Related Research Articles

The president of Ireland is the head of state of Ireland and the supreme commander of the Irish Defence Forces.

The Irish Free State was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between the forces of the Irish Republic – the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – and British Crown forces.

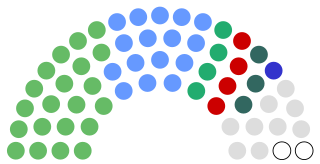

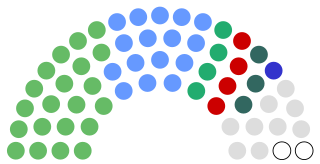

The Oireachtas, sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the bicameral parliament of Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of:

The Constitution of the Irish Free State was adopted by Act of Dáil Éireann sitting as a constituent assembly on 25 October 1922. In accordance with Article 83 of the Constitution, the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 of the British Parliament, which came into effect upon receiving the royal assent on 5 December 1922, provided that the Constitution would come into effect upon the issue of a Royal Proclamation, which was done on 6 December 1922. In 1937 the Constitution of the Irish Free State was replaced by the modern Constitution of Ireland following a referendum.

The Government of the 8th Dáil or the 7th Executive Council was the Executive Council of the Irish Free State formed after the general election held on 24 January 1933. It was led by Fianna Fáil leader Éamon de Valera as President of the Executive Council, who had first taken office in the Irish Free State after the 1932 general election. De Valera had previously served as President of Dáil Éireann, or President of the Republic, from April 1919 to January 1922 during the revolutionary period of the Irish Republic.

The Ninth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1984 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland that allowed for the extension of the right to vote in elections to Dáil Éireann to non-Irish citizens. It was approved by referendum on 14 June 1984, the same day as the European Parliament election, and signed into law on 2 August of the same year.

The Twentieth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2001 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland which provided constitutional recognition of local government and required that local government elections occur at least once in every five years. It was approved by referendum on 11 June 1999 and signed into law on 23 June of the same year. The referendum was held the same day as the local and European Parliament elections.

The Twenty-first Amendment of the Constitution Act 2001 is an amendment of the Constitution of Ireland which introduced a constitutional ban on the death penalty and removed all references to capital punishment from the text. It was approved by referendum on 7 June 2001 and signed into law on 27 March 2002. The referendum was held on the same day as referendums on the ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which was also approved, and on the ratification of the Nice Treaty, which was rejected.

The Twenty-third Amendment of the Constitution Act 2001 of the Constitution of Ireland is an amendment that permitted the state to become a party to the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was approved by referendum on 7 June 2001 and signed into law on the 27 March 2002. The referendum was held on the same day as referendums on the prohibition of the death penalty, which was also approved, and on the ratification of the Nice Treaty, which was rejected.

In Ireland, direct elections by universal suffrage are used for the President, the ceremonial head of state; for Dáil Éireann, the house of representatives of the Oireachtas or parliament; for the European Parliament; and for local government. All elections use proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (PR-STV) in constituencies returning three or more members, except that the presidential election and by-elections use the single-winner analogue of STV, elsewhere called instant-runoff voting or the alternative vote. Members of Seanad Éireann, the second house of the Oireachtas, are partly nominated, partly indirectly elected, and partly elected by graduates of particular universities.

The current Constitution of Ireland came into effect on 29 December 1937, repealing and replacing the Constitution of the Irish Free State, having been approved in a national plebiscite on 1 July 1937 with the support of 56.5% of voters in the then Irish Free State. The Constitution was closely associated with Éamon de Valera, the President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State at the time of its approval.

The granting, reserving or withholding of the Royal Assent was one of the key roles, and potentially one of the key powers, possessed by the Governor-General of the Irish Free State. Until it was granted, no bill passed by the Oireachtas could complete its passage of enactment and become law.

Michael Lanigan is a retired Irish company director and Fianna Fáil politician from County Kilkenny. He was a senator from 1977 to 2002, and was noted in the Seanad for his interest in foreign affairs, particularly humanitarian issues and the Palestinian cause.

The Leader of the Seanad is a member of Seanad Éireann appointed by the Taoiseach to direct government business. Since December 2022, the incumbent is Lisa Chambers of Fianna Fáil. The Deputy leader of the Seanad is Regina Doherty of Fine Gael.

An election for 19 of the 60 seats in Seanad Éireann, the Senate of the Irish Free State, was held on 17 September 1925. The election was by single transferable vote, with the entire state forming a single 19-seat electoral district. There were 76 candidates on the ballot paper, whom voters ranked by preference. Of the two main political parties, the larger did not formally endorse any candidates, while the other boycotted the election. Voter turnout was low and the outcome was considered unsatisfactory. Subsequently, senators were selected by the Oireachtas rather than the electorate.

