Prince George's County is located in the U.S. state of Maryland bordering the eastern portion of Washington, D.C. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 967,201, making it the second-most populous county in Maryland, behind neighboring Montgomery County. The 2020 census counted an increase of nearly 104,000 in the previous ten years. Its county seat is Upper Marlboro. It is the largest and the second most affluent African American-majority county in the United States, with five of its communities identified in a 2015 top ten list.

Beltsville is a census-designated place (CDP) in northern Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. The community was named for Truman Belt, a local landowner. The 2020 census counted 20,133 residents. Beltsville includes the unincorporated community of Vansville.

Laurel is a city in Maryland, United States, located midway between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore on the banks of the Patuxent River. While the city limits are entirely in northern Prince George's County, outlying developments extend into Anne Arundel, Montgomery and Howard counties. Founded as a mill town in the early 19th century, Laurel expanded local industry and was later able to become an early commuter town for Washington and Baltimore workers following the arrival of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1835. Largely residential today, the city maintains a historic district centered on its Main Street, highlighting its industrial past.

Calvert Cliffs State Park is a public recreation area in Lusby, Calvert County, Maryland, that protects a portion of the cliffs that extend for 24 miles along the eastern flank of the Calvert Peninsula on the west side of Chesapeake Bay from Chesapeake Beach southward to Drum Point. The state park is known for the abundance of mainly Middle Miocene sub-epoch fossils that can be found on the shoreline.

Charles Hazelius Sternberg was an American fossil collector and paleontologist. He was active in both fields from 1876 to 1928, and collected fossils for Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel C. Marsh, and for the British Museum, the San Diego Natural History Museum and other museums.

Muirkirk is an unincorporated community in northern Prince George's County, Maryland, United States, located between Baltimore and Washington in the central part of the state.

Hill-Annex Mine State Park is a state park of Minnesota, United States, interpreting the open-pit mining heritage of the Mesabi Range. The park is located north of the city of Calumet, in Itasca County, Minnesota. The park provides access to fossil material exposed by mining from the Cretaceous era Coleraine Formation.

Zapsalis is a genus of dromaeosaurine theropod dinosaurs. It is a tooth taxon, often considered dubious because of the fragmentary nature of the fossils, which include teeth but no other remains.

Dimetrodon borealis, formerly known as Bathygnathus borealis, is an extinct species of pelycosaur-grade synapsid that lived about 270 million years ago (Ma) in the Early Middle Permian. A partial maxilla or upper jaw bone from Prince Edward Island in Canada is the only known fossil of Bathygnathus. The maxilla was discovered around 1845 during the course of a well excavation in Spring Brook in the New London area and its significance was recognized by geologists John William Dawson and Joseph Leidy. It was originally described by Leidy in 1854 as the lower jaw of a dinosaur, making it the first purported dinosaur to have been found in Canada, and the second to have been found in all of North America. The bone was later identified as that of a pelycosaur. Although its current classification as a sphenacodontid synapsid was not recognized until after the discovery of its more famous relative Dimetrodon in the 1870s, Bathygnathus is notable for being the first discovered sphenacodontid. A 2015 study by the researchers from the University of Toronto Mississauga, Carleton University and the Royal Ontario Museum reclassified the species into the genus Dimetrodon.

Astrodon is a genus of large herbivorous sauropod dinosaur, measuring 20 m (66 ft) in length, 9 m (30 ft) in height and 20 metric tons in body mass. It lived in what is now the eastern United States during the Early Cretaceous period, and fossils have been found in the Arundel Formation, which has been dated through palynomorphs to the Albian about 112 to 110 million years ago.

Dysganus (dis-GANN-us) is a dubious genus of ceratopsian dinosaur from the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. The fossil teeth referred to Dysganus were first collected by Charles Sternberg from the Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana and later described by Edward Drinker Cope. All of the species are now seen as dubious Ceratopsians, though referred material from tyrannosaurids and hadrosaurids were found in New Mexico.

Charles Whitney Gilmore was an American paleontologist who gained renown in the early 20th century for his work on vertebrate fossils during his career at the United States National Museum. Gilmore named many dinosaurs in North America and Mongolia, including the Cretaceous sauropod Alamosaurus, Alectrosaurus, Archaeornithomimus, Bactrosaurus, Brachyceratops, Chirostenotes, Mongolosaurus, Parrosaurus, Pinacosaurus, Styracosaurus ovatus and Thescelosaurus.

