Arkose or arkosic sandstone is a detrital sedimentary rock, specifically a type of sandstone containing at least 25% feldspar. Arkosic sand is sand that is similarly rich in feldspar, and thus the potential precursor of arkose.

Rapakivi granite is an igneous intrusive rock and variant of alkali feldspar granite. It is characterized by large, rounded crystals of orthoclase each with a rim of oligoclase. Common mineral components include hornblende and biotite. The name has come to be used most frequently as a textural term where it implies plagioclase rims around orthoclase in plutonic (intrusive) rocks. Rapakivi is a Finnish compound of "rapa" and "kivi", because the different heat expansion coefficients of the component minerals make exposed rapakivi crumble easily into sand.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic to refer to sedimentary rocks and particles in sediment transport, whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

The Newark Supergroup, also known as the Newark Group, is an assemblage of Upper Triassic and Lower Jurassic sedimentary and volcanic rocks which outcrop intermittently along the east coast of North America. They were deposited in a series of Triassic basins, the Eastern North American rift basins, approximately 220–190 million years ago. The basins are characterized as aborted rifts, with half-graben geometry, developing parallel to the main rift of the Atlantic Ocean which formed as North America began to separate from Africa. Exposures of the Newark Supergroup extend from South Carolina north to Nova Scotia. Related basins are also found underwater in the Bay of Fundy. The group is named for the city of Newark, New Jersey.

The geology of Tasmania is complex, with the world's biggest exposure of diabase, or dolerite. The rock record contains representatives of each period of the Neoproterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras. It is one of the few southern hemisphere areas that were glaciated during the Pleistocene with glacial landforms in the higher parts. The west coast region hosts significant mineralisation and numerous active and historic mines.

The Hogland Series are a series of Subjotnian sedimentary rocks exposed on the island of Gogland, the Sommer Islands and the nearby sea floor in the Gulf of Finland. The series encompass quartz-rich conglomerates and breccias, as well as some volcanic rocks of mafic composition in the form of lava flows and some more silica-rich igneous rocks including quartz-porphyry. The porphyries, which lie at the top the pile, share their origin with the rapakivi granites located nearby. An exhumed Subjotnian erosion surface is exposed on the island.

The Hallandian-Danopolonian event was an orogeny and thermal event that affected Baltica in the Mesoproterozoic. The event metamorphosed pre-existing rocks and generated magmas that crystallized into granite. The Hallandian-Danopolonian event has been suggested to be responsible for forming an east-west alignment of sedimentary basins hosting Jotnian sediments spanning from eastern Norway, to Lake Ladoga in Russia. The alignment of subsidence is thought to correspond to an ancient back-arc basin parallel to a subduction zone further south.

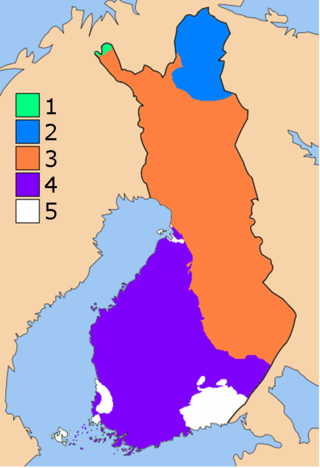

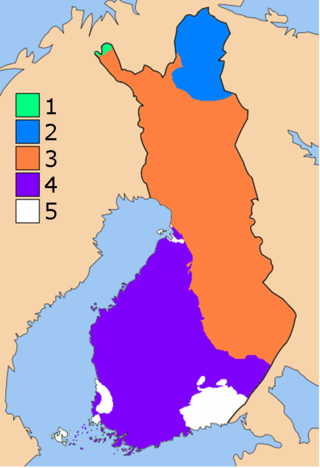

The geology of Finland is made up of a mix of geologically very young and very old materials. Common rock types are orthogneiss, granite, metavolcanics and metasedimentary rocks. On top of these lies a widespread thin layer of unconsolidated deposits formed in connection to the Quaternary ice ages, for example eskers, till and marine clay. The topographic relief is rather subdued because mountain massifs were worn down to a peneplain long ago.

The Satakunta dyke swarms are a series of dyke swarms, a group of magmatic intrusions, of Mesoproterozoic age in the Bothnian Sea and western and central Finland. They are made up of Subjotnian diabase dikes, associated with rapakivi magmatism. They were most likely formed on the Columbia supercontinent.

Harry von Eckermann (1886–1969) was a Swedish industrialist, mineralogist and geologist. His studies were centered around anorogenic alkaline igneous rocks occurring in the Baltic Shield. Following this line he studied the Alnö Complex, Norra Kärr Alkaline Complex and various Rapakivi granites.

The geology of Liberia is largely extremely ancient rock formed between 3.5 billion and 539 million years ago in the Archean and the Neoproterozoic, with some rocks from the past 145 million years near the coast. The country has rich iron resources as well as some diamonds, gold and other minerals in ancient sediment formations weathered to higher concentrations by tropical rainfall.

The geology of Ghana is primarily very ancient crystalline basement rock, volcanic belts and sedimentary basins, affected by periods of igneous activity and two major orogeny mountain building events. Aside from modern sediments and some rocks formed within the past 541 million years of the Phanerozoic Eon, along the coast, many of the rocks in Ghana formed close to one billion years ago or older leading to five different types of gold deposit formation, which gave the region its former name Gold Coast.

The geology of Niger comprises very ancient igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rocks in the west, more than 2.2 billion years old formed in the late Archean and Proterozoic eons of the Precambrian. The Volta Basin, Air Massif and the Iullemeden Basin began to form in the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic, along with numerous ring complexes, as the region experienced events such as glaciation and the Pan-African orogeny. Today, Niger has extensive mineral resources due to complex mineralization and laterite weathering including uranium, molybdenum, iron, coal, silver, nickel, cobalt and other resources.

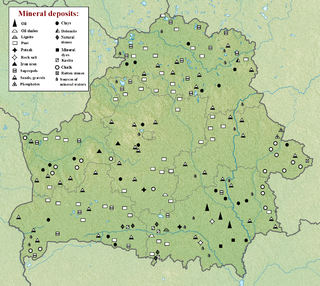

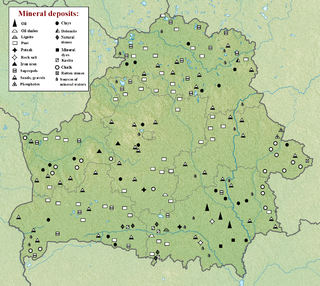

The geology of Belarus began to form more than 2.5 billion years ago in the Precambrian, although many overlying sedimentary units deposited during the Paleozoic and the current Quaternary. Belarus is located in the eastern European plain. From east to west it covers about 650 kilometers while from north to south it covers about 560 kilometers, and the total area is about 207,600 square kilometers. It borders Poland in the north, Lithuania in the northwest, Latvia and Russia in the north, and Ukraine in the south. Belarus has a planar topography with a height of about 160 m above sea level. The highest elevation at 346 meters above sea level is Mt. Dzerzhinskaya, and the lowest point at the height of 80 m is in the Neman River valley.

The geology of Sweden is the regional study of rocks, minerals, tectonics, natural resources and groundwater in the country. The oldest rocks in Sweden date to more than 2.5 billion years ago in the Precambrian. Complex orogeny mountain building events and other tectonic occurrences built up extensive metamorphic crystalline basement rock that often contains valuable metal deposits throughout much of the country. Metamorphism continued into the Paleozoic after the Snowball Earth glaciation as the continent Baltica collided with an island arc and then the continent Laurentia. Sedimentary rocks are most common in southern Sweden with thick sequences from the last 250 million years underlying Malmö and older marine sedimentary rocks forming the surface of Gotland.

The geology of Bhutan is less well studied than many countries in Asia, together with the broader Eastern Himalayas region. Older Paleozoic and Precambrian rocks often appear mixed together with younger sediments due to the Himalayan orogeny.

The geology of Montana includes thick sequences of Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks overlying ancient Archean and Proterozoic crystalline basement rock. Eastern Montana has considerable oil and gas resources, while the uplifted Rocky Mountains in the west, which resulted from the Laramide orogeny and other tectonic events have locations with metal ore.

Geology of Latvia includes an ancient Archean and Proterozoic crystalline basement overlain with Neoproterozoic volcanic rocks and numerous sedimentary rock sequences from the Paleozoic, some from the Mesozoic and many from the recent Quaternary past. Latvia is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe.

The geology of Åland includes Jotnian age sediments from the Proterozoic, such as sandstone, siltstone, arkose, conglomerate and shale. The islands are underlain by plutonic rocks common of the Svecofennian Domain.