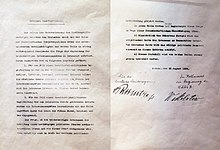

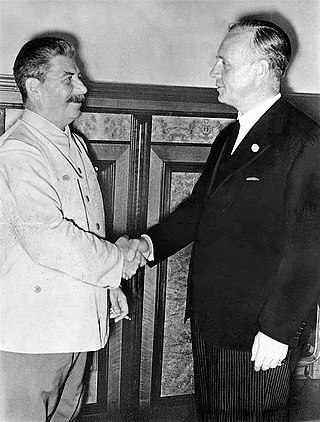

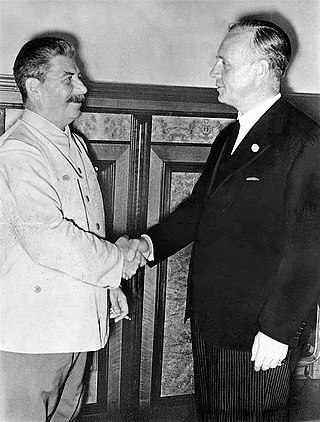

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, with a secret protocol establishing Soviet and German spheres of influence across Eastern Europe. The pact was signed in Moscow on 24 August 1939 by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.

The Singing Revolution was a series of events from 1987 to 1991 that led to the restoration of independence of the three Soviet-occupied Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania at the end of the Cold War. The term was coined by an Estonian activist and artist, Heinz Valk, in an article published a week after the 10–11 June 1988 spontaneous mass evening singing demonstrations at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds.

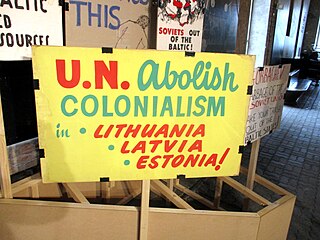

The occupation of the Baltic states was a period of annexation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by the Soviet Union from 1940 until its dissolution in 1991. For a brief period, Nazi Germany occupied the Baltic states after it invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

The Sąjūdis, initially known as the Reform Movement of Lithuania, is a political organisation which led the struggle for Lithuanian independence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was established on 3 June 1988 as the first opposition party in Soviet Lithuania, and was led by Vytautas Landsbergis. Its goal was to seek the return of independent status for Lithuania.

The Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania or Act of 11 March was an independence declaration by Lithuania adopted on 11 March 1990, signed by all members of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania led by Sąjūdis. The act emphasized restoration and legal continuity of the interwar-period Lithuania, which was occupied by the Soviet Union and annexed in June 1940. In March 1990, it was the first of the 15 Soviet republics to declare independence, with the rest following to continue for 21 months, concluding with Kazakhstan's independence in 1991. These events led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991.

The three Baltic countries, or the Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – are held to have continued as independent states under international law while under Soviet occupation from 1940 to 1991, as well as during the German occupation in 1941–1944/1945. The prevailing opinion accepts the Baltic thesis that the Soviet occupation was illegal, and all actions of the Soviet Union related to the occupation are regarded as contrary to international law in general and to the bilateral treaties between the USSR and the three Baltic countries in particular.

The Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1940 refers to the military occupation of the Republic of Latvia by the Soviet Union under the provisions of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany and its Secret Additional Protocol signed in August 1939.

The German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty was a second supplementary protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939. It was a secret clause as amended on 28 September 1939 by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union after their joint invasion and occupation of sovereign Poland. It was signed by Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov, the foreign ministers of Germany and the Soviet Union respectively, in the presence of Joseph Stalin. Only a small portion of the protocol, which superseded the first treaty, was publicly announced, while the spheres of influence of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union remained secret. The third secret protocol of the Pact was signed on 10 January 1941 by Friedrich Werner von Schulenburg and Molotov, in which Germany renounced its claims on a part of Lithuania, west of the Šešupė river. Only a few months after this, Germany started its invasion of the Soviet Union.

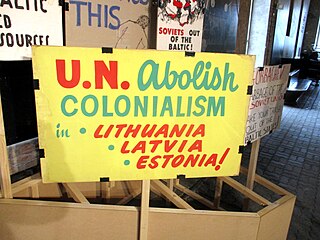

The Select Committee to Investigate Communist Aggression and the Forced Incorporation of the Baltic States into the U.S.S.R., also known as the Kersten Committee after its chairman, U.S. Representative Charles J. Kersten was established in 1953 to investigate the annexation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the Soviet Union. The committee terminated March 4, 1954, when it was replaced by the Select Committee on Communist Aggression.

The Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty was a bilateral treaty signed between the Soviet Union and Lithuania on October 10, 1939. According to provisions outlined in the treaty, Lithuania would acquire about one fifth of the Vilnius Region, including Lithuania's historical capital, Vilnius, and in exchange would allow five Soviet military bases with 20,000 troops to be established across Lithuania. In essence the treaty with Lithuania was very similar to the treaties that the Soviet Union signed with Estonia on September 28, and with Latvia on October 5. According to official Soviet sources, the Soviet military was strengthening the defenses of a weak nation against possible attacks by Nazi Germany. The treaty provided that Lithuania's sovereignty would not be affected. However, in reality the treaty opened the door for the first Soviet occupation of Lithuania and was described by The New York Times as "virtual sacrifice of independence."

