The Weather Prediction Center (WPC), located in College Park, Maryland, is one of nine service centers under the umbrella of the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), a part of the National Weather Service (NWS), which in turn is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the U.S. Government. Until March 5, 2013, the Weather Prediction Center was known as the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (HPC). The Weather Prediction Center serves as a center for quantitative precipitation forecasting, medium range forecasting, and the interpretation of numerical weather prediction computer models.

The January 2008 North American storm complex was a powerful Pacific extratropical cyclone that affected a large portion of North America, primarily stretching from western British Columbia to near the Tijuana, Mexico area, starting on January 3, 2008. The system was responsible for flooding rains across many areas in California along with very strong winds locally exceeding hurricane force strength as well as heavy mountain snows across the Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountain chains as well as those in Idaho, Utah and Colorado. The storms were responsible for the death of at least 12 people across three states, and extensive damage to utility services as well, as damage to some other structures. The storm was also responsible for most of the January 2008 tornado outbreak from January 7–8.

The October 2009 North American storm complex was a powerful extratropical cyclone that was associated with the remnants of Typhoon Melor, which brought extreme amounts of rainfall to California. The system started out as a weak area of low pressure, that formed in the northern Gulf of Alaska on October 7. Late on October 11, the system quickly absorbed Melor's remnant moisture, which resulted in the system strengthening significantly offshore, before moving southeastward to impact the West Coast of the United States, beginning very early on October 13. Around the same time, an atmospheric river opened up, channeling large amounts of moisture into the storm, resulting in heavy rainfall across California and other parts of the Western United States. The storm caused at least $8.861 million in damages across the West Coast of the United States.

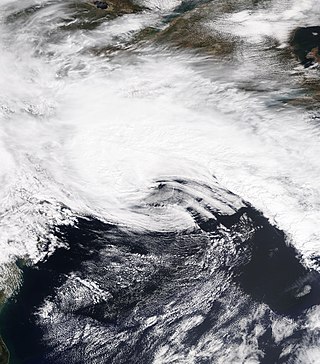

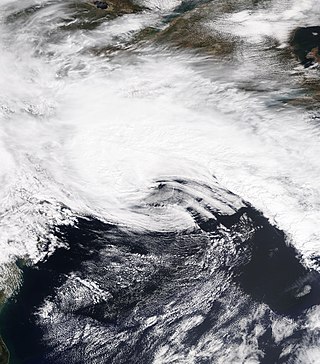

The January 2012 Pacific Northwest snowstorm was a large extratropical cyclone that brought record snowfall to the Pacific Northwest in January 2012. The storm produced very large snowfall totals, reaching up to 50 inches (1,300 mm) in Oregon. A 110 mph (180 km/h) wind gust was reported at Otter Rock, Oregon. A mother and child were killed in Oregon after the car they were in slid into a creek, while a man was killed in the Seattle area. About 200,000 homes were without power in the Greater Seattle area after the storm.

The January 2010 North American winter storms were a group of seven powerful winter storms that affected Canada and the Contiguous United States, particularly California. The storms developed from the combination of a strong El Niño episode, a powerful jet stream, and an atmospheric river that opened from the West Pacific Ocean into the Western Seaboard. The storms shattered multiple records across the Western United States, with the sixth storm breaking records for the lowest recorded air pressure in multiple parts of California, which was also the most powerful winter storm to strike the Southwestern United States in 140 years. The fourth, fifth, and sixth storms spawned several tornadoes across California, with at least 6 tornadoes confirmed in California ; the storms also spawned multiple waterspouts off the coast of California. The storms dumped record amounts of rain and snow in the Western United States, and also brought hurricane-force winds to the U.S. West Coast, causing flooding and wind damage, as well as triggering blackouts across California that cut the power to more than 1.3 million customers. The storms killed at least 10 people, and caused more than $66.879 million in damages.

The March 2014 North American winter storm, also unofficially referred to as Winter Storm Titan, was an extremely powerful winter storm that affected much of the United States and portions of Canada. It was one of the most severe winter storms of the 2013–14 North American winter storm season, storm affecting most of the Western Seaboard, and various parts of the Eastern United States, bringing damaging winds, flash floods, and blizzard and icy conditions.

The 2013–14 North American winter was one of the most significant for the United States, due in part to the breakdown of the polar vortex in November 2013, which allowed very cold air to travel down into the United States, leading to an extended period of very cold temperatures. The pattern continued mostly uninterrupted throughout the winter and numerous significant winter storms affected the Eastern United States, with the most notable one being a powerful winter storm that dumped ice and snow in the Southeastern United States and the Northeastern United States in mid-February. Most of the cold weather abated by the end of March, though a few winter storms did affect the Western United States towards the end of the winter.

