Theory of mind

Mind-blindness is defined as a state where the ToM has not been developed in an individual. [1] According to the theory, non-autistic people can make automatic interpretations of events taking into consideration the mental states of people, their desires, and beliefs. Individuals lacking ToM would therefore perceive the world in a confusing and frightening manner, leading to a social withdrawal. [1] The theory was based on the assumption that biology is linked to autistic behavior, so it was expected that a delayed development or lack of ToM would lead to additional psychiatric complications. Research into a model with more than two categories was also considered. [1]

Mind-blindness, a lack of ToM, was later theorised to be equivalent to a lack of empathy, [4] although research published a year later suggests there is considerable overlap but not complete equivalence. [19] It was empirically demonstrated that processing of complex cognitive emotions is more difficult than processing simpler emotions. In addition, evidence existed at the time that autism was not correlated with the failure of social bonding and attachment in childhood. This was interpreted to suggest that emotion is a component of social cognition that is separable from mentalizing. [3]

Biological basis

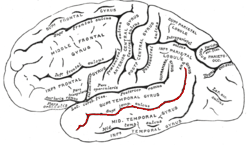

Since the frontal lobe is associated with executive function, it was predicted that the frontal lobe plays an important role in ToM; that executive function and ToM share the same functional regions in the brain. [20] Damage to the frontal lobe is known to affect ToM, [21] [22] partially confirming this hypothesis. From a 2000 study, it was found that a neural network that comprised the medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, the circumscribed region of the anterior paracingulate cortex and the superior temporal sulcus, is crucial for the normal functioning of ToM and self monitoring. [5] [23] Although there is a possibility that ToM and mind-blindness could explain executive function deficits, it was argued that autism is not identified with the failure of executive function alone. [24] It has also been shown that the right temporo-parietal junction behaves differently in those with autism, [25] and the middle cingulate cortex is less active in autistic people during mentalization. [26]