Vaeakau-Taumako is a Polynesian language spoken in some of the Reef Islands as well as in the Taumako Islands in the Temotu province of Solomon Islands.

The Nafsan language, also known as South Efate or Erakor, is a Southern Oceanic language spoken on the island of Efate in central Vanuatu. As of 2005, there are approximately 6,000 speakers who live in coastal villages from Pango to Eton. The language's grammar has been studied by Nick Thieberger, who has produced a book of stories and a dictionary of the language.

Sulka is a language isolate of New Britain, Papua New Guinea. In 1991, there were 2,500 speakers in eastern Pomio District, East New Britain Province. Villages include Guma in East Pomio Rural LLG. With such a low population of speakers, this language is considered to be endangered. Sulka speakers had originally migrated to East New Britain from New Ireland.

Tamambo, or Malo, is an Oceanic language spoken by 4,000 people on Malo and nearby islands in Vanuatu. It is one of the most conservative Southern Oceanic languages.

Apma is the language of central Pentecost island in Vanuatu. Apma is an Oceanic language. Within Vanuatu it sits between North Vanuatu and Central Vanuatu languages, and combines features of both groups.

Roviana is a member of the North West Solomonic branch of Oceanic languages. It is spoken around Roviana and Vonavona lagoons at the north central New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. It has 10,000 first-language speakers and an additional 16,000 people mostly over 30 years old speak it as a second language. In the past, Roviana was widely used as a trade language and further used as a lingua franca, especially for church purposes in the Western Province, but now it is being replaced by the Solomon Islands Pijin. Published studies on Roviana include: Ray (1926), Waterhouse (1949) and Todd (1978) contain the syntax of Roviana. Corston-Oliver discuss ergativity in Roviana. Todd (2000) and Ross (1988) discuss the clause structure in Roviana. Schuelke (2020) discusses grammatical relations and syntactic ergativity in Roviana.

Ughele is an Oceanic language spoken by about 1200 people on Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

Dagaare is the language of the Dagaaba people of Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast. It has been described as a dialect continuum that also includes Waale and Birifor. Dagaare language varies in dialect stemming from other family languages including: Dagbane, Waale, Mabia, Gurene, Mampruli, Kusaal, Buli, Niger-Congo, and many other sub languages resulting in around 1.3 million Dagaare speakers. Throughout the regions of native Dagaare speakers the dialect comes from Northern, Central, Western, and Southern areas referring to the language differently. Burkina Faso refers to Dagaare as Dagara and Birifor to natives in the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire. The native tongue is still universally known as Dagaare. Amongst the different dialects, the standard for Dagaare is derived from the Central region's dialect. Southern Dagaare also stems from the Dagaare language and is known to be commonly spoken in Wa and Kaleo.

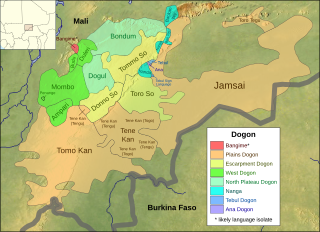

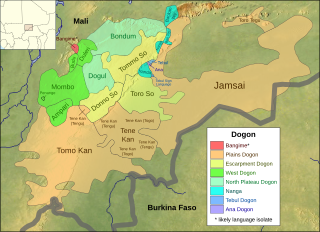

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

The Karbi language is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken by the Karbi people of Northeastern India.

Kasena or Kassena is the language of the Kassena ethnic group and is a Gur language spoken in the Upper East Region of northern Ghana and in Burkina Faso.

Farefare or Frafra, also known by the regional name of Gurenne (Gurene), is a Niger–Congo language spoken by the Frafra people of northern Ghana, particularly the Upper East Region, and southern Burkina Faso. It is a national language of Ghana, and is closely related to Dagbani and other languages of Northern Ghana, and also related to Mossi, also known as Mooré, the national language of Burkina Faso.

Konkomba is a Gurma language spoken in Ghana, Togo and Burkina Faso.

Bandial (Banjaal), or Eegima (Eegimaa), is a Jola language of the Casamance region of Senegal. The three dialects, Affiniam, Bandial proper, and Elun are divergent, on the border between dialects and distinct languages.

Buli, or Kanjaga, is a Gur language of Ghana primarily spoken in the Builsa District, located in the Upper East Region of the country. It is an SVO language and has 200 000 speakers.

Mavea is an Oceanic language spoken on Mavea Island in Vanuatu, off the eastern coast of Espiritu Santo. It belongs to the North–Central Vanuatu linkage of Southern Oceanic. The total population of the island is approximately 172, with only 34 fluent speakers of the Mavea language reported in 2008.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Toʼabaita, also known as Toqabaqita, Toʼambaita, Malu and Maluʼu, is a language spoken by the people living at the north-western tip of Malaita Island, of South Eastern Solomon Islands. Toʼabaita is an Austronesian language.

Baluan-Pam is an Oceanic language of Manus Province, Papua New Guinea. It is spoken on Baluan Island and on nearby Pam Island. The number of speakers, according to the latest estimate based on the 2000 Census, is 2,000. Speakers on Baluan Island prefer to refer to their language with its native name Paluai.

Lengo or informally known as "Doku" is an Oceanic language spoken on the island of Guadalcanal. It belongs to the Southeast Solomonic language family.