Related Research Articles

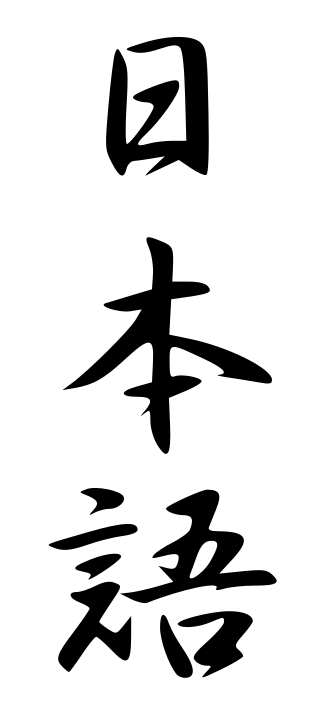

Japanese is the principal language of the Japonic language family spoken by the Japanese people. It has around 123 million speakers, primarily in Japan, the only country where it is the national language, and within the Japanese diaspora worldwide.

Japanese is an agglutinative, synthetic, mora-timed language with simple phonotactics, a pure vowel system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent. Word order is normally subject–object–verb with particles marking the grammatical function of words, and sentence structure is topic–comment. Its phrases are exclusively head-final and compound sentences are exclusively left-branching. Sentence-final particles are used to add emotional or emphatic impact, or make questions. Nouns have no grammatical number or gender, and there are no articles. Verbs are conjugated, primarily for tense and voice, but not person. Japanese adjectives are also conjugated. Japanese has a complex system of honorifics with verb forms and vocabulary to indicate the relative status of the speaker, the listener, and persons mentioned.

Animacy is a grammatical and semantic feature, existing in some languages, expressing how sentient or alive the referent of a noun is. Widely expressed, animacy is one of the most elementary principles in languages around the globe and is a distinction acquired as early as six months of age.

In linguistics, agglutination is a morphological process in which words are formed by stringing together morphemes, each of which corresponds to a single syntactic feature. Languages that use agglutination widely are called agglutinative languages. For example, in the agglutinative language of Turkish, the word evlerinizden consists of the morphemes ev-ler-i-n-iz-den. Agglutinative languages are often contrasted with isolating languages, in which words are monomorphemic, and fusional languages, in which words can be complex, but morphemes may correspond to multiple features.

Okurigana are kana suffixes following kanji stems in Japanese written words. They serve two purposes: to inflect adjectives and verbs, and to force a particular kanji to have a specific meaning and be read a certain way. For example, the plain verb form 見る inflects to past tense 見た, where 見 is the kanji stem, and る and た are okurigana, written in hiragana script. With very few exceptions, okurigana are only used for kun'yomi, not for on'yomi, as Chinese morphemes do not inflect in Japanese, and their pronunciation is inferred from context, since many are used as parts of compound words (kango).

In linguistic typology, a null-subject language is a language whose grammar permits an independent clause to lack an explicit subject; such a clause is then said to have a null subject.

Japanese pitch accent is a feature of the Japanese language that distinguishes words by accenting particular morae in most Japanese dialects. The nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects. For instance, the word for "river" is in the Tokyo dialect, with the accent on the second mora, but in the Kansai dialect it is. A final or is often devoiced to or after a downstep and an unvoiced consonant.

Japanese particles, joshi (助詞) or tenioha (てにをは), are suffixes or short words in Japanese grammar that immediately follow the modified noun, verb, adjective, or sentence. Their grammatical range can indicate various meanings and functions, such as speaker affect and assertiveness.

A topic marker is a grammatical particle used to mark the topic of a sentence. It is found in Japanese, Korean, Sorani, Quechua, Ryukyuan, Imonda and, to a limited extent, Classical Chinese. It often overlaps with the subject of a sentence, causing confusion for learners, as most other languages lack it. It differs from a subject in that it puts more emphasis on the item and can be used with words in other roles as well.

In linguistic typology, object–subject–verb (OSV) or object–agent–verb (OAV) is a classification of languages, based on whether the structure predominates in pragmatically neutral expressions. An example of this would be "Oranges Sam ate".

The Japanese language has different ways of expressing the possessive relation. There are several "verbal possessive" forms based on verbs with the sense of "to possess" or "to have" or "to own". An alternative is the use of the particle no (の) between two nouns or noun phrases.

Finger 5 was a Japanese pop group, initially composed of the four Okinawan Tamamoto brothers Kazuo, Mitsuo, Masao, Akira, and sister Taeko. Their greatest hit was "Koi no Dial 6700".

The Ibaraki dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Ibaraki Prefecture. It is noted for its distinctive use of the sentence-ending particles べ (be) and っぺ (ppe) and an atypical intonation pattern that rises in neutral statements and falls in questions. It is also noted for its merging of certain vowels, frequent consonant voicing, and a relatively fast rate of speech.

The grammatical particles used in the Kagoshima dialects of Japanese have many features in common with those of other dialects spoken in Kyūshū, with some being unique to the Kagoshima dialects. Like standard Japanese particles, they act as suffixes, adpositions or words immediately following the noun, verb, adjective or phrase that they modify, and are used to indicate the relationship between the various elements of a sentence.

The Hachijō language shares much of its grammar with its sister language of Japanese—having both descended from varieties of Old Japanese—as well as with its more distant relatives in the Ryukyuan language family. However, Hachijō grammar includes a substantial number of distinguishing features from modern Standard Japanese, both innovative and archaic.

The Shizuoka dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in Shizuoka Prefecture. In a narrow sense, this can refer purely to the Central Shizuoka dialect, whilst a broader definition encompasses all Shizuoka dialects. This article will focus on all dialects found in the prefecture.

The Kaga dialect is a Japanese Hokuriku dialect spoken south of Kahoku in the Kaga region of Ishikawa Prefecture.

The Chikuzen dialect is a Japanese dialect spoken in western Fukuoka Prefecture in an area corresponding to the former Chikuzen Province. It is classified as a Hichiku dialect of the wider Kyushu dialect of Japanese, although the eastern part of the accepted dialect area has more similarities with the Buzen dialect, and the Asakura District in the south bears a stronger resemblance to the Chikugo dialect. The Chikuzen dialect is considered the wider dialect to which the Hakata dialect, the Fukuoka dialect and the Munakata dialect belong.

The Nagasaki dialect is the name given to the dialect of Japanese spoken on the mainland part of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu. It is a major dialect of the wider Hichiku group of Kyushu Japanese, with similarities to the Chikuzen and Kumamoto dialects, among others. It is one of the better known Hichiku dialects within Japan, with various historical proverbs that relate to its regional flavour.

The Kishū dialect is a Kansai dialect of Japanese spoken in the former province of Kino, in what is now Wakayama Prefecture and southern Mie Prefecture. In Wakayama Prefecture the dialect may also be referred to as the Wakayama dialect.

References

- ↑ Frellesvig, Bjarke (2001). "A Common Korean and Japanese Copula". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 10 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1023/A:1026512817255. ISSN 0925-8558. JSTOR 20100791. S2CID 118327652.

- ↑ Hamilton-Levi, William (2013). "Noun Particle Phenomena in Korean".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)