This article needs additional citations for verification .(March 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

A court is an extended royal household in a monarchy, including all those who regularly attend on a monarch, or another central figure. Hence the word court may also be applied to the coterie of a senior member of the nobility.

A monarchy is a form of government in which a group, generally a group of people comprising a dynasty, embodies the country's national identity and its head, the monarch, exercises the role of sovereign. The power of the monarch may vary from purely symbolic, to partial and restricted, to completely autocratic. In most cases the monarch's position is inherited and lasts until death or abdication. In contrast, elective monarchies require the monarch to be elected. Both types have further variations as there are widely divergent structures and traditions defining monarchy. For example, in some elected monarchies family history is the only criterion for eligibility to be monarch, whereas many hereditary monarchies impose requirements regarding the religion, age, gender, or mental capacity. Occasionally this can result in more than one rival claimants, whose legitimacy is subject to election. There have been cases where the term of a monarch's reign either is fixed in years or continues until certain conditions are satisfied: an invasion being repulsed, for instance.

Nobility is a social class in aristocracy, normally ranked immediately under royalty, that possesses more acknowledged privileges and higher social status than most other classes in a society and with membership thereof typically being hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles, or may be largely honorary, and vary by country and era. The Medieval chivalric motto "noblesse oblige", meaning literally "nobility obligates", explains that privileges carry a lifelong obligation of duty to uphold various social responsibilities of, e.g., honorable behavior, customary service, or leadership roles or positions, that lives on by a familial or kinship bond.

Contents

- Patronage

- Court culture

- History

- Early history

- East Asia

- Medieval Europe

- Africa

- Caliphate courts

- Court officials

- Court seats

- Examples of court seats in fiction

- Court Structure and Titles

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- Antiquity

- Middle Ages

- Renaissance and Early Modern

- External links

Royal courts may have their seat in a designated place, several specific places, or be a mobile, itinerant court.

The modern capital city has, historically, not always existed. In medieval Western Europe, a migrating form of government was more common: the itinerant court or travelling kingdom. This was the only existing West European form of kingship in the Early Middle Ages, and remained so until around the middle of the thirteenth century, when permanent (stationary) royal residences began to develop - i.e. embryonic capital cities.

In the largest courts, the royal households, many thousands of individuals comprised the court. These courtiers included the monarch or noble's camarilla and retinue, household, nobility, those with court appointments, bodyguard, and may also include emissaries from other kingdoms or visitors to the court. Foreign princes and foreign nobility in exile may also seek refuge at a court.

A royal household or imperial household is the residence and administrative headquarters in ancient and post-classical monarchies, and papal household for popes, and formed the basis for the general government of the country as well as providing for the needs of the sovereign and their relations.

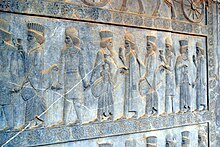

A courtier is a person who is often in attendance at the court of a monarch or other royal personage. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the residence of the monarch, and the social and political life were often completely mixed together.

A camarilla is a group of courtiers or favourites who surround a king or ruler. Usually, they do not hold any office or have any official authority at the royal court but influence their ruler behind the scenes. Consequently, they also escape having to bear responsibility for the effects of their advice. The term derives from the Spanish word camarilla, meaning "little chamber" or private cabinet of the king. It was first used of the circle of cronies around Spanish King Ferdinand VII. The term involves what is known as cronyism. The term also entered other languages like the German and Greek, and is used in the sense given above.

Near Eastern and Eastern courts often included the harem and concubines as well as eunuchs who fulfilled a variety of functions. At times, the harem was walled off and separate from the rest of the residence of the monarch. In Asia, concubines were often a more visible part of the court.

The term Eastern world refers to various cultures or social structures and philosophical systems depending on the context, most often including at least part of Asia or geographically the countries and cultures east of Europe, the Mediterranean Region and Arab world, specifically in historical (pre-modern) contexts, and in modern times in the context of Orientalism.

Harem, also known as zenana in the Indian subcontinent, properly refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family and are inaccessible to adult males except for close relations. This private space has been traditionally understood as serving the purposes of maintaining the modesty, privilege, and protection of women. A harem may house a man's wife — or wives and concubines, as in royal harems of the past — their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic workers, and other unmarried female relatives.In former times some harems were guarded by eunuchs who were allowed inside. The structure of the harem and the extent of monogamy or polygamy has varied depending on the family's personalities, socio-economic status, and local customs. Similar institutions have been common in other Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilizations, especially among royal and upper-class families, and the term is sometimes used in other contexts.

Asia is Earth's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the Eastern and Northern Hemispheres. It shares the continental landmass of Eurasia with the continent of Europe and the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with both Europe and Africa. Asia covers an area of 44,579,000 square kilometres (17,212,000 sq mi), about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area. The continent, which has long been home to the majority of the human population, was the site of many of the first civilizations. Asia is notable for not only its overall large size and population, but also dense and large settlements, as well as vast barely populated regions. Its 4.5 billion people constitute roughly 60% of the world's population.

Lower ranking servants and bodyguards were not properly called courtiers, though they might be included as part of the court or royal household in the broadest definition. Entertainers and others may have been counted as part of the court.

A bodyguard is a type of security guard, or government law enforcement officer, or soldier who protects a person or a group of people—usually high-ranking public officials or officers, wealthy people, and celebrities—from danger: generally theft, assault, kidnapping, assassination, harassment, loss of confidential information, threats, or other criminal offences. The personnel team that protects a VIP is often referred to as the VIP's security detail.