverbs that relate to its regional flavour.

The Kishū dialect is a Kansai dialect of Japanese spoken in the former province of Kino, in what is now Wakayama Prefecture and southern Mie Prefecture. In Wakayama Prefecture the dialect may also be referred to as the Wakayama dialect.

The Okuyoshino dialect is a Kansai dialect of Japanese spoken in several villages in the Okuyoshino region of southern Nara Prefecture. It is well-known as a language island, with various rare and unique characteristics.