History of endgame literature

The study of a few practical endgames are found in Arabic manuscripts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. However, these are from before the rule of pawn promotion, so most are of little value today. [1] A thirteenth-century Latin book by an unknown author examined the endgame of a knight versus a pawn, and formed the basis of later work by Alexey Troitsky in the twentieth century. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries a few types of endgames were studied, and opposition was known. [2]

Ruy López de Segura's 1561 book contained eight paragraphs on endgames. It used the Spanish rules in effect at the time, so a stalemate and baring the opponent's king were half-wins. [3] In 1617 Pietro Carrera published knowledge of several types of endgames, including queen versus two bishops, two rooks versus a rook and a knight, and two rooks versus a rook and a bishop. Several writers published books developing endgame theory: Gioachino Greco in 1624, Philipp Stamma in 1737, and François-André Philidor in 1749. [4] In 1634 Alessandro Salvio analyzed endgames, including a key position in rook endgames. [5] Philidor's book contained much more endgame analysis than earlier books. The first edition analyzed the rook and bishop versus rook endgame. Later editions covered the bishop and knight checkmate, rook and pawn versus bishop, queen versus rook and pawn, queen versus rook, rook and pawn versus rook (including the Philidor position), queen and pawn versus queen, queen versus pawn on the seventh rank, knight versus pawn, two pawns versus one pawn, and two isolated pawns versus two connected pawns. [6]

In the eighteenth century important books were written by Italians (the "Modenese Masters") Domenico Lorenzo Ponziani, Ercole del Rio (1750), and Giambattista Lolli (1763). [7] Lolli's book was based on del Rio's work and was one of the most important for the next 90 years. He studied the endgame of a queen versus two bishops and agreed with the earlier opinion of Salvio that it was generally a draw. Later this was overturned by computer endgame tablebases, when Ken Thompson found a 71-move solution. However, Lolli did find the unique position of mutual zugzwang in this endgame (see diagram). [8] [9] Lolli's 315-page book was the first giving practical research. His material came from several sources, including analysis by Philidor. [10]

In 1766 Carlo Cozio published analysis of 127 endgame positions, but it was not a practical handbook. [11] In 1851 Bernhard Horwitz and Josef Kling published Chess Studies, or endings of games, which contained 427 positions. In 1884 Horwitz added more than fifty positions to the book, retitled it Chess Studies and End-Games, and completely omitted Kling's name. [12] Other important books were Fins de parties d'echecs by Phillipe Ambroise Durand and Jean-Louis Preti in 1871, and Teoria e pratica del giuoco degli scacchi by Signor Salvioli in 1877. [13] Horowitz and Kling's analysis of the endgame of two bishops versus a knight had been questioned, and was eventually overturned by computer databases (see pawnless chess endgame). [14] In 1864 Alfred Crosskill published analysis of the endgame of rook and bishop versus rook, an endgame that has been studied at least as far back as Philidor in 1749. [15]

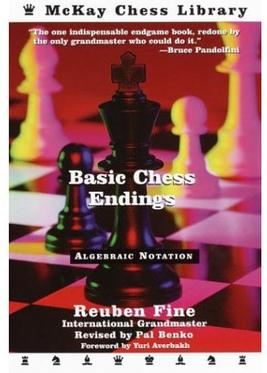

Howard Staunton in The Chess-Player's Handbook, originally published in 1847, included almost 100 pages of analysis of endgames. [16] His analysis of the very rare rook versus three minor pieces endgame is surprisingly sophisticated. Staunton wrote, "Three minor Pieces are much stronger than a Rook, and in cases where two of them are Bishops will usually win without much difficulty, because the player of the Rook is certain to be compelled to lose him for one of his adversary's Pieces. If, however, there are two Knights and one Bishop opposed to a Rook, the latter may generally be exchanged for the Bishop, and as two Knights are insufficient of themselves to force checkmate, the game will be drawn." [17] Writing shortly before Staunton, George Walker reached the same conclusions. [18] Modern-day endgame tablebases confirm Walker and Staunton's assessments of both endings. [19] Yet Reuben Fine, 94 years after Staunton, erroneously wrote in Basic Chess Endings that both types of rook versus three minor piece endings "are theoretically drawn". [20] Grandmaster Pal Benko, an endgame authority and like Fine a world-class player at his peak, perpetuated Fine's error in his 2003 revision of Basic Chess Endings. [21] Grandmaster Andrew Soltis in a 2004 book expressly disagreed with Staunton, claiming that rook versus two bishops and knight is drawn with correct play. [22] Endgame tablebases had already proven that Staunton was correct, and Soltis wrong, although it can take up to 68 moves to win. [23]

The modern period of chess endgame books begins with Theorie und Praxis der Endspiele (Theory and practice of the Endgame) by Johann Berger. This was published in 1891, revised in 1922, and supplemented in 1933. This was the standard work on practical endgames for decades. [24] Many later books were based on Berger's book. [25] Edward Freeborough wrote a 130-page book of analysis of the queen versus rook endgame, The Chess Ending, King & Queen against King & Rook, which was published in 1895. Henri Rinck (1870-1952) was a specialist in pawnless endgames and A. A. Troitsky (1866-1942) is famous for his analysis of two knights versus a pawn. [26] In 1927 Ilya Rabinovich published a comprehensive book in Russian titled The Endgame, which was designed for teaching. An updated version appeared in 1938. [27] (An English version of the second edition was published in 2012 as The Russian Endgame Handbook.) Eugene Znosko-Borovsky published How to Play Chess Endings in 1940.

In 1941, Reuben Fine published Basic Chess Endings , an attempt to collect all practical endgame knowledge into one volume. It is still useful today and has been revised by Pal Benko. [28] Half of André Chéron's (1895–1980) book Traite Complet d'Echecs was about the endgame, and later he wrote Nouveau Traite Complet d'Echecs, which was a large book about the endgame. He later expanded that into the four-volume Lehr- und Handbuch der Endspiele in German, which was translated from the 1952 version in French. [29] This was a major work for endgame studies but was not designed for the practical player.

Yuri Averbakh published a monumental set of books in Russian in 1956. The works were first published in English as several individual books (Pawn Endings, Bishop Endings, Knight Endings, Bishop v. Knight Endings, Rook Endings, Queen and Pawn Endings, Queen v. Rook/Minor Piece Endings, Rook v. Minor Piece Endings) and later collected into the five-volume Comprehensive Chess Endings. It was also published in other languages. [30] Bobby Fischer had these books sent to him during his World Championship match. [31] World Champion Max Euwe published the comprehensive eight-volume Das Endspiel in 1957. [32]

Some other major endgame books are Rook Endings by Grigory Levenfish and Vasily Smyslov (1971), Practical Chess Endings by Paul Keres (1973), Fundamental Chess Endings by Karsten Müller and Frank Lamprecht (2001), Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual by Mark Dvoretsky (2003), and Silman's Complete Endgame Course by Jeremy Silman (2007).