Japanese pitch accent is a feature of the Japanese language that distinguishes words by accenting particular morae in most Japanese dialects. The nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects. For instance, the word for "river" is in the Tokyo dialect, with the accent on the second mora, but in the Kansai dialect it is. A final or is often devoiced to or after a downstep and an unvoiced consonant.

The Tosa dialect is a Japanese Shikoku dialect spoken in central and eastern Kochi Prefecture, including Kochi City. The dialect of the Western region of Kochi Prefecture is called the Hata dialect and is drastically different from the Central and Eastern dialect.

The Saga dialect is a dialect of the Japanese language widely spoken in Saga Prefecture and some other areas, such as Isahaya. It is influenced by Kyushu dialect and Hichiku dialect. Saga-ben is further divided by accents centered on individual towns.

Modern kana usage is the present official kanazukai. Also known as new kana usage, it is derived from historical usage.

The Ibaraki dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Ibaraki Prefecture. It is noted for its distinctive use of the sentence-ending particles べ (be) and っぺ (ppe) and an atypical intonation pattern that rises in neutral statements and falls in questions. It is also noted for its merging of certain vowels, frequent consonant voicing, and a relatively fast rate of speech.

The grammatical particles used in the Kagoshima dialects of Japanese have many features in common with those of other dialects spoken in Kyūshū, with some being unique to the Kagoshima dialects. Like standard Japanese particles, they act as suffixes, adpositions or words immediately following the noun, verb, adjective or phrase that they modify, and are used to indicate the relationship between the various elements of a sentence.

The Tochigi dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Tochigi prefecture. It is classified along with the Ibaraki dialect as an East Kanto dialect, but due to possessing various shared phonological and grammatical features with the neighbouring Fukushima dialect to the north, many scholars consider it instead as part of the wider Tohoku dialect. It has notable differences within the prefecture depending on region, and in some parts of the southwest of the prefecture a separate dialect, the Ashikaga dialect, is spoken.

The Gunma dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Gunma Prefecture.

The Kanagawa dialect is the term used to describe the Japanese dialects spoken in Kanagawa Prefecture. As there is no single unified dialect throughout the prefecture, it is a collective term, with some of the regional dialects spoken including: the Sōshū dialect, the Yokohama dialect, the Hadano dialect and Shōnan dialect, among others.

The Shizuoka dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Shizuoka Prefecture. In a narrow sense, this can refer purely to the Central Shizuoka dialect, whilst a broader definition encompasses all Shizuoka dialects. This article will focus on all dialects found in the prefecture.

The Kaga dialect is a Japanese Hokuriku dialect spoken south of Kahoku in the Kaga region of Ishikawa Prefecture.

The Bingo dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in the Bingo Region of eastern Hiroshima Prefecture. It is part of the Chūgoku dialect group.

The Inshū dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in the Inaba region of eastern Tottori Prefecture. It may also be called the Tottori dialect, though this is not to be confused with other dialects that are also spoken in the prefecture, namely the Kurayoshi and West Hōki dialects. It is considered an East San’in dialect of the wider Chūgoku dialect group. In parts of northern Hyōgo Prefecture that neighbour Tottori, specifically in the Tajima region, a similar dialect to the Inshu dialect is spoken. It bears many similarities to its close relative, the Kurayoshi dialect of central Tottori but retains some notable differences.

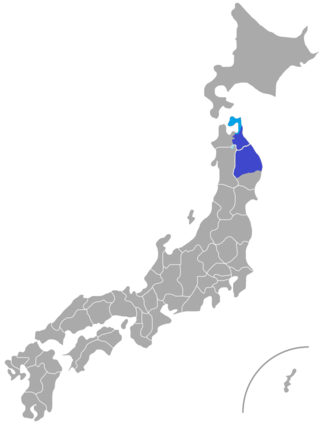

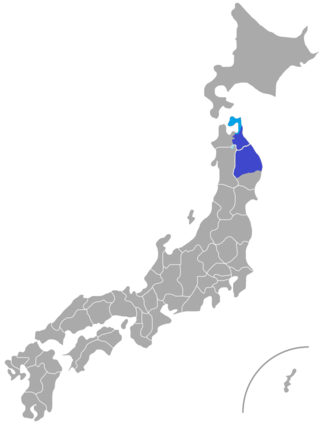

The Nanbudialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in an area corresponding to the former domains of Morioka and Hachinohe in northern Tohoku, governed by the Nanbu clan during the Edo period. It is classified as a Northern Tohoku dialect of the wider Tohoku dialect group.

The Narada dialect was a Japanese dialect spoken in the village of Narada, Hayakawa, located in Yamanashi Prefecture. Having formerly been isolated for centuries from surrounding areas, the dialect was considered a language island within the Tokai-Tosan dialect group, possessing various traits unique to Narada.

The Nairiku dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in the eastern half of Yamagata Prefecture. It belongs to the Southern Tohoku dialect group.

The Northern Izu Archipelagodialects are dialects of Japanese spoken on the inhabited islands north of Mikura-jima in the Izu Archipelago, part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. The various dialects are classified as Eastern Japanese, and are most similar to the Izu dialect of mainland Honshū, but as islands have also developed unique traits which can vary considerably from island to island. On islands with large numbers of migrants from the mainland, such as To-shima, there is increasing standardisation of speech towards the common standard.

The Chikuzen dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in western Fukuoka Prefecture in an area corresponding to the former Chikuzen Province. It is classified as a Hichiku dialect of the wider Kyushu dialect of Japanese, although the eastern part of the accepted dialect area has more similarities with the Buzen dialect, and the Asakura District in the south bears a stronger resemblance to the Chikugo dialect. The Chikuzen dialect is considered the wider dialect to which the Hakata dialect, the Fukuoka dialect and the Munakata dialect belong.

The Kishū dialect is a Kansai dialect of Japanese spoken in the former Kii Province, in what is now Wakayama Prefecture and southern Mie Prefecture. In Wakayama Prefecture, the dialect may also be referred to as the Wakayama dialect.

The Okuyoshino dialect is a Kansai dialect of Japanese spoken in several villages in the Okuyoshino region of southern Nara Prefecture. It is well-known as a language island, with various rare and unique characteristics.