|

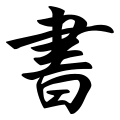

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

JSL is a romanization system for transcribing the Japanese language into the Latin script. It was devised by Eleanor Jorden for (and named after) her 1987 book Japanese: The Spoken Language . The system is based on Kunrei-shiki romanization. [1] Japanese Yale is a less well-known alternative name for the JSL system.

| Example: tat-u | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conjugation | JSL | Hepburn |

| Mizen 1 | tat-a- | tat-a- |

| Mizen 2 | tat-o- | tat-o- |

| Ren'yô | tat-i- | tach-i- |

| Syûsi | tat-u. | tats-u. |

| Rentai | tat-u- | tats-u- |

| Katei | tat-e- | tat-e- |

| Meirei | tat-e. | tat-e. |

It is designed for teaching spoken Japanese, and so, it follows Japanese phonology fairly closely. For example, different conjugations of a verb may be achieved by changing the final vowel (as in the chart on the right), thus "bear[ing] a direct relation to Japanese structure" (in Jorden's words [1] ), whereas the common Hepburn romanization may require exceptions in some cases, to more clearly illustrate pronunciation to native English speakers.

JSL differs from Hepburn, particularly in that it uses doubled vowels, rather than macrons, to represent the long vowels /oː/ and /ɯː/. Tokyo (Tōkyō) and Osaka (Ōsaka), for instance, would be written (Tookyoo) and (Oosaka) in JSL. Also, JSL represents ⟨ん⟩, the syllabic n, as an "n" with a macron over it, (n̄), to avoid the practice that other systems use of sometimes writing (n) and sometimes (n') depending on the presence of a following vowel or (y).

There is a close tie between Japanese pronunciation and JSL, where one consistent symbol is given for each Japanese phoneme. This means that it does depart from Japanese orthography somewhat, as おう is romanized as (oo) when it indicates a long /oː/, but as (ou) when it indicates two distinct vowel sounds, such as in (omou) for 思う (おもう). Similarly, (ei) is reserved for the pronunciation [ei] only, whereas other romanization systems (including Hepburn) follow the hiragana orthography, therefore making it impossible to tell whether [eː] or [ei] are represented. [2] It also distinguishes between (g), which is used when only a /ɡ/ sound is possible, and (ḡ), which is used when a velar nasal sound [ ŋ ] (the "ng" in the English word "singer") is also possible. The particles は and へ are romanized (wa) and (e), by their pronunciation. However, like Kunrei-shiki and Nihon-shiki, JSL does not distinguish between allophones in Japanese which are close to different phonemes in English.

JSL indicates the pitch accent of each mora. A vowel with an acute accent (´) denotes the first high-pitch mora, a grave accent (`) marks the last high-pitch mora, and a circumflex (ˆ) marks the only high-pitch mora in a word. In this system 日本 'Japan' would be written (nihôn̄) and 二本 'two (sticks)' as (nîhon̄), 端です 'It's the edge' would be (hasí dèsu) (standing for /hasidesu/[hàɕides(ɯ̀ᵝ)]. [3] (This is why doubled vowels must be used instead of macrons.)