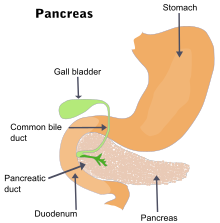

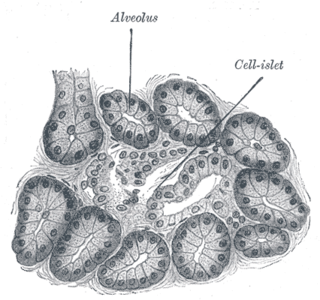

