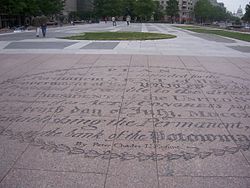

Freedom Plaza in Washington, D.C. in 2005 | |

| Location | Northwest Washington, D.C., U.S. |

|---|---|

Freedom Plaza, originally known as Western Plaza, is an open plaza in Northwest Washington, D.C., United States, located near 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, adjacent to Pershing Park. The plaza features an inlay that partially depicts Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's plan for the City of Washington. The National Park Service administers the Plaza as part of its Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site and coordinates the Plaza's activities. [1]

Contents

The John A. Wilson Building, the seat of the District of Columbia government, faces the plaza, as does the historic National Theatre, which has been visited by every U.S. president since it opened in 1835. [2] [3] Three large hotels are to the north and west. The Old Post Office building, which houses the Waldorf Astoria Washington D.C., is to the southeast. [4]