Split

Hopi interaction with outsiders slowly increased during 1850–1860 due to missionaries, traders, and surveyors for the US government. Contact remained sporadic and informal until 1870 when an Indian agent was appointed to the Hopi, followed by the establishment of the Hopi Indian Agency in Keams Canyon in 1874.

Interaction with the US government increased with the establishment of the Hopi Reservation in 1882. This led to a number of changes for the Hopi way of life. Missionary efforts intensified and Hopi children were kidnapped from their homes and forced to attend school, exposing them to new cultural influences. [8]

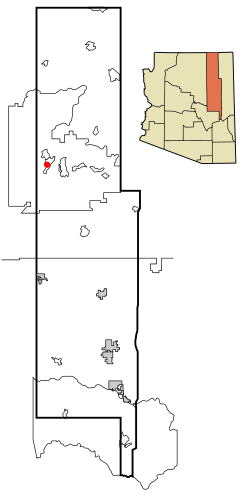

In 1890 a number of residents more receptive to the cultural influences moved closer to the trading post to establish Kykotsmovi Village, sometimes called New Oraibi. The continuing tension caused by the ideological schism between the "friendlies" ("New Hopi" to the traditional Hopi), those who were open to these cultural influences, and the "hostiles" (or "Traditionalists" led by Yukiuma) who opposed them (those who desired to preserve Hopi ways) [9] led to an event called the "Oraibi Split" in 1906. Tribal leaders on differing sides of the schism engaged in a bloodless competition to determine the outcome, [10] which resulted in the expulsion of the hostiles (traditionalists), who left to found the village of Hotevilla. Subsequent efforts by the displaced residents to reintegrate resulted in an additional split, with the second group founding Bacavi.

With the loss of much of its population, Oraibi lost its place as the center of Hopi culture. Although the Hopi tribal constitution, maneuvered into being by the coal mining interests in 1939, provides each village with a seat on the tribal council, Hotevilla, where most of the traditional Hopi settled, has declined to elect a representative and maintains independence from the tribal council. Kykotsmovi Village is now the seat of the Hopi tribal government.