Multimedia refers to the integration of multiple forms of content such as text, audio, images, video, and interactive elements into a single digital platform or application. This integration allows for a more immersive and engaging experience compared to traditional single-medium content. Multimedia is utilized in various fields including education, entertainment, communication, game design, and digital art, reflecting its broad impact on modern technology and media.

Speech synthesis is the artificial production of human speech. A computer system used for this purpose is called a speech synthesizer, and can be implemented in software or hardware products. A text-to-speech (TTS) system converts normal language text into speech; other systems render symbolic linguistic representations like phonetic transcriptions into speech. The reverse process is speech recognition.

Computer accessibility refers to the accessibility of a computer system to all people, regardless of disability type or severity of impairment. The term accessibility is most often used in reference to specialized hardware or software, or a combination of both, designed to enable the use of a computer by a person with a disability or impairment.

A screen reader is a form of assistive technology (AT) that renders text and image content as speech or braille output. Screen readers are essential to people who are blind, and are useful to people who are visually impaired, illiterate, or have a learning disability. Screen readers are software applications that attempt to convey what people with normal eyesight see on a display to their users via non-visual means, like text-to-speech, sound icons, or a braille device. They do this by applying a wide variety of techniques that include, for example, interacting with dedicated accessibility APIs, using various operating system features, and employing hooking techniques.

Video game design is the process of designing the rules and content of video games in the pre-production stage and designing the gameplay, environment, storyline and characters in the production stage. Some common video game design subdisciplines are world design, level design, system design, content design, and user interface design. Within the video game industry, video game design is usually just referred to as "game design", which is a more general term elsewhere.

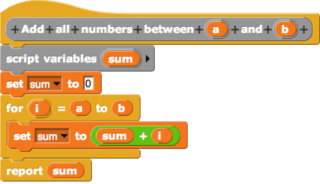

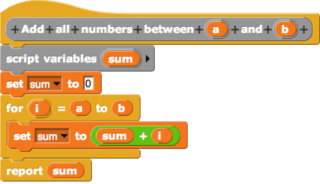

In computing, a visual programming language, also known as diagrammatic programming, graphical programming or block coding, is a programming language that lets users create programs by manipulating program elements graphically rather than by specifying them textually. A VPL allows programming with visual expressions, spatial arrangements of text and graphic symbols, used either as elements of syntax or secondary notation. For example, many VPLs are based on the idea of "boxes and arrows", where boxes or other screen objects are treated as entities, connected by arrows, lines or arcs which represent relations. VPLs are generally the basis of Low-code development platforms.

A music video game, also commonly known as a music game, is a video game where the gameplay is meaningfully and often almost entirely oriented around the player's interactions with a musical score or individual songs. Music video games may take a variety of forms and are often grouped with puzzle games due to their common use of "rhythmically generated puzzles".

In human–computer interaction, WIMP stands for "windows, icons, menus, pointer", denoting a style of interaction using these elements of the user interface. Other expansions are sometimes used, such as substituting "mouse" and "mice" for menus, or "pull-down menu" and "pointing" for pointer.

An electronic game is a game that uses electronics to create an interactive system with which a player can play. Video games are the most common form today, and for this reason the two terms are often used interchangeably. There are other common forms of electronic games, including handheld electronic games, standalone arcade game systems, and exclusively non-visual products.

A voice-user interface (VUI) enables spoken human interaction with computers, using speech recognition to understand spoken commands and answer questions, and typically text to speech to play a reply. A voice command device is a device controlled with a voice user interface.

Tactile graphics, including tactile pictures, tactile diagrams, tactile maps, and tactile graphs, are images that use raised surfaces so that a visually impaired person can feel them. They are used to convey non-textual information such as maps, paintings, graphs and diagrams.

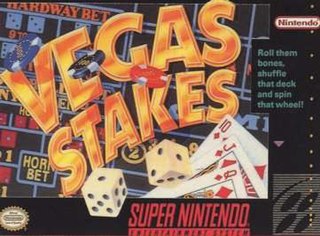

Vegas Stakes, known as Las Vegas Dream in Japan, is a 1993 gambling video game developed by HAL Laboratory and published by Nintendo for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. It was released in North America in April 1993, in Europe the same year and in Japan by Imagineer in September 1993. A port for the Game Boy was released only in North America in December 1995. The Super NES version supports the Super NES Mouse, while the Game Boy version is compatible with the Super Game Boy, and features borders which use artwork from the Super NES version. It is the sequel to the NES game Vegas Dream.

Since the Global Positioning System (GPS) was introduced in the late 1980s there have been many attempts to integrate it into a navigation-assistance system for blind and visually impaired people.

Within the field of human–computer interaction, accessibility of video games is considered a sub-field of computer accessibility, which studies how software and computers can be made accessible to users with various types of impairments. It can also include tabletop RPGs, board games, and related products.

Real Sound: Kaze no Regret, is an adventure audio game developed and published by Warp. The game was first released for the Saturn in July 1997, and later for the Dreamcast in March 1999. Real Sound was intended to provide equal access to sighted and blind players. The subtitle Kaze no Regret means "The wind's regret" or "The Wind(s) of Regret".

An adventure game is a video game genre in which the player assumes the role of a protagonist in an interactive story, driven by exploration and/or puzzle-solving. The genre's focus on story allows it to draw heavily from other narrative-based media, such as literature and film, encompassing a wide variety of genres. Most adventure games are designed for a single player, since the emphasis on story and character makes multiplayer design difficult. Colossal Cave Adventure is identified by Rick Adams as the first such adventure game, first released in 1976, while other notable adventure game series include Zork, King's Quest, Monkey Island, Syberia, and Myst.

Text to speech in digital television refers to digital television products that use speech synthesis to enable access to blind or partially sighted people. By combining a digital television with a speech synthesis engine, blind and partially sighted people are able to access information that is normally displayed visually in order to operate the menus and electronic program guides of the receiver.

Alternative formats include audio, braille, electronic or large print versions of standard print such as educational material, textbooks, information leaflets, and even people's personal bills and letters. Alternative formats are created to help people who are blind or visually impaired to gain access to information either by sight, by hearing (audio) or by touch (braille).

A cutscene or event scene is a sequence in a video game that is not interactive, interrupting the gameplay. Such scenes are used to show conversations between characters, set the mood, reward the player, introduce newer models and gameplay elements, show the effects of a player's actions, create emotional connections, improve pacing or foreshadow future events.

The Vale: Shadow of the Crown is a 2021 action role-playing game developed by Falling Squirrel. Players control a blind princess. The game has few visuals and is almost entirely an audio game.