|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

In Japanese language, Ryakuji (Japanese : 略字 "abbreviated characters", or 筆写略字hissha ryakuji, meaning "handwritten abbreviated characters") are colloquial simplifications of kanji.

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

In Japanese language, Ryakuji (Japanese : 略字 "abbreviated characters", or 筆写略字hissha ryakuji, meaning "handwritten abbreviated characters") are colloquial simplifications of kanji.

Ryakuji are not covered in the Kanji Kentei, nor are they officially recognized (most ryakuji are not present in Unicode). However, some abbreviated forms of hyōgaiji (表外字, characters not included in the tōyō or jōyō kanji lists) included in the JIS standards which conform to the shinjitai simplifications are included in Level pre-1 and above of the Kanji Kentei (e.g., 餠→餅, 摑→掴), as well as some other allowances for alternate ways of writing radicals and alternate forms. Some ryakuji were adopted as shinjitai.

Some simplifications are commonly used as special Japanese typographic symbols. These include:

Of these, only 〆 for 締 and ヶ for 箇 are generally recognized as being simplifications of kanji characters.

Replacements of complex characters by simpler standard characters (whether related or not) is instead a different phenomenon, kakikae . For example, in writing 年齢43歳 as 年令43才 (nenrei 43 sai "age 43 years"), 齢 is replaced by the component 令 and 歳 is replaced by 才, in both cases with the same pronunciation but different meanings. The replacement of 齢 by 令 is a graphic simplification (keeping the phonetic), while 歳 and 才 are graphically unrelated, but in both cases this is simply considered a replacement character, not a simplified form. Other examples include simplifying 醤油shōyu (soy sauce) to 正油.

Compare this to simplified Chinese.

Ryakuji are primarily used in individual memos, notes and other such forms of handwriting. Their use has declined in recent years, possibly due to the emergence of computer technology and advanced input methods that allow equally fast input of both simple and complex characters. Despite this, the ryakuji for 門 (mon, kado; gate) and for characters using the radical 門 are still widely used in handwriting. [1]

In all cases discussed in the other sections of this article, individual characters are simplified, but separate characters are not merged. There are rare cases of single-character abbreviations for multiple-character words or phrases, such as 圕 for 圖書館, 図書館 toshokan, "library", but this is very unusual; see polysyllabic Chinese characters for this phenomenon in Chinese, where it is more common.

Of these, several are commonly seen in signs: 門 (2), 品 (12), 器 (12) are very commonly seen, particularly simplifying 間 in store signs, while 第 (1) and 曜 (5) are also relatively common, as is 𩵋 for 魚 (as in 点 (3)). Other characters are less commonly seen in public, instead being primarily found in private writing.

Omitting components is a general principle, and the resulting character is often not a standard character, as in 傘→仐.

If the resulting character is a standard character with the same reading (common if keeping the phonetic), this is properly kakikae instead, but if it is simply a graphic simplification (with a different reading) or the resulting character is not standard, this is ryakuji. One of the most common examples is 巾 for 幅haba "width". Often the result would be ambiguous in isolation, but is understandable from context. This is particularly common in familiar compounds, such as in the following examples:

In some cases, a component has been simplified when part of other characters, but has not been simplified in isolation, or has been simplified in some characters but not others. In that case, simplifying it in isolation can be used as common ryakuji. For example, 卒 is used in isolation, but in compounds has been simplified to 卆 , such as 醉 to 酔. Using 卆 in isolation, such as when writing 新卒shin-sotsu "newly graduated" as 新卆, is unofficial ryakuji. As another example, 專 has been simplified to 云 in some characters, such as 傳 to 伝, but only to 専 in isolation or other characters. Thus simplifying the 専 in 薄 (bottom part 溥) to 云 is found in ryakuji.

More unusual examples come from calligraphic abbreviations, or more formally from printed forms of calligraphic forms: a standard character is first written in a calligraphic (草書, grass script) form, then this is converted back to print script (楷書) in a simplified form. This is the same principle as graphical simplifications such as 學→学, and of various simplifications above, such as 第→㐧. A conspicuous informal example is 喜→㐂 (3 copies of the character for 7: 七), which is rather frequently seen on store signs. Other examples include 鹿→𢈘; and replacing the center of 風 with two 丶, as in the bottom of 冬. 御 has various such simplifications. In Niigata (新潟), the second character 潟 is rare and complex, and is thus simplified as 潟→泻(氵写).

Derived characters accordingly also have derived ryakuji, as in these characters derived from 門:

Similarly, the 魚→𩵋 simplification is often used in fish compounds, such as 鮨 sushi, particularly in signs.

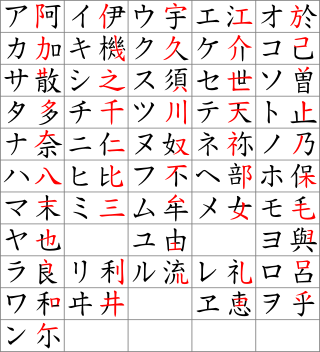

Some ryakuji are simplified phono-semantic characters, retaining a radical as semantic and replacing the rest of the character with a katakana phonetic for the on reading, e.g., 議 (20 strokes) may be simplified as 言 (semantic) + ギ (phonetic gi for on reading):

Another example is 層sō, replacing the 曽 by ソso.

This may also be done using Latin characters; for example, the character 憲 (as used in 憲法kenpō, "constitution") may be simplified to "宀K": the radical 宀 placed over the letter K; this is particularly common in law school. Similarly, 慶應 (Keiō) as in Keio University may be simplified to "广K广O": the letters K and O respectively placed inside the radical 广. In this case the pronunciation of "KO" (as an initialism) sounds like the actual name "Keiō", hence the use.

The character 機 has a number of ryakuji, as it is a commonly used character with many strokes (16 strokes); in addition to the above phono-semantic simplification, it also has a number of purely graphical simplifications:

Hiragana is a Japanese syllabary, part of the Japanese writing system, along with katakana as well as kanji.

Katakana is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana, kanji and in some cases the Latin script.

Han unification is an effort by the authors of Unicode and the Universal Character Set to map multiple character sets of the Han characters of the so-called CJK languages into a single set of unified characters. Han characters are a feature shared in common by written Chinese (hanzi), Japanese (kanji), Korean (hanja) and Vietnamese.

Iteration marks are characters or punctuation marks that represent a duplicated character or word.

Man'yōgana is an ancient writing system that uses Chinese characters to represent the Japanese language. It was the first known kana system to be developed as a means to represent the Japanese language phonetically. The date of the earliest usage of this type of kana is not clear, but it was in use since at least the mid-7th century. The name "man'yōgana" derives from the Man'yōshū, a Japanese poetry anthology from the Nara period written with man'yōgana.

In the Japanese writing system, hentaigana are variant forms of hiragana.

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalized Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.

In modern Japanese, ateji principally refers to kanji used to phonetically represent native or borrowed words with less regard to the underlying meaning of the characters. This is similar to man'yōgana in Old Japanese. Conversely, ateji also refers to kanji used semantically without regard to the readings.

The chōonpu, also known as chōonkigō (長音記号), onbiki (音引き), bōbiki (棒引き), or Katakana-Hiragana Prolonged Sound Mark by the Unicode Consortium, is a Japanese symbol that indicates a chōon, or a long vowel of two morae in length. Its form is a horizontal or vertical line in the center of the text with the width of one kanji or kana character. It is written horizontally in horizontal text and vertically in vertical text. The chōonpu is usually used to indicate a long vowel sound in katakana writing, rarely in hiragana writing, and never in romanized Japanese. The chōonpu is a distinct mark from the dash, and in most Japanese typefaces it can easily be distinguished. In horizontal writing it is similar in appearance to, but should not be confused with, the kanji character 一 ("one").

Shinjitai are the simplified forms of kanji used in Japan since the promulgation of the Tōyō Kanji List in 1946. Some of the new forms found in shinjitai are also found in simplified Chinese characters, but shinjitai is generally not as extensive in the scope of its modification.

き, in hiragana, キ in katakana, is one of the Japanese kana, which each represent one mora. Both represent and are derived from a simplification of the 幾 kanji. The hiragana character き, like さ, is drawn with the lower line either connected or disconnected.

Wi is an obsolete Japanese kana, which is normally pronounced in current-day Japanese. The combination of a W-column kana letter with ゐ゙ in hiragana was introduced to represent in the 19th century and 20th century. It is presumed that 'ゐ' represented, and that 'ゐ' and 'い' represented distinct pronunciations before merging to sometime between the Kamakura and Taishō periods. Along with the kana for we, this kana was deemed obsolete in Japanese with the orthographic reforms of 1946, to be replaced by 'い/イ' in all contexts. It is now rare in everyday usage; in onomatopoeia and foreign words, the katakana form 'ウィ' (U-[small-i]) is used for the mora.

Chinese characters may have several variant forms—visually distinct glyphs that represent the same underlying meaning and pronunciation. Variants of a given character are allographs of one another, and many are directly analogous to allographs present in the English alphabet, such as the double-storey ⟨a⟩ and single-storey ⟨ɑ⟩ variants of the letter A, with the latter more commonly appearing in handwriting. Some contexts require usage of specific variants.

The small ke is a Japanese character, typographically a small form of the katakana character ケke.

Hyōgaiji, also known as hyōgai kanji (表外漢字), is a term for Japanese kanji outside the two major lists of jōyō kanji, which are taught in primary and secondary school, and the jinmeiyō kanji, which are additional kanji that are officially allowed for use in personal names. The term jōyōgai kanji (常用外漢字) is also encountered, but it designates all the kanji outside the list of jōyō kanji, including the jinmeiyō kanji.

The Japanese script reform is the attempt to correlate standard spoken Japanese with the written word, which began during the Meiji period. This issue is known in Japan as the kokugo kokuji mondai. The reforms led to the development of the modern Japanese written language, and explain the arguments for official policies used to determine the usage and teaching of kanji rarely used in Japan.

JIS X 0208 is a 2-byte character set specified as a Japanese Industrial Standard, containing 6879 graphic characters suitable for writing text, place names, personal names, and so forth in the Japanese language. The official title of the current standard is 7-bit and 8-bit double byte coded KANJI sets for information interchange. It was originally established as JIS C 6226 in 1978, and has been revised in 1983, 1990, and 1997. It is also called Code page 952 by IBM. The 1978 version is also called Code page 955 by IBM.

A Japanese rebus monogram is a monogram in a particular style, which spells a name via a rebus, as a form of Japanese wordplay or visual pun. Today they are most often seen in corporate logos or product logos.

Braille Kanji is a system of braille for transcribing written Japanese. It was devised in 1969 by Tai'ichi Kawakami, a teacher at the Osaka School for the Blind, and was still being revised in 1991. It supplements Japanese Braille by providing a means of directly encoding kanji characters without having to first convert them to kana. It uses an 8-dot braille cell, with the lower six dots corresponding to the cells of standard Japanese Braille, and the upper two dots indicating the constituent parts of the kanji. The upper dots are numbered 0 and 7, the opposite convention of 8-dot braille in Western countries, where the extra dots are added to the bottom of the cell. A kanji will be transcribed by anywhere from one to three braille cells.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(March 2011) |