The Lecanoraceae are a family of lichenized fungi in the order Lecanorales. Species of this family have a widespread distribution.

Gloeoheppiaceae is a family of ascomycete fungi in the order Lichinales. The family contains ten species distributed amongst three genera. Most species are lichenised with cyanobacteria. Species in this family are mostly found in desert areas. Modern molecular phylogenetics analysis casts doubt on the phylogenetic validity of the family, suggesting a more appropriate placement of its species in the family Lichinaceae.

The Baeomycetales are an order of mostly lichen-forming fungi in the subclass Ostropomycetidae, in the class Lecanoromycetes. It contains 8 families, 33 genera and about 170 species. As a result of molecular phylogenetics research published in the late 2010s, several orders were folded into the Baeomycetales, resulting in a substantial increase in the number of taxa.

Stirtoniella is a lichen genus in the family Ramalinaceae. It is a monotypic genus, containing the single species Stirtoniella kelica, a crustose and corticolous lichen originally described from New Zealand in 1873 as a species of Lecidea. The photobiont is an alga of the family Chlorococcaceae. The genus is named after Scottish mycologist James Stirton.

Malcolmiella is a genus of lichenized fungi in the family Pilocarpaceae.

Lecidella is a genus of crustose lichens in the family Lecanoraceae.

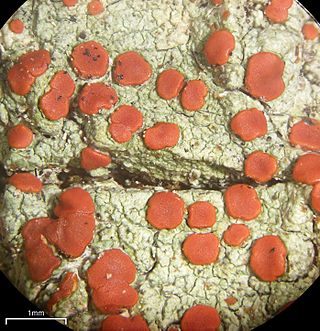

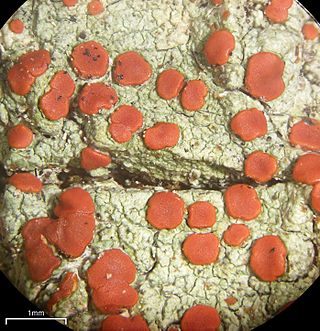

Ramboldia is a genus of lichen-forming fungi in the family Ramboldiaceae. The genus was circumscribed in 1994 by Gintaras Kantvilas and John Alan Elix. It was emended in 2008 by the inclusion of Pyrrhospora species containing the anthraquinone russulone in their apothecia and having a prosoplectenchymatous exciple. The family Ramboldiaceae was circumscribed in 2014 to contain the genus.

Porpidia is a genus of crustose lichens in the family Lecideaceae.

Rhizocarpon is a genus of crustose, saxicolous, lecideoid lichens in the family Rhizocarpaceae. The genus is common in arctic-alpine environments, but also occurs throughout temperate, subtropical, and even tropical regions. They are commonly known as map lichens because of the prothallus forming border-like bands between colonies in some species, like the common map lichen.

Fuscidea is a genus of crustose lichens in the family Fuscideaceae. It has about 40 species. The genus was circumscribed in 1972 by lichenologists Volkmar Wirth and Antonín Vězda, with Fuscidea aggregatilis assigned as the type species.

Hypocenomyce is a genus of lichen-forming fungi in the family Ophioparmaceae. Species in the genus grow on bark and on wood, especially on burned tree stumps and trunks in coniferous forest. Hypocenomyce lichens are widely distributed in the northern hemisphere.

Malmideaceae is a family of crustose and corticolous lichens in the order Lecanorales. It contains eight genera and about 70 species.

Varicellaria is a genus of crustose lichens. It is the only genus in the family Varicellariaceae.

Rhizocarpales are an order of lichen-forming fungi in the subclass Lecanoromycetidae of the class Lecanoromycetes. It has two families, Rhizocarpaceae and Sporastatiaceae, which contain mostly crustose lichens.

Strangospora is a genus of lichen-forming fungi. It is the only genus in the family Strangosporaceae, which itself is of uncertain taxonomic placement in the Ascomycota. It contains 10 species.

Schaereria fuscocinerea is a species of saxicolous (rock-dwelling), crustose lichen in the family Schaereriaceae. It was first formally described in 1852 by Finnish lichenologist William Nylander, as Lecidea fusco-cinerea. Georges Clauzade and Claude Roux transferred it to the genus Schaereria in 1985. The species has a cosmopolitan distribution and is found in both northern and southern hemispheres, where it grows on hard siliceous rocks, often in arctic and mountainous areas. Similar species include Lambiella gyrizans and L. mullensis, which can be distinguished from Schaereria fuscocinerea by microscopic and chemical characteristics.

Schaereria serenior is a species of saxicolous (bark-dwelling), crustose lichen in the family Schaereriaceae. Found in Finland, it was first formally described as a new species by the Finnish lichenologist Edvard August Vainio, who classified it as a variety of the species Lecidea tenebrosa. Auguste-Marie Hue promoted it to distinct species status in 1913 as Lecidea serenior. Alexander Zahlbruckner proposed to transfer it to the genus Caloplaca in 1931. Most recently, Orvo Vitikainen transferred it to Schaereria in 2004, a few years after that genus had been resurrected from a long period of disuse. It is one of two species of Schaereria found in Finland; the other is S. parasemella.

Schaereria parasemella is a species of saxicolous (rock-dwelling), crustose lichen in the family Schaereriaceae. It is lichenicolous, meaning it grows on other lichens; its host species is Biatora vernalis. It has been recorded from Alaska, Greenland, Scandinavia, France, and Russia.