Seanad Éireann is the upper house of the Oireachtas, which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann.

The Convention on the Constitution was established in Ireland in 2012 to discuss proposed amendments to the Constitution of Ireland. More commonly called simply the Constitutional Convention, it met for the first time 1 December 2012 and sat until 31 March 2014. It had 100 members: a chairman; 29 members of the Oireachtas (parliament); four representatives of Northern Ireland political parties; and 66 randomly selected citizens of Ireland.

The Constitution Act 1933 was an Act of the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State amending the Constitution of the Irish Free State and the Constitution of the Irish Free State Act 1922. It removed the Oath of Allegiance required of members of the Oireachtas (legislature) and of non-Oireachtas extern ministers.

The Constitution Act 1936 was an Act of the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State amending the Constitution of the Irish Free State which had been adopted in 1922. It abolished the two university constituencies in Dáil Éireann.

References

- All-Party Oireachtas Committee on the Constitution (1998). The President (PDF). Progress Report. Vol. 3. Dublin: Stationery Office. ISBN 0-7076-6161-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- Sexton, Brendan (1989). Ireland and the crown, 1922–1936: the Governor-Generalship of the Irish Free State. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9780716524489.

- "Constitution of Ireland". Irish Statute Book . Attorney General of Ireland. August 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Oireachtas business

- ↑ Dáil 25 September 1922 p.12

- ↑ Dáil 3 February 1925 v10 p2 c1

- 1 2 3 Dáil 2 June 1937 p.19 cc.1617–30

- ↑ Dáil 9 June 1937 p.17 c.183

- ↑ Dáil 22 April 1954 p.3

- ↑ Dáil 21 January 1976 p.4

- ↑ Dáil 20 October 1981 p.3

- ↑ Dáil 11 February 1981 p.7

- 1 2 Dáil 4 November 1986 p.4

- 1 2 Dáil 29 June 1988 p.14

- ↑ Dáil 25 October 1988 p.4

- ↑ Dáil 18 June 1991 p.3

- ↑ Dáil 25 February 1992 p.6

- ↑ Dáil 8 July 1992 p.77

- 1 2 Dáil 2 March 1994 p.8

- ↑ Dáil 19 February 1991 p.4

- 1 2 Dáil 31 October 1985 p.22

- ↑ Dáil 24 June 1998 p.20

- 1 2 3 Dáil 8 December 1998 p.4

- ↑ Dáil 19 May 1999 p.6

- ↑ Dáil 2 November 1999 p.4

- 1 2 Sub-Committee on Seanad Reform 16 September 2003 p.8

- ↑ Dáil 2 November 2004 p.153

- ↑ Dáil 8 March 2005 p.57

- 1 2 Joint Committee on Arts, Sport, Tourism, Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs 2 March 2005 p.3

- ↑ Dáil 7 June 2006 p.91

- 1 2 3 4 Dáil 20 November 2007 p.3

- 1 2 Dáil 12 December 2007 p.4

- ↑ Dáil 11 March 2009 p.67

- ↑ Dáil 12 January 2011 p.89

- 1 2 3 "Dáil 17 April 1991" . Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Dáil 25 February 2004 p.75

- ↑ Dáil 1 July 2014 Q.97

- ↑ Dáil 10 Nov 2015 p.89

- ↑ Seanad 11 December 1946 p.5 cc.166–167

- 1 2 Select Committee on Health and Children 30 January 2002 p.3

- ↑ Select Committee on Health and Children 21 Mar 2001 p.3

- ↑ Dáil 22 Jun 1990 p.5

- ↑ Seanad 3 December 2002 p.7

- Other

- 1 2 Oireachtas Committee on the Constitution 1998, p.10

- ↑ Constitution of Ireland, Article 40.2.1°

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith, Murray (1999). "No Honours Please, We're Republicans". Irish Student Law Review. Dublin: King's Inns. 7: 112. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 Mohr, Thomas. "British Involvement in the Creation of the First Irish Constitution". Research Repository. School of Law, University College Dublin. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "First Schedule". Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) Act, 1922.

