Cardiomyopathy is a group of primary diseases of the heart muscle. Early on there may be few or no symptoms. As the disease worsens, shortness of breath, feeling tired, and swelling of the legs may occur, due to the onset of heart failure. An irregular heart beat and fainting may occur. Those affected are at an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

A premature ventricular contraction (PVC) is a common event where the heartbeat is initiated by Purkinje fibers in the ventricles rather than by the sinoatrial node. PVCs may cause no symptoms or may be perceived as a "skipped beat" or felt as palpitations in the chest. PVCs do not usually pose any danger.

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is an inherited heart disease.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a condition in which muscle tissues of the heart become thickened without an obvious cause. The parts of the heart most commonly affected are the interventricular septum and the ventricles. This results in the heart being less able to pump blood effectively and also may cause electrical conduction problems. Specifically, within the bundle branches that conduct impulses through the interventricular septum and into the Purkinje fibers, as these are responsible for the depolarization of contractile cells of both ventricles.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a condition in which the heart becomes enlarged and cannot pump blood effectively. Symptoms vary from none to feeling tired, leg swelling, and shortness of breath. It may also result in chest pain or fainting. Complications can include heart failure, heart valve disease, or an irregular heartbeat.

Constrictive pericarditis is a condition characterized by a thickened, fibrotic pericardium, limiting the heart's ability to function normally. In many cases, the condition continues to be difficult to diagnose and therefore benefits from a good understanding of the underlying cause.

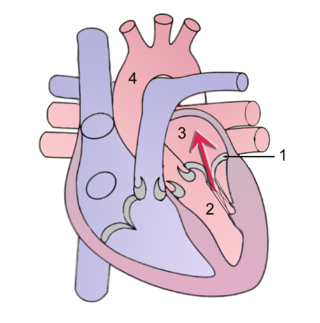

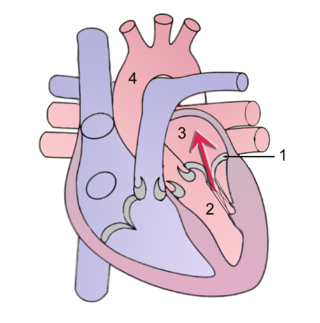

Mitral regurgitation (MR), also known as mitral insufficiency or mitral incompetence, is a form of valvular heart disease in which the mitral valve is insufficient and does not close properly when the heart pumps out blood. It is the abnormal leaking of blood backwards – regurgitation from the left ventricle, through the mitral valve, into the left atrium, when the left ventricle contracts. Mitral regurgitation is the most common form of valvular heart disease.

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is thickening of the heart muscle of the left ventricle of the heart, that is, left-sided ventricular hypertrophy and resulting increased left ventricular mass.

In cardiology, ventricular remodeling refers to changes in the size, shape, structure, and function of the heart. This can happen as a result of exercise or after injury to the heart muscle. The injury is typically due to acute myocardial infarction, but may be from a number of causes that result in increased pressure or volume, causing pressure overload or volume overload on the heart. Chronic hypertension, congenital heart disease with intracardiac shunting, and valvular heart disease may also lead to remodeling. After the insult occurs, a series of histopathological and structural changes occur in the left ventricular myocardium that lead to progressive decline in left ventricular performance. Ultimately, ventricular remodeling may result in diminished contractile (systolic) function and reduced stroke volume.

Ventricular hypertrophy (VH) is thickening of the walls of a ventricle of the heart. Although left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is more common, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), as well as concurrent hypertrophy of both ventricles can also occur.

Uhl anomaly is a rare cardiac malformation that was first identified by Dr. Henry Uhl in 1952. It is characterized by the absence of the right ventricle (RV) myocardium, either entirely or partially, and the replacement of the RV myocardium by nonfunctional fibroelastic tissue that resembles parchment. As of 2010 less than 100 cases have been reported in literature.

