Related Research Articles

In grammar, tense is a category that expresses time reference. Tenses are usually manifested by the use of specific forms of verbs, particularly in their conjugation patterns.

The Xavante language is an Akuwẽ language spoken by the Xavante people in the area surrounding Eastern Mato Grosso, Brazil. The Xavante language is unusual in its phonology, its ergative object–agent–verb word order, and its use of honorary and endearment terms in its morphology.

The Japanese language has a system of honorific speech, referred to as keigo, parts of speech that show respect. Their use is mandatory in many social situations. Honorifics in Japanese may be used to emphasize social distance or disparity in rank, or to emphasize social intimacy or similarity in rank. Japanese honorific titles, often simply called honorifics, consist of suffixes and prefixes when referring to others in a conversation.

In linguistics, a causative is a valency-increasing operation that indicates that a subject either causes someone or something else to do or be something or causes a change in state of a non-volitional event. Normally, it brings in a new argument, A, into a transitive clause, with the original subject S becoming the object O.

An augmentative is a morphological form of a word which expresses greater intensity, often in size but also in other attributes. It is the opposite of a diminutive.

Vaeakau-Taumako is a Polynesian language spoken in some of the Reef Islands as well as in the Taumako Islands in the Temotu province of the Solomon Islands.

Tuscarora, sometimes called Skarò˙rə̨ˀ, was the Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people, spoken in southern Ontario, Canada, North Carolina and northwestern New York around Niagara Falls, in the United States, before becoming extinct in late 2020. The historic homeland of the Tuscarora was in eastern North Carolina, in and around the Goldsboro, Kinston, and Smithfield areas.

The Natchez language is the ancestral language of the Natchez people who historically inhabited Mississippi and Louisiana, and who now mostly live among the Muscogee and Cherokee peoples in Oklahoma. The language is considered to be either unrelated to other indigenous languages of the Americas or distantly related to the Muskogean languages.

The grammar of Classical Nahuatl is agglutinative, head-marking, and makes extensive use of compounding, noun incorporation and derivation. That is, it can add many different prefixes and suffixes to a root until very long words are formed. Very long verbal forms or nouns created by incorporation, and accumulation of prefixes are common in literary works. New words can thus be easily created.

Tariana is an endangered Maipurean language spoken along the Vaupés River in Amazonas, Brazil by approximately 100 people. Another approximately 1,500 people in the upper and middle Vaupés River area identify themselves as ethnic Tariana but do not speak the language fluently.

Máku, also spelled Mako, and in the language itself Jukude, is an unclassified language and likely language isolate once spoken on the Brazil–Venezuela border in Roraima along the upper Uraricoera and lower Auari rivers, west of Boa Vista, by the Jukudeitse. 300 years ago, the Jukude territory was between the Padamo and Cunucunuma rivers to the southwest.

The Ojibwe language is an Algonquian American Indian language spoken throughout the Great Lakes region and westward onto the northern plains. It is one of the largest American Indian languages north of Mexico in terms of number of speakers, and exhibits a large number of divergent dialects. For the most part, this article describes the Minnesota variety of the Southwestern dialect. The orthography used is the Fiero Double-Vowel System.

In linguistics, coordination is a complex syntactic structure that links together two or more elements; these elements are called conjuncts or conjoins. The presence of coordination is often signaled by the appearance of a coordinator, e.g. and, or, but. The totality of coordinator(s) and conjuncts forming an instance of coordination is called a coordinate structure. The unique properties of coordinate structures have motivated theoretical syntax to draw a broad distinction between coordination and subordination. It is also one of the many constituency tests in linguistics. Coordination is one of the most studied fields in theoretical syntax, but despite decades of intensive examination, theoretical accounts differ significantly and there is no consensus on the best analysis.

Wagiman, also spelt Wageman, Wakiman, Wogeman, and other variants, is a near-extinct Aboriginal Australian language spoken by a small number of Wagiman people in and around Pine Creek, in the Katherine Region of the Northern Territory.

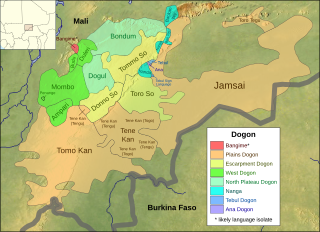

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is an endangered Algonquian language spoken by the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples along both sides of the border between Maine in the United States and New Brunswick, Canada. The language consists of two major dialects: Maliseet, which is mainly spoken in the Saint John River Valley in New Brunswick; and Passamaquoddy, spoken mostly in the St. Croix River Valley of eastern Maine. However, the two dialects differ only slightly, mainly in their phonology. The indigenous people widely spoke Maliseet-Passamaquoddy in these areas until around the post-World War II era when changes in the education system and increased marriage outside of the speech community caused a large decrease in the number of children who learned or regularly used the language. As a result, in both Canada and the U.S. today, there are only 600 speakers of both dialects, and most speakers are older adults. Although the majority of younger people cannot speak the language, there is growing interest in teaching the language in community classes and in some schools.

In linguistics, an honorific is a grammatical or morphosyntactic form that encodes the relative social status of the participants of the conversation. Distinct from honorific titles, linguistic honorifics convey formality FORM, social distance, politeness POL, humility HBL, deference, or respect through the choice of an alternate form such as an affix, clitic, grammatical case, change in person or number, or an entirely different lexical item. A key feature of an honorific system is that one can convey the same message in both honorific and familiar forms—i.e., it is possible to say something like "The soup is hot" in a way that confers honor or deference on one of the participants of the conversation.

In linguistics, grammatical mood is a grammatical feature of verbs, used for signaling modality. That is, it is the use of verbal inflections that allow speakers to express their attitude toward what they are saying. The term is also used more broadly to describe the syntactic expression of modality – that is, the use of verb phrases that do not involve inflection of the verb itself.

Yolmo (Hyolmo) or Helambu Sherpa, is a Tibeto-Burman language of the Hyolmo people of Nepal. Yolmo is spoken predominantly in the Helambu and Melamchi valleys in northern Nuwakot District and northwestern Sindhupalchowk District. Dialects are also spoken by smaller populations in Lamjung District and Ilam District and also in Ramecchap District. It is very similar to Kyirong Tibetan and less similar to Standard Tibetan and Sherpa. There are approximately 10,000 Yolmo speakers, although some dialects have larger populations than others.

The system of Russian forms of addressing is used by the speakers of Russian languages to linguistically encode relative social status, degree of respect and the nature of interpersonal relationship. Typical linguistic tools employed for this purpose include using different parts of a person's full name, name suffixes, and honorific plural.