- ↑ Oranmore and Browne, Baron, Geoffrey (30 November 1922). "Irish Free State Constitution Bill". Hansard. UK Parliament. HL Deb vol 52 c159. Retrieved 15 September 2020.; Oranmore and Browne, Baron, Geoffrey (7 March 1923). "Honours Commission's Report". Hansard. UK Parliament. HL Deb vol 53 c277. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ↑ "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". The London Gazette (Supplement to 33007): 1–2. 30 December 1924. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ Ruane, Bláthna (2015). "Régime Change: The Fate of the Senior Crown Judiciary Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty 1921". Irish Jurist. 54: 108, 113. ISSN 0021-1273. JSTOR 26431250.

- ↑ Sexton 1989 pp.127–128

- 1 2 Keogh, Dermot (1995). Ireland and the Vatican: The Politics and Diplomacy of Church-state Relations, 1922-1960. Cork University Press. pp. 94–99. ISBN 9780902561960.

- ↑ Sexton 1989 p.127

- ↑ Sexton 1989 p.128

- 1 2 3 4 Duffy, Jim (4 July 2004). "An honours system? Yes, let's have one". Irish Independent . Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Burns, John (15 November 2005). "Focus: Does Ireland need its own awards?". Sunday Times . Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ Loughlin, James (2007). The British monarchy and Ireland: 1800 to the present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–1. ISBN 978-0-521-84372-0.

- 1 2 Kenny, Mary (8 December 2007). "How about giving an honour to a lavatory attendant who has provided a sparkling convenience to unnamed numbers of tired shoppers in need of relief?". Irish Independent . Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ "Draft Constitution (4th revision: NAI/DT/S10160)". The Origins of the Irish Constitution. Royal Irish Academy. 26 April 1937. pp. 82, Art. 39.2. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 Hood, Susan (1 January 2002). Royal Roots, Republican Inheritance: The Survival of the Office of Arms. Woodfield Press. ISBN 9780953429332.

- ↑ "Office of the Chief Herald". National Library of Ireland. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Termination of the system of Courtesy Recognition as Chief of the Name" (PDF). National Library of Ireland. 13 August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Healy, Alison (29 December 2021). "Plan for 'Irish knighthoods' system fell flat, files from 1991 show". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ Oireachtas Committee on the Constitution 1998, pp.10–12

- ↑ Constitution of Ireland, Article 13, sections 10 and 11.

- ↑ "Taoiseach in Irish honours call". BBC Online . 27 July 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tánaiste announces the Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish Abroad". Dublin: Department of Foreign Affairs. 17 March 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012.

- ↑ "Gradam an Uachtaráin Bill 2015 [Seanad][PMB] (Number 106 of 2015)". Bills. Oireachtas. Retrieved 9 December 2015.; Quinn, Feargal (November 2015). "Gradam an Uachtaráin Bill 2015 [Seanad][PMB] Explanatory Memorandum" (PDF). Oireachtas. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ "Gradam an Uachtaráin Bill 2015". Bills. Oireachtas. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Gradam an Uachtaráin Bill 2023: Second Stage". Seanad Éireann (26th Seanad). Houses of the Oireachtas. 14 June 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ Finn, Christina (13 June 2023). "Honour system that adds 'G.U.' letters after name of awardee would face pushback, says Varadkar". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Anthony Bailey brings further legal complaint for defamation against the Mail on Sunday". anthonybailey.org. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Senator calls for Irish honours system". 25 February 2003. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ "President Obama Names Medal of Freedom Recipients". whitehouse.gov . 30 July 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2015– via National Archives.

- ↑ "About the Association". Association of Papal Orders in Ireland. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ "Marine Awards Scheme". Dublin: Department of Transport. 4 December 2006. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ "Local Government Act, 2001, Section 74". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ Sweeney, Ken (23 September 2010). "Legends of music scene recall their golden era". Irish Independent . Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ Scholes, Kevan; Johnson, Gerry (2001). Exploring public sector strategy. Prentice Hall. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-273-64687-7.

- ↑ Dillon, Willie (19 January 2002). "Last roll of the dice for political board games?". Irish Independent . Retrieved 30 December 2010.

We don't have an honours system in Ireland. In practice, this has become the honours system whereby party worthies are appointed to the boards of state monopolies, state organisations and quangos.

- ↑ Reilly, Jerome (30 April 2006). "Backroom teams to get their medals". Irish Independent . Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ Taskforce on Active Citizenship (March 2007). "Report". p. 19. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ "Honours system planned to reward outstanding citizens". Irish Independent . 22 April 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ Cowen, Brian (3 November 2009). "Questions: Departmental Agencies". Dáil debates. KildareStreet.com. Retrieved 17 October 2017.; Millar, Scott (28 June 2010). "Community groups in crisis". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ↑ "Presidential Distinguished Service Awards". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 24 January 2022.