In grammar, tense is a category that expresses time reference. Tenses are usually manifested by the use of specific forms of verbs, particularly in their conjugation patterns.

Dagbani, also known as Dagbanli or Dagbanle, is a Gur language spoken in Ghana and Northern Togo. Its native speakers are estimated around 1,170,000. Dagbani is the most widely spoken language in northern Ghana, specifically among the tribes that fall under the authority of the King of Dagbon, known as the Yaa-Naa. Dagbon is a traditional kingdom situated in northern Ghana, and the Yaa-Naa is the paramount chief or king who governs over the various tribes and communities within the Dagbon kingdom.

Rapa Nui or Rapanui, also known as Pascuan or Pascuense, is an Eastern Polynesian language of the Austronesian language family. It is spoken on Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui.

Vaeakau-Taumako is a Polynesian language spoken in some of the Reef Islands as well as in the Taumako Islands in the Temotu province of Solomon Islands.

Najdi Arabic is the group of Arabic varieties originating from the Najd region of Saudi Arabia. Outside of Saudi Arabia, it is also the main Arabic variety spoken in the Syrian Desert of Iraq, Jordan, and Syria as well as the westernmost part of Kuwait.

Cavineña is an indigenous language spoken on the Amazonian plains of northern Bolivia by over 1,000 Cavineño people. Although Cavineña is still spoken, it is an endangered language. Guillaume (2004) states that about 1200 people speak the language, out of a population of around 1700. Nearly all Cavineña are bilingual in Spanish.

Apma is the language of central Pentecost island in Vanuatu. Apma is an Oceanic language. Within Vanuatu it sits between North Vanuatu and Central Vanuatu languages, and combines features of both groups.

Ughele is an Oceanic language spoken by about 1200 people on Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

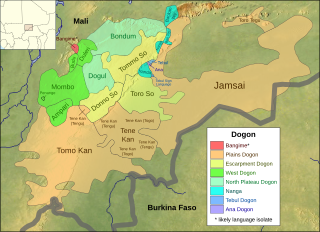

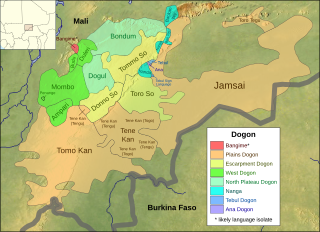

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

Pichinglis, commonly referred to by its speakers as Pichi and formally known as Fernando Po Creole English (Fernandino), is an Atlantic English-lexicon creole language spoken on the island of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea. It is an offshoot of the Krio language of Sierra Leone, and was brought to Bioko by Krios who immigrated to the island during the colonial era in the 19th century.

Baiso or Bayso is a Lowland East Cushitic language belonging to the Omo–Tana subgroup, and is spoken in Ethiopia, in the region around Lake Abaya.

In linguistics, affect is an attitude or emotion that a speaker brings to an utterance. Affects such as sarcasm, contempt, dismissal, distaste, disgust, disbelief, exasperation, boredom, anger, joy, respect or disrespect, sympathy, pity, gratitude, wonder, admiration, humility, and awe are frequently conveyed through paralinguistic mechanisms such as intonation, facial expression, and gesture, and thus require recourse to punctuation or emoticons when reduced to writing, but there are grammatical and lexical expressions of affect as well, such as pejorative and approbative or laudative expressions or inflections, adversative forms, honorific and deferential language, interrogatives and tag questions, and some types of evidentiality.

Yolmo (Hyolmo) or Helambu Sherpa, is a Tibeto-Burman language of the Hyolmo people of Nepal. Yolmo is spoken predominantly in the Helambu and Melamchi valleys in northern Nuwakot District and northwestern Sindhupalchowk District. Dialects are also spoken by smaller populations in Lamjung District and Ilam District and also in Ramecchap District. It is very similar to Kyirong Tibetan and less similar to Standard Tibetan and Sherpa. There are approximately 10,000 Yolmo speakers, although some dialects have larger populations than others.

Farefare or Frafra, also known by the regional name of Gurenne (Gurene), is a Niger–Congo language spoken by the Frafra people of northern Ghana, particularly the Upper East Region, and southern Burkina Faso. It is a national language of Ghana, and is closely related to Dagbani and other languages of Northern Ghana, and also related to Mossi, also known as Mooré, the national language of Burkina Faso.

Iatmul is the language of the Iatmul people, spoken around the Sepik River in the East Sepik Province, northern Papua New Guinea. The Iatmul, however, do not refer to their language by the term Iatmul, but call it gepmakudi.

Konkomba is a Gurma language spoken in Ghana, Togo and Burkina Faso.

Bandial (Banjaal), or Eegima (Eegimaa), is a Jola language of the Casamance region of Senegal. The three dialects, Affiniam, Bandial proper, and Elun are divergent, on the border between dialects and distinct languages.

Buli, or Kanjaga, is a Gur language of Ghana primarily spoken in the Builsa District, located in the Upper East Region of the country. It is an SVO language and has 200 000 speakers.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Neverver (Nevwervwer), also known as Lingarak, is an Oceanic language. Neverver is spoken in Malampa Province, in central Malekula, Vanuatu. The names of the villages on Malekula Island where Neverver is spoken are Lingarakh and Limap.