Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a ruptured appendix include widespread, painful inflammation of the inner lining of the abdominal wall and sepsis.

Bowel obstruction, also known as intestinal obstruction, is a mechanical or functional obstruction of the intestines which prevents the normal movement of the products of digestion. Either the small bowel or large bowel may be affected. Signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, bloating and not passing gas. Mechanical obstruction is the cause of about 5 to 15% of cases of severe abdominal pain of sudden onset requiring admission to hospital.

Interventional radiology (IR) is a medical subspecialty that performs various minimally-invasive procedures using medical imaging guidance, such as x-ray fluoroscopy, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound. IR performs both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures through very small incisions or body orifices. Diagnostic IR procedures are those intended to help make a diagnosis or guide further medical treatment, and include image-guided biopsy of a tumor or injection of an imaging contrast agent into a hollow structure, such as a blood vessel or a duct. By contrast, therapeutic IR procedures provide direct treatment—they include catheter-based medicine delivery, medical device placement, and angioplasty of narrowed structures.

Ischemia or ischaemia is a restriction in blood supply to tissues, causing a shortage of oxygen that is needed for cellular metabolism. Ischemia is generally caused by problems with blood vessels, with resultant damage to or dysfunction of tissue i.e. hypoxia and microvascular dysfunction. It also means local anemia in a given part of a body sometimes resulting from constriction. Ischemia comprises not only insufficiency of oxygen, but also reduced availability of nutrients and inadequate removal of metabolic wastes. Ischemia can be partial or total.

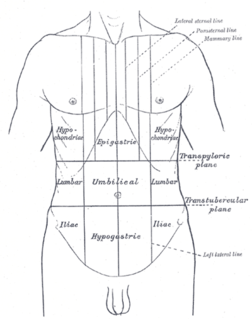

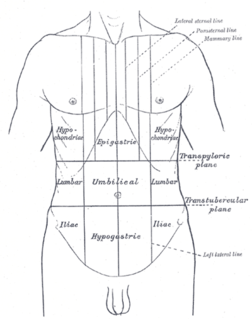

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues.

The mesentery is an organ that attaches the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall in humans and is formed by the double fold of peritoneum. It helps in storing fat and allowing blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves to supply the intestines, among other functions.

A Meckel's diverticulum, a true congenital diverticulum, is a slight bulge in the small intestine present at birth and a vestigial remnant of the omphalomesenteric duct. It is the most common malformation of the gastrointestinal tract and is present in approximately 2% of the population, with males more frequently experiencing symptoms.

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a sudden inflammation of the pancreas. Causes in order of frequency include: 1) a gallstone impacted in the common bile duct beyond the point where the pancreatic duct joins it; 2) heavy alcohol use; 3) systemic disease; 4) trauma; 5) and, in minors, mumps. Acute pancreatitis may be a single event; it may be recurrent; or it may progress to chronic pancreatitis.

Intussusception is a medical condition in which a part of the intestine folds into the section immediately ahead of it. It typically involves the small bowel and less commonly the large bowel. Symptoms include abdominal pain which may come and go, vomiting, abdominal bloating, and bloody stool. It often results in a small bowel obstruction. Other complications may include peritonitis or bowel perforation.

A volvulus is when a loop of intestine twists around itself and the mesentery that supports it, resulting in a bowel obstruction. Symptoms include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, vomiting, constipation, and bloody stool. Onset of symptoms may be rapid or more gradual. The mesentery may become so tightly twisted that blood flow to part of the intestine is cut off, resulting in ischemic bowel. In this situation there may be fever or significant pain when the abdomen is touched.

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a minimally invasive procedure performed in interventional radiology to restrict a tumor's blood supply. Small embolic particles coated with chemotherapeutic drugs are injected selectively through a catheter into an artery directly supplying the tumor. These particles both block the blood supply and induce cytotoxicity, attacking the tumor in several ways.

Intestinal malrotation is a congenital anomaly of rotation of the midgut. It occurs during the first trimester as the fetal gut undergoes a complex series of growth and development. Malrotation can lead to a dangerous complication called volvulus. Malrotation can refer to a spectrum of abnormal intestinal positioning, often including:

Gastrointestinal perforation, also known as ruptured bowel, is a hole in the wall of part of the gastrointestinal tract. The gastrointestinal tract includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Symptoms include severe abdominal pain and tenderness. When the hole is in the stomach or early part of the small intestine the onset of pain is typically sudden while with a hole in the large intestine onset may be more gradual. The pain is usually constant in nature. Sepsis, with an increased heart rate, increased breathing rate, fever, and confusion may occur.

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is a vascular disease of the liver that occurs when a blood clot occurs in the hepatic portal vein, which can lead to increased pressure in the portal vein system and reduced blood supply to the liver. The mortality rate is approximately 1 in 10.

Ischemic colitis is a medical condition in which inflammation and injury of the large intestine result from inadequate blood supply. Although uncommon in the general population, ischemic colitis occurs with greater frequency in the elderly, and is the most common form of bowel ischemia. Causes of the reduced blood flow can include changes in the systemic circulation or local factors such as constriction of blood vessels or a blood clot. In most cases, no specific cause can be identified.

An acute abdomen refers to a sudden, severe abdominal pain. It is in many cases a medical emergency, requiring urgent and specific diagnosis. Several causes need immediate surgical treatment.

Bowel infarction or gangrenous bowel represents an irreversible injury to the intestine resulting from insufficient blood flow. It is considered a medical emergency because it can quickly result in life-threatening infection and death. Any cause of bowel ischemia, the earlier reversible form of injury, may ultimately lead to infarction if uncorrected. The causes of bowel ischemia or infarction include primary vascular causes and other causes of bowel obstruction.

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome is a gastro-vascular disorder in which the third and final portion of the duodenum is compressed between the abdominal aorta (AA) and the overlying superior mesenteric artery. This rare, potentially life-threatening syndrome is typically caused by an angle of 6°–25° between the AA and the SMA, in comparison to the normal range of 38°–56°, due to a lack of retroperitoneal and visceral fat. In addition, the aortomesenteric distance is 2–8 millimeters, as opposed to the typical 10–20. However, a narrow SMA angle alone is not enough to make a diagnosis, because patients with a low BMI, most notably children, have been known to have a narrow SMA angle with no symptoms of SMA syndrome.

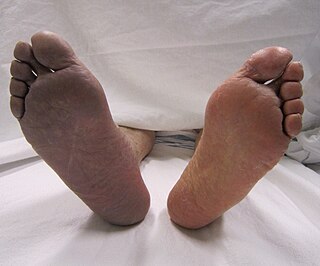

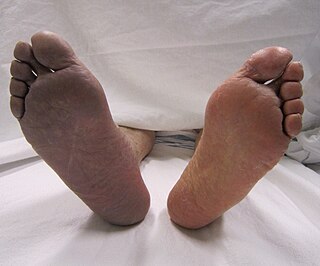

Acute limb ischaemia (ALI) occurs when there is a sudden lack of blood flow to a limb.

Non-occlusive disease (NOD) or Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia (NOMI) is a life-threatening condition including all types of mesenteric ischemia without mesenteric obstruction. It affects mainly elderly patients above 50 years of age who suffer from cardiovascular disease, hepatic, chronic kidney disease or diabetes mellitus. It can be triggered also by a previous cardiac surgery with a consequent heart shock. It represents around 20% of cases of acute mesenteric ischaemia.