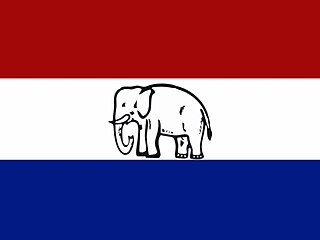

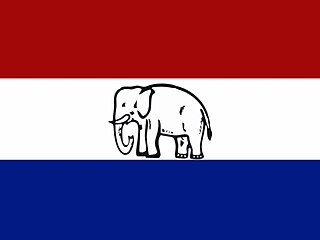

Asom Gana Parishad is a political party in the state of Assam, India. The AGP was formed following the historic Assam Accord of 1985 and formally launched at the Golaghat Convention held from 13 to 14 October 1985 in Golaghat, which also allowed Prafulla Kumar Mahanta who was the youngest chief minister of the state to be elected. The AGP has formed government twice once in 1985 then again in 1996. The popularity of AGP surged in the late 1980s but declined in the 2000s. After a 20-year gap, AGP, in alliance with NDA, won a Lok Sabha seat in 2024.

The Assam Movement (1979–1985) was a popular uprising in Assam, India, that demanded the Government of India detect, disenfranchise and deport illegal aliens. Led by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) the movement defined a six-year period of sustained civil disobedience campaigns, political instability and widespread ethnic violence. The movement ended in 1985 with the Assam Accord.

All Assam Students' Union or AASU is an Assamese nationalist student's organization in Assam, India. It is best known for leading the six-year Assam Movement against Bengalis of both Indian and Bangladeshi origin living in Assam. The original leadership of the organisation, after the historic Assam Accord of 1985, became part of the newly formed Asom Gana Parishad which formed a state government in Assam.

Sarbananda Sonowal is an Indian politician who has served as Minister of Ports, Shipping and Waterways since 2021. He also has been the Member of the Rajya Sabha representing Assam since 2021 and also a member of the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs since 2021. He previously served as the 14th Chief Minister of Assam from 2016 to 2021 and as a member of Assam Legislative Assembly for Majuli from 2016 to 2021 and for Moran from 2001 to 2004. Sonowal earlier served as the Assam state unit President of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) from 2012 to 2014 and again from 2015 to 2016. He also served as the Minister of Sports and Youth Affairs, Government of India, from 2014 to 2016 and the Minister of State for Entrepreneurship and Skill Development from 2014 to 2014 and the member of the Lok Sabha from Lakhimpur from 2014 to 2016 and from Dibrugarh from 2004 to 2009. He was also the member of the Asom Gana Parishad from 2001 to 2011.

Ram D. Pradhan was an Indian Administrative Service officer, from the 1952 batch who served as Union Home Secretary and Governor of Arunachal Pradesh during the Rajiv Gandhi government.

The Assamese people are a socio-ethnic linguistic identity that has been described at various times as nationalistic or micro-nationalistic. This group is often associated with the Assamese language, the easternmost Indo-Aryan language, and Assamese people mostly live in the Brahmaputra Valley region of Assam, where they are native and constitute around 56% of the Valley's population. The use of the term precedes the name of the language or the people. It has also been used retrospectively to the people of Assam before the term "Assamese" came into use. They are an ethnically diverse group formed after centuries of assimilation of Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Indo-Aryan and Tai populations, and constitute a tribal-caste continuum—though not all Assamese people are Hindus and ethnic Assamese Muslims numbering around 42 lakh (4,200,000) constitute a significant part of this identity. The total population of Assamese speakers in Assam is nearly 15.09 million which makes up 48.38% of the population of state according to the Language census of 2011.

The Nellie massacre took place in central Assam during a six-hour period on the morning of 18 February 1983. The massacre claimed the lives of 1,600–2,000 people from 14 villages—Alisingha, Khulapathar, Basundhari, Bugduba Beel, Bugduba Habi, Borjola, Butuni, Dongabori, Indurmari, Mati Parbat, Muladhari, Mati Parbat no. 8, Silbheta, Borburi and Nellie—of Nagaon district. The victims were illegal migrants of Bengali Muslim descent. Three media personnel—Hemendra Narayan of The Indian Express, Bedabrata Lahkar of The Assam Tribune, and Sharma of ABC—were witnesses.

Hiteswar Saikia was an Indian politician who served as the 10th chief minister of Assam for two terms, firstly from 28 February 1983 to 23 December 1985 and then from 30 June 1991 to 22 April 1996. He was the 1st Governor of Mizoram from 1987 to 1989 and the 6th Lieutenant Governor of Mizoram from 1986 to 1987. He was the education minister in the Government of Assam from and from 1980 to 1981 and again from 1982 to 1982. He was the Minister of State for Home, Education And public relations from 1972 to 1974 and the minister of Home from 1974 to 1978. He represented the Nazira constituency in the Assam Legislative Assembly from 1972 to 1988 and again from 1991 to 1996.

Anup Chetia is the General Secretary of the banned United Liberation Front of Assam in Assam. He is also one of the founder leaders of the group. He was born at Jerai Gaon in Tinsukia district of Assam.

Bangladeshis in India are members of the Bangladesh diaspora who currently reside in India. The mass migration into India since Bangladesh independence has led to the creation of anti-foreigner movements, instances of mass violence and political tension between Bangladesh and India, but it has also created measurable economic benefits for both nations.

Assam has a rich and complex history of Islam that dates back over 700 years. After the earlier Burmese Muslims and Sindhi or Indian Muslims converted to Islam, after them Assam has significant place on earlier conversion. The majority of Muslims in Assam are associated with the traditional culture and society of Akhand Bharat or Greater India, with about 10.67% of the population identifying as Muslim, the second largest religion in the Republic of India. There are two main types of Islam in Assam: Shia Islam, practiced by about 1.5% of Muslims, and Sunni Islam, a mix of traditional and modern followers, practiced by about 98.5% of Muslims. Sunni Muslims in Assam include various groups, such as Bengali Muslims, Kabuli Muslims, Bihari Muslims, Uttar Pradesh Muslims, Manipuri Muslims, Ahom Muslims, and All Indian Caste Muslims. Some of these groups are affiliated and representatives of multiparty movements like Nadwatul Ulama, Deobandi '(through many organizations)', Jamiat, Tablighi Jamaat and many of other related parties. There are also some Muslims who are not religious believers or followers (non-practicing).. Muslims live in a total of Fifteen districts in the state of Assam.

The National Register of Citizens for Assam is a registry (NRC) meant to be maintained by the Government of India for the state of Assam. It is expected to contain the names and certain relevant information for the identification of genuine Indian citizens in the state. The register for Assam was first prepared after the 1951 Census of India. Since then it was not updated until the major "updation exercise" conducted during 2013–2019, which caused numerous difficulties. In 2019, the government also declared its intention of creating such a registry for the whole of India, leading to major protests all over the country.

Biraj Kumar Sarma was an Asom Gana Parishad politician from Assam. He was born 1948. He was popularly referred to as " the people's leader".[6]

The Golaghat Convention was a historic national convention of the people of Assam, organised in Golaghat for 2 days from 13–14 October 1985.

The 8th Assam Legislative Assembly election was held in two phases in 1985 to elect members from 126 constituencies in Assam, India.

All Assam Minorities Students' Union (AAMSU) is a student organization from the religious and linguistic minorities communities of Assam. It was formed in 1980, on the eve of Assam movement, to safeguard the interest of the minorities social rights and their strangle and held rallies in Barpeta c and shouting slogs of jay Aay Asom. It claims fighting for the minorities people facing prosecution at the hands of government.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003 was passed by the Parliament of India in December 2003, and received presidential assent in January 2004. It is labelled "Act 6 of 2004".

Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty is an Indian journalist and writer from the state of Assam, based in the city of New Delhi. Currently the National Affairs Editor with the digital news publication The Wire, she was formerly a special correspondent of the English language national newspaper The Hindu. She has been the subject of widespread critical acclaim for the documentation on the Assam Movement, the Assam Accord and the insurgencies in Assam in her debut book Assam: The Accord, The Discord.

Operation Bajrang was a military operation, conducted by the Indian army, in Assam, against the militant organization, United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA).