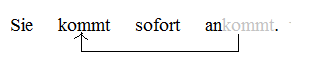

In linguistics, an affix is a morpheme that is attached to a word stem to form a new word or word form. The main two categories are derivational and inflectional affixes. Derivational affixes, such as un-, -ation, anti-, pre- etc., introduce a semantic change to the word they are attached to. Inflectional affixes introduce a syntactic change, such as singular into plural, or present simple tense into present continuous or past tense by adding -ing, -ed to an English word. All of them are bound morphemes by definition; prefixes and suffixes may be separable affixes.

In linguistics, a copula /‘kɒpjələ/ is a word or phrase that links the subject of a sentence to a subject complement, such as the word is in the sentence "The sky is blue" or the phrase was not being in the sentence "It was not being cooperative." The word copula derives from the Latin noun for a "link" or "tie" that connects two different things.

In morphology and syntax, a clitic is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a word, but depends phonologically on another word or phrase. In this sense, it is syntactically independent but phonologically dependent—always attached to a host. A clitic is pronounced like an affix, but plays a syntactic role at the phrase level. In other words, clitics have the form of affixes, but the distribution of function words.

Swiss German is any of the Alemannic dialects spoken in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and in some Alpine communities in Northern Italy bordering Switzerland. Occasionally, the Alemannic dialects spoken in other countries are grouped together with Swiss German as well, especially the dialects of Liechtenstein and Austrian Vorarlberg, which are closely associated to Switzerland's.

Russian grammar employs an Indo-European inflexional structure, with considerable adaptation.

Although not used in general linguistic theory, the term preverb is used in Caucasian, Caddoan, Athabaskan, and Algonquian linguistics to describe certain elements prefixed to verbs. In the context of Indo-European languages, the term is usually used for separable verb prefixes.

Tzeltal or Tseltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

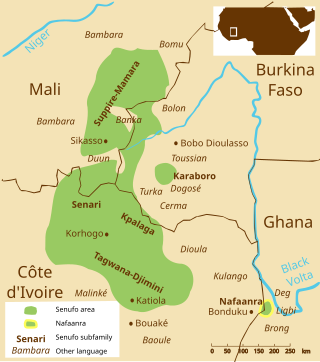

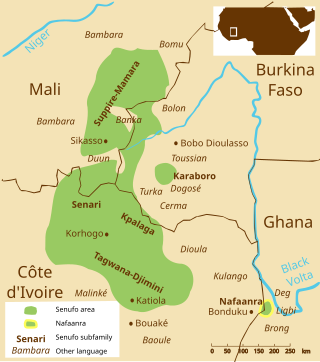

Nafaanra, also known as Nafanan or Nafana, is a Senufo language spoken in northwest Ghana, along the border with Ivory Coast, east of Bondoukou. It is spoken by approximately 90,000 people. Its speakers call themselves Nafana, but others call them Banda or Mfantera. Like other Senufo languages, Nafaanra is a tonal language. It is somewhat of an outlier in the Senufo language group, with the geographically-closest relatives, the Southern Senufo Tagwana–Djimini languages, approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) to the west, on the other side of Comoé National Park.

The Onondaga language is the language of the Onondaga First Nation, one of the original five constituent tribes of the League of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee).

Swampy Cree is a variety of the Algonquian language, Cree. It is spoken in a series of Swampy Cree communities in northern Manitoba, central northeast of Saskatchewan along the Saskatchewan River and along the Hudson Bay coast and adjacent inland areas to the south and west, and Ontario along the coast of Hudson Bay and James Bay. Within the group of dialects called "West Cree", it is referred to as an "n-dialect", as the variable phoneme common to all Cree dialects appears as "n" in this dialect.

Yiddish grammar is the system of principles which govern the structure of the Yiddish language. This article describes the standard form laid out by YIVO while noting differences in significant dialects such as that of many contemporary Hasidim. As a Germanic language descended from Middle High German, Yiddish grammar is fairly similar to that of German, though it also has numerous linguistic innovations as well as grammatical features influenced by or borrowed from Hebrew, Aramaic, and various Slavic languages.

German verbs may be classified as either weak, with a dental consonant inflection, or strong, showing a vowel gradation (ablaut). Both of these are regular systems. Most verbs of both types are regular, though various subgroups and anomalies do arise; however, textbooks for learners often class all strong verbs as irregular. The only completely irregular verb in the language is sein. There are more than 200 strong and irregular verbs, but just as in English, there is a gradual tendency for strong verbs to become weak.

German verbs are conjugated depending on their use: as in English, they are modified depending on the persons (identity) and number of the subject of a sentence, as well as depending on the tense and mood.

This article explains the conjugation of Dutch verbs.

This article summarizes grammar in the Hawaiian language.

Pashto is an S-O-V language with split ergativity. Adjectives come before nouns. Nouns and adjectives are inflected for gender (masc./fem.), number (sing./plur.), and case. The verb system is very intricate with the following tenses: Present; simple past; past progressive; present perfect; and past perfect. In any of the past tenses, Pashto is an ergative language; i.e., transitive verbs in any of the past tenses agree with the object of the sentence. The dialects show some non-standard grammatical features, some of which are archaisms or descendants of old forms.

Torricelli, Anamagi or Lou, is a Torricelli language of East Sepik province, Papua New Guinea. Drinfield describes it as containing three distinct, but related languages: Mukweym, Orok, and Aro.

Talise is a Southeast Solomonic language native to Guadalcanal with a speaker population of roughly 13,000. While some consider Talise to be its own language, others use it as a blanket term to group the closely related dialects of Poleo, Koo, Malagheti, Moli, and Tolo. It is a branch of the Proto-Guadalcanal family, which forms part of the Southeast Solomons language group.

Neverver (Nevwervwer), also known as Lingarak, is an Oceanic language. Neverver is spoken in Malampa Province, in central Malekula, Vanuatu. The names of the villages on Malekula Island where Neverver is spoken are Lingarakh and Limap.

In the traditional grammar of Modern English, a phrasal verb typically constitutes a single semantic unit consisting of a verb followed by a particle, sometimes collocated with a preposition.