Paleontology in Maryland refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maryland. The invertebrate fossils of Maryland are similar to those of neighboring Delaware. For most of the early Paleozoic era, Maryland was covered by a shallow sea, although it was above sea level for portions of the Ordovician and Devonian. The ancient marine life of Maryland included brachiopods and bryozoans while horsetails and scale trees grew on land. By the end of the era, the sea had left the state completely. In the early Mesozoic, Pangaea was splitting up. The same geologic forces that divided the supercontinent formed massive lakes. Dinosaur footprints were preserved along their shores. During the Cretaceous, the state was home to dinosaurs. During the early part of the Cenozoic era, the state was alternatingly submerged by sea water or exposed. During the Ice Age, mastodons lived in the state.

Local paleontology in Washington, D.C., is known primarily for two serendipitously discovered dinosaur fossils. The first was a vertebra from a carnivorous dinosaur nicknamed "Capitalsaurus" that was related to Tyrannosaurus rex. "Capitalsaurus" is the official dinosaur of the District of Columbia; the place it was discovered was named Capitalsaurus Court in its honor and it even has its own local holiday. The second major fossil find was a thighbone from the long-necked sauropod Astrodon. The District of Columbia and Maryland are the only places where Early Cretaceous dinosaur remains are known to have been preserved east of the Mississippi River.

Paleontology in South Carolina refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of South Carolina. Evidence suggests that at least part of South Carolina was covered by a warm, shallow sea and inhabited by trilobites during the Cambrian period. Other than this, little is known about the earliest prehistory of South Carolina because the Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous, Permian, Triassic, and Jurassic, are missing from the state's local rock record. The earliest fossils of South Carolina date back to the Cretaceous, when the state was partially covered by seawater. Contemporary fossils include marine invertebrates and the remains of dinosaur carcasses that washed out to sea. On land, a wide variety of trees grew. Sea levels rose and fell throughout the ensuing Cenozoic era. Local marine life included invertebrates, fish, sharks, whales. The first scientifically accurate identification of vertebrate fossils in North America occurred in South Carolina. In 1725, African slaves digging in a swamp uncovered mammoth teeth, which they recognized as originating from an elephant-like animal.

Paleontology in New Jersey refers to paleontological research in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The state is especially rich in marine deposits.

Paleontology in Connecticut refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Connecticut. Apart from its famous dinosaur tracks, the fossil record in Connecticut is relatively sparse. The oldest known fossils in Connecticut date back to the Triassic period. At the time, Pangaea was beginning to divide and local rift valleys became massive lakes. A wide variety of vegetation, invertebrates and reptiles are known from Triassic Connecticut. During the Early Jurassic local dinosaurs left behind an abundance of footprints that would later fossilize.

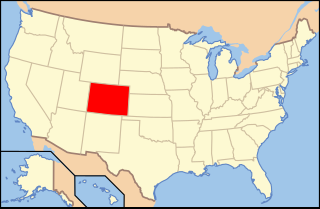

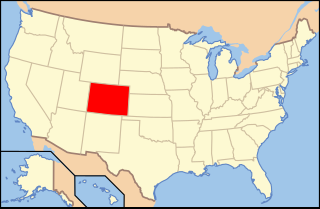

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

Paleontology in the United States refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the United States. Paleontologists have found that at the start of the Paleozoic era, what is now "North" America was actually in the southern hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas. Later the seas were largely replaced by swamps, home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.

The history of paleontology in the United States refers to the developments and discoveries regarding fossils found within or by people from the United States of America. Local paleontology began informally with Native Americans, who have been familiar with fossils for thousands of years. They both told myths about them and applied them to practical purposes. African slaves also contributed their knowledge; the first reasonably accurate recorded identification of vertebrate fossils in the new world was made by slaves on a South Carolina plantation who recognized the elephant affinities of mammoth molars uncovered there in 1725. The first major fossil discovery to attract the attention of formally trained scientists were the Ice Age fossils of Kentucky's Big Bone Lick. These fossils were studied by eminent intellectuals like France's George Cuvier and local statesmen and frontiersman like Daniel Boone, Benjamin Franklin, William Henry Harrison, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington. By the end of the 18th century possible dinosaur fossils had already been found.