The Baltics Are Waking Up! is a trilingual song composed by Boriss Rezņiks for the occasion of the Baltic Way, a large demonstration against the Soviet Union for independence of the Baltic States in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The song is sometimes regarded as the joint anthem of the Baltics. The Lithuanian text was sung by Žilvinas Bubelis, Latvian by Viktors Zemgals, and Estonian by Tarmo Pihlap.

Relevant events began regarding the Baltic states and the Soviet Union when, following Bolshevist Russia's conflict with the Baltic states—Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia—several peace treaties were signed with Russia and its successor, the Soviet Union. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviet Union and all three Baltic States further signed non-aggression treaties. The Soviet Union also confirmed that it would adhere to the Kellogg–Briand Pact with regard to its neighbors, including Estonia and Latvia, and entered into a convention defining "aggression" that included all three Baltic countries.

The Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Lithuania before midnight of June 14, 1940. The Soviets, using a formal pretext, demanded that an unspecified number of Soviet soldiers be allowed to enter the Lithuanian territory and that a new pro-Soviet government be formed. The ultimatum and subsequent incorporation of Lithuania into the Soviet Union stemmed from the division of Eastern Europe into the German and Soviet spheres of influence agreed in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939. Lithuania, along with Latvia and Estonia, fell into the Soviet sphere. According to the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty of October 1939, Lithuania agreed to allow some 20,000 Soviets troops to be stationed at bases within Lithuania in exchange for receiving a portion of the Vilnius Region. Further Soviet actions to establish its dominance in its sphere of influence were delayed by the Winter War with Finland and resumed in spring 1940 when Germany was making rapid advances in western Europe. Despite the threat to the country's independence, Lithuanian authorities did little to plan for contingencies and were unprepared for the ultimatum.

The Baltic Appeal was a public letter to the secretary-general of the United Nations, Soviet Union, East and West Germany, and signatories of the Atlantic Charter by 45 Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian citizens. Sent on 23 August 1979, the 40th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, the appeal demanded public disclosure of the pact and its secret protocols, annulment of the pact ab initio, and restoration of the independence of the Baltic states, then occupied by the Soviet Union.

The People's Government of Lithuania was a puppet cabinet installed by the Soviet Union in Lithuania immediately after Lithuania's acceptance of the Soviet ultimatum of June 14, 1940. The formation of the cabinet was supervised by Vladimir Dekanozov, deputy of Vyacheslav Molotov and a close associate of Lavrentiy Beria, who selected Justas Paleckis as the prime minister and acting president. The government was formed on June 17 and, together with the People's Seimas (parliament), transitioned independent Lithuania to a socialist republic and the 14th republic of the Soviet Union thus legitimizing the Soviet occupation of Lithuania. The People's Government was replaced by the Council of People's Commissars of the Lithuanian SSR on August 25. Similar transitional People's Governments were formed in Latvia and Estonia.

The Lithuanian Liberty League or LLL was a dissident organization in the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic and a political party in independent Republic of Lithuania. Established as an underground resistance group in 1978, LLL was headed by Antanas Terleckas. Pro-independence LLL published anti-Soviet literature and organized protest rallies. While it enjoyed limited popularity in 1987–1989, it grew increasingly irrelevant after the independence declaration in 1990. It registered as a political party in November 1995 and participated in parliamentary elections without gaining any seats in the Seimas.

The Black Ribbon Day, officially known in the European Union as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism and also referred to as the Europe-wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, is an international day of remembrance for victims of totalitarianism regimes, specifically Stalinist, communist, Nazi and fascist regimes. Formally recognised by the European Union, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and some other countries, it is observed on 23 August. It symbolises the rejection of "extremism, intolerance and oppression" according to the European Union. The purpose of the Day of Remembrance is to preserve the memory of the victims of mass deportations and exterminations, while promoting democratic values to reinforce peace and stability in Europe. It is one of the two official remembrance days or observances of the European Union, alongside Europe Day. Under the name Black Ribbon Day it is an official remembrance day of Canada. The European Union has used both names alongside each other.

The background of the occupation of the Baltic states covers the period before the first Soviet occupation on 14 June 1940, stretching from independence in 1918 to the Soviet ultimatums in 1939–1940. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia gained independence in the aftermath of the Russian revolutions of 1917 and the German occupation which in the Baltic countries lasted until the end of World War I in November 1918. All three countries signed non-aggression treaties with the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. Despite the treaties, in the aftermath of the 1939 German–Soviet pact, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were occupied, and thereafter forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union, in 1940.

The three Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – were re-occupied in 1944–1945 by the Soviet Union (USSR) following the German occupation. The Baltic states regained independence in 1990–1991.

The Soviet economic blockade of Lithuania was imposed by the Soviet Union on Lithuania between 18 April and 2 July 1990.