Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniotic, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all tetrapods, excluding the amniotes. All extant (living) amphibians belong to the monophyletic subclass Lissamphibia, with three living orders: Anura (frogs), Urodela (salamanders), and Gymnophiona (caecilians). Evolved to be mostly semiaquatic, amphibians have adapted to inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living in freshwater, wetland or terrestrial ecosystems. Their life cycle typically starts out as aquatic larvae with gills known as tadpoles, but some species have developed behavioural adaptations to bypass this.

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All ten extant salamander families are grouped together under the order Urodela from the group Caudata. Salamander diversity is highest in eastern North America, especially in the Appalachian Mountains; most species are found in the Holarctic realm, with some species present in the Neotropical realm.

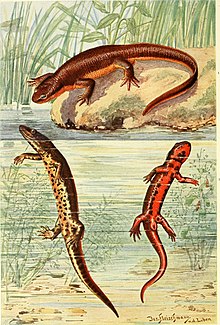

The smooth newt, European newt, northern smooth newt or common newt is a species of newt. It is widespread in Europe and parts of Asia, and has been introduced into Australia. Individuals are brown with a spotted underside that ranges in colour from orange to white. They reach an average length of 8–11 cm (3.1–4.3 in); males are larger than females. The newts' skins are dry and velvety when they are living on land, but become smooth when they migrate into the water to breed. Males develop a more vivid colour pattern and a conspicuous skin seam (crest) on their back when breeding.

Salamandridae is a family of salamanders consisting of true salamanders and newts. Salamandrids are distinguished from other salamanders by the lack of rib or costal grooves along the sides of their bodies and by their rough skin. Their skin is very granular because of the number of poison glands. They also lack nasolabial grooves. Most species of Salamandridae have moveable eyelids but lack lacrimal glands.

The northern crested newt, great crested newt or warty newt is a newt species native to Great Britain, northern and central continental Europe and parts of Western Siberia. It is a large newt, with females growing up to 16 cm (6.3 in) long. Its back and sides are dark brown, while the belly is yellow to orange with dark blotches. Males develop a conspicuous jagged crest on their back and tail during the breeding season.

The sword-tail newt, sword-tailed newt, yellow-bellied newt, or Okinawa newt is a species of true salamander from the Ryukyu Archipelago in Japan.

The Chinese fire belly newt is a small black newt, with bright-orange aposematic coloration on their ventral sides. C. orientalis is commonly seen in pet stores, where it is frequently confused with the Japanese fire belly newt due to similarities in size and coloration. C. orientalis typically exhibits smoother skin and a rounder tail than C. pyrrhogaster, and has less obvious parotoid glands.

The eastern newt is a common newt of eastern North America. It frequents small lakes, ponds, and streams or nearby wet forests. The eastern newt produces tetrodotoxin, which makes the species unpalatable to predatory fish and crayfish. It has a lifespan of 12 to 15 years in the wild, and it may grow to 5 in (13 cm) in length. These animals are common aquarium pets, being either collected from the wild or sold commercially. The striking bright orange juvenile stage, which is land-dwelling, is known as a red eft. Some sources blend the general name of the species and that of the red-spotted newt subspecies into the eastern red-spotted newt.

The alpine newt is a species of newt native to continental Europe and introduced to Great Britain and New Zealand. Adults measure 7–12 cm (2.8–4.7 in) and are usually dark grey to blue on the back and sides, with an orange belly and throat. Males are more conspicuously coloured than the drab females, especially during breeding season.

The fire belly newt or fire newt is a genus (Cynops) of newts native to Japan and China. All of the species show bright yellow or red bellies, but this feature is not unique to this genus. Their skin contains a toxin that can be harmful if ingested.

Triturus is a genus of newts comprising the crested and the marbled newts, which are found from Great Britain through most of continental Europe to westernmost Siberia, Anatolia, and the Caspian Sea region. Their English names refer to their appearance: marbled newts have a green–black colour pattern, while the males of crested newts, which are dark brown with a yellow or orange underside, develop a conspicuous jagged seam on their back and tail during their breeding phase.

The rough-skinned newt or roughskin newt is a North American newt known for the strong toxin exuded from its skin.

The red-bellied newt is a newt that is native to coastal woodlands in northern California and is terrestrial for most of its life.

The marbled newt is a mainly terrestrial newt native to western Europe. They are found in the Iberian Peninsula and France, where they typically inhabit mountainous areas.

The Oita salamander is a species of salamander in the family Hynobiidae endemic to Japan. Named after Ōita Prefecture, its natural habitats are temperate forests, rivers, intermittent rivers, freshwater marshes, intermittent freshwater marshes, and irrigated land in western Japan. It is threatened by habitat loss, due to the increasing construction of homes within its habitat. The Oita salamander is considered to be vulnerable by the (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species with a declining population.

The Japanese pond turtle, also called commonly the Japanese pond terrapin and the Japanese pond tortoise, is a species of turtle in the family Geoemydidae endemic to Japan. Its Japanese name is nihon ishigame, Japanese stone turtle. Its population has decreased somewhat due to habitat loss, but it is not yet considered a threatened species.

A newt is a salamander in the subfamily Pleurodelinae. The terrestrial juvenile phase is called an eft. Unlike other members of the family Salamandridae, newts are semiaquatic, alternating between aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Not all aquatic salamanders are considered newts, however. More than 100 known species of newts are found in North America, Europe, North Africa and Asia. Newts metamorphose through three distinct developmental life stages: aquatic larva, terrestrial juvenile (eft), and adult. Adult newts have lizard-like bodies and return to the water every year to breed, otherwise living in humid, cover-rich land habitats.

The Fuding fire belly newt is a rare species of newt in the family Salamandridae, endemic to China. It is only known from Fuding in northeastern Fujian, from the locality where it was described as a new species in 2010. Although it is genetically similar to the Chinese fire belly newt, it is morphologically more similar to the Dayang fire belly newt. The range of C. fudingensis is separate from both other species.

Tylototriton ziegleri, also known as Ziegler's crocodile newt or Ziegler's knobby newt, is a species of newt in the family Salamandridae. It is currently known from Hà Giang and Cao Bằng provinces in northern Vietnam, although its actual range probably wider; there is a photograph to suggest it also occurs in Lào Cai Province in Vietnam, and its range likely extends to Yunnan in southern China. Based on molecular genetic data, Tylototriton ziegleri belongs to the "Tylototriton asperrimus group" of newts. The specific name ziegleri honours Thomas Ziegler, a German herpetologist.

Sexual selection in amphibians involves sexual selection processes in amphibians, including frogs, salamanders and newts. Prolonged breeders, the majority of frog species, have breeding seasons at regular intervals where male-male competition occurs with males arriving at the waters edge first in large number and producing a wide range of vocalizations, with variations in depth of calls the speed of calls and other complex behaviours to attract mates. The fittest males will have the deepest croaks and the best territories, with females making their mate choices at least partly based on the males depth of croaking. This has led to sexual dimorphism, with females being larger than males in 90% of species, males in 10% and males fighting for groups of females.