The December 2014 North American storm complex was a powerful winter storm that impacted the West Coast of the United States, beginning on the night of December 10, 2014, resulting in snow, wind, and flood watches. Fueled by the Pineapple Express, an atmospheric river originating in the tropical waters of the Pacific Ocean adjacent to the Hawaiian Islands, the storm was the strongest to affect California since January 2010. The system was also the single most intense storm to impact the West Coast, in terms of minimum low pressure, since a powerful winter storm in January 2008. The National Weather Service classified the storm as a significant threat, and issued 15 warnings and advisories, including a Blizzard Warning for the Northern Sierra Nevada.

The 2011–12 North American winter by and large saw above normal average temperatures across the continent, with the Contiguous United States encountering its fourth-warmest winter on record, along with an unusually low number of significant winter precipitation events. The primary outlier was Alaska, parts of which experienced their coldest January on record.

The 2010–11 North American winter was influenced by an ongoing La Niña, seeing winter storms and very cold temperatures affect a large portion of the Continental United States, even as far south as the Texas Panhandle. Notable events included a major blizzard that struck the Northeastern United States in late December with up to 2 feet (24 in) of snowfall and a significant tornado outbreak on New Year's Eve in the Southern United States. By far the most notable event was a historic blizzard that impacted areas from Oklahoma to Michigan in early February. The blizzard broke numerous snowfall records, and was one of the few winter storms to rank as a Category 5 on the Regional Snowfall Index. In addition, Oklahoma set a statewide low temperature record in February.

Tropical Storm Imelda was a tropical cyclone which was the fourth-wettest storm on record in the U.S. state of Texas, causing devastating and record-breaking floods in southeast Texas. The eleventh tropical cyclone and ninth named storm of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season, Imelda formed out of an upper-level low that developed in the Gulf of Mexico and moved westward. Little development occurred until the system was near the Texas coastline, where it rapidly developed into a tropical storm before moving ashore shortly afterward on September 17. Imelda weakened after landfall, but continued bringing large amounts of flooding rain to Texas and Louisiana, before dissipating on September 21.

Hurricane Genevieve was a strong tropical cyclone that almost made landfall on the Baja California Peninsula in August 2020. Genevieve was the twelfth tropical cyclone, seventh named storm, third hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2020 Pacific hurricane season. The cyclone formed from a tropical wave that the National Hurricane Center (NHC) first started monitoring on August 10. The wave merged with a trough of low pressure on August 13, and favorable conditions allowed the wave to intensify into Tropical Depression Twelve-E at 15:00 UTC. Just six hours later, the depression became a tropical storm and was given the name Genevieve. Genevieve quickly became a hurricane by August 17, and Genevieve began explosive intensification the next day. By 12:00 UTC on August 18, Genevieve reached its peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 130 mph and a minimum central pressure of 950 millibars (28 inHg). Genevieve began to weaken on the next day, possibly due to cooler waters caused by Hurricane Elida earlier that month. Genevieve weakened below tropical storm status around 18:00 UTC on August 20, as it passed close to Baja California Sur. Soon afterward, Genevieve began to lose its deep convection and became a post-tropical cyclone by 21:00 UTC on August 21, eventually dissipating off the coast of Southern California late on August 24.

The December 5–6, 2020 nor'easter brought heavy snowfall, hurricane-force wind gusts, blizzard conditions, and coastal flooding to much of New England in the first few days of December 2020. The system originated on the Mid-Atlantic coast late on December 4. It then moved up the East Coast of the United States from December 5–6, bombing out and bringing heavy wet snow to the New England states. It brought up to 18 inches (46 cm) of snow in northern New England, with widespread totals of 6–12 inches (15–30 cm) farther south.

The January 31 – February 3, 2021 nor'easter, also known as the 2021 Groundhog Day nor'easter, was a powerful, severe, and erratic nor'easter that impacted much of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada from February 1–3 with heavy snowfall, blizzard conditions, strong gusty winds, storm surge, and coastal flooding. The storm first developed as an extratropical cyclone off the West Coast of the United States on January 25, with the storm sending a powerful atmospheric river into West Coast states such as California, where very heavy rainfall, snowfall, and strong wind gusts were recorded, causing several hundred thousand power outages and numerous mudslides. The system moved ashore several days later, moving into the Midwest and dropping several inches of snow across the region. On February 1, the system developed into a nor'easter off the coast of the Northeastern U.S., bringing prolific amounts of snowfall to the region. Large metropolitan areas such as Boston and New York City saw as much as 18–24 inches (46–61 cm) of snow accumulations from January 31 to February 2, making it the worst snowstorm to affect the megalopolis since the January 2016 blizzard. It was given the unofficial name Winter Storm Orlena by The Weather Channel.

The February 15–20, 2021 North American winter storm, also unofficially referred to as Winter Storm Viola, or to some as simply The North Texas Freeze, was a significant and widespread snow and ice storm across much of the United States, Northern Mexico, and Southern Canada. The system started out as a winter storm on the West Coast of the United States on February 15, later moving southeast into the Southern Plains and Deep South from February 16–17. It then moved into the Appalachian Mountains and Northeastern United States, before finally moving out to sea on February 20. The storm subsequently became a powerful low pressure system over the North Atlantic, before eventually dissipating on February 26.

The March 2021 North American blizzard was a record-breaking blizzard in the Rocky Mountains and a significant snowstorm in the Upper Midwest that occurred in mid-March 2021. It brought Cheyenne, Wyoming their largest two-day snowfall on record, and Denver, Colorado their second-largest March snowfall on record. The storm originated from an extratropical cyclone in the northern Pacific Ocean in early March, arriving on the west coast of the United States by March 10. The storm moved into the Rocky Mountains on Saturday, March 13, dumping up to 2–3 feet (61–91 cm) of snow in some areas. It was unofficially given the name Winter Storm Xylia.

The April 2021 nor'easter, also referred to as the 2021 Spring nor'easter, was a significant late-season nor'easter that impacted much of New England with heavy snowfall, gusty winds, thundersnow, and near-whiteout conditions from April 15–17, 2021. The system originated from a weak frontal system late on April 14 over North Carolina, which moved into the ocean the next day and began to strengthen. The low-pressure steadily deepened as it moved up the East Coast, and developed an eye-like feature just prior to peak intensity. It prompted a fairly large area of Winter Storm Warnings across interior sections of New England, with Winter Weather Advisories being issued closer to the coast. Over 20,000 customers lost power at the height of the storm on April 16 due to heavy wet snow, and near-whiteout conditions were reported in many areas. Several injuries, some serious, occurred as well, mostly due to traffic incidents on poorly-treated roadways during the storm. Damage estimates from the system are currently not calculated.

The January 2022 North American blizzard caused widespread and disruptive impacts to the Atlantic coast of North America from northern Delaware to Nova Scotia with as much as 2.5 feet (30 in) of snowfall, blizzard conditions and coastal flooding at the end of January 2022. Forming from the energy of a strong mid- to upper-level trough, the system developed into a low-pressure area off the Southeast United States on January 28. The system then quickly intensified that night as it traveled northeast parallel to the coast on January 29, bringing heavy snowfall blown by high winds to the upper East Coast of the continent. Further north, it also moved inland in Maine and its width meant it strongly impacted all three of Canada's Maritime provinces. In some areas, mainly the coastal regions due to the wind, areas of New Jersey, Long Island and Massachusetts, it was the first blizzard since a storm in January 2018. The storm was considered a "bomb cyclone" as it rapidly intensified and barometric pressure dropped at least 24 millibars over a 24-hour period. The storm was given names such as Blizzard of 2022 and Winter Storm Kenan.

Tropical Storm Pulasan, known in the Philippines as Tropical Storm Helen, was a tropical cyclone that impacted East China, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines in September 2024. Pulasan developed over the Philippine Sea as a tropical depression on September 15 and strengthened into the fourteenth named storm of the annual typhoon season the following day. After gaining organization, the system rapidly developed and reached its peak intensity with winds of 85 km/h and a central pressure of 992 hPa (29.29 inHg). Pulasan then turned northwestward, eventually moving across Okinawa Island and making landfall in Zhoushan, Zhejiang, followed by a second landfall in Shanghai, just days after Typhoon Bebinca affected the Shanghai area on September 19. Pulasan reemerged over the East China Sea, just off the coast of China. By September 21, Pulasan had transitioned into an extratropical low as it moved east-northeastward and became embedded within the polar front jet to the north, passing over southern South Korea. The extratropical storm entered the Sea of Japan on September 22, crossed the Tōhoku region, and then emerged into the Pacific Ocean while being absorbed by another extratropical cyclone. The extratropical remnants of Pulasan were last noted by the Japan Meteorological Agency on September 24 near the International Dateline; however, the Ocean Prediction Center indicated that these remnants crossed the International Dateline and entered the Central North Pacific Ocean late on September 25. Afterward, the remnants gradually approached the coast of British Columbia, making landfall on September 27 and dissipating after moving inland the same day.

The 2024–25 North American winter is the current winter season that is ongoing across the continent of North America. The most notable events of the season so far have included a powerful bomb cyclone that impacted the West Coast of the United States in mid-to-late November, as well as a severe lake-effect snowstorm in the Great Lakes later that month. Additional events included a a wide-ranging blizzard that affected much of the central parts of the United States in early January, followed by a a winter storm that brought snow and ice to the South, a quick-moving nor'easter that affected much of the Northeastern United States, and a historic blizzard that struck the Gulf Coast of the United States in late January. A severe cold wave also brought extremely cold temperatures to the majority of the continent throughout much of January, the coldest such January in many years. An ongoing weak La Niña is expected to influence the weather patterns across the North American continent this winter. Collectively, the winter weather events so far have resulted in approximately 23 deaths and at least US$500 million in damages.