Amrinone, also known as inamrinone, and sold as Inocor, is a pyridine phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor. It is a drug that may improve the prognosis in patients with congestive heart failure. Amrinone has been shown to increase the contractions initiated in the heart by high-gain calcium induced calcium release (CICR). The positive inotropic effect of amrinone is mediated by the selective enhancement of high-gain CICR, which contributes to the contraction of myocytes by phosphorylation through cAMP dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and Ca2+ calmodulin kinase pathways.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or takotsubo syndrome (TTS), also known as stress cardiomyopathy, is a type of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in which there is a sudden temporary weakening of the muscular portion of the heart. It usually appears after a significant stressor, either physical or emotional; when caused by the latter, the condition is sometimes called broken heart syndrome.

Tricuspid regurgitation (TR), also called tricuspid insufficiency, is a type of valvular heart disease in which the tricuspid valve of the heart, located between the right atrium and right ventricle, does not close completely when the right ventricle contracts (systole). TR allows the blood to flow backwards from the right ventricle to the right atrium, which increases the volume and pressure of the blood both in the right atrium and the right ventricle, which may increase central venous volume and pressure if the backward flow is sufficiently severe.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to cardiology, the branch of medicine dealing with disorders of the human heart. The field includes medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart disease and electrophysiology. Physicians who specialize in cardiology are called cardiologists.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a form of heart failure in which the ejection fraction – the percentage of the volume of blood ejected from the left ventricle with each heartbeat divided by the volume of blood when the left ventricle is maximally filled – is normal, defined as greater than 50%; this may be measured by echocardiography or cardiac catheterization. Approximately half of people with heart failure have preserved ejection fraction, while the other half have a reduction in ejection fraction, called heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

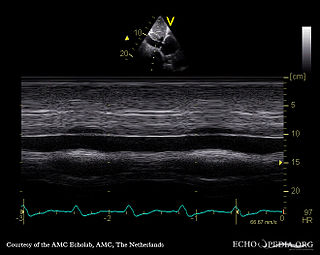

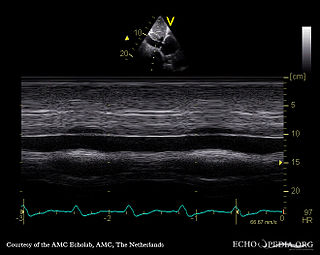

Tissue Doppler echocardiography (TDE) is a medical ultrasound technology, specifically a form of echocardiography that measures the velocity of the heart muscle (myocardium) through the phases of one or more heartbeats by the Doppler effect of the reflected ultrasound. The technique is the same as for flow Doppler echocardiography measuring flow velocities. Tissue signals, however, have higher amplitude and lower velocities, and the signals are extracted by using different filter and gain settings. The terms tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) and tissue velocity imaging (TVI) are usually synonymous with TDE because echocardiography is the main use of tissue Doppler.

Heart problems are more common in people with HIV/AIDS. Those with left ventricular dysfunction have a median survival of 101 days as compared to 472 days in people with AIDS with healthy hearts. HIV is a major cause of cardiomyopathy. The most common type of HIV induced cardiomyopathy is dilated cardiomyopathy also known as eccentric ventricular hypertrophy which leads to impaired contraction of the ventricles due to volume overload. The annual incidence of HIV associated dilated cardiomyopathy was 15.9/1000 before the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). However, in 2014, a study found that 17.6% of HIV patients have dilated cardiomyopathy (176/1000) meaning the incidence has greatly increased.

Ischemic cardiomyopathy is a type of cardiomyopathy caused by a narrowing of the coronary arteries which supply blood to the heart. Typically, patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy have a history of acute myocardial infarction, however, it may occur in patients with coronary artery disease, but without a past history of acute myocardial infarction. This cardiomyopathy is one of the leading causes of sudden cardiac death. The adjective ischemic means characteristic of, or accompanied by, ischemia — local anemia due to mechanical obstruction of the blood supply.

Bernheim syndrome is a presumed disorder wherein the right ventricle is severely compressed due to a shift in the ventricular septal wall of the heart, leading to heart failure. It was first described by Hippolyte Bernheim in 1910. Today, it is argued whether or not Bernheim syndrome is indeed a syndrome or a side effect of other cardiac conditions, such as left ventrical heart failure where the left ventricle is substantially enlarged, encroaching on the space of the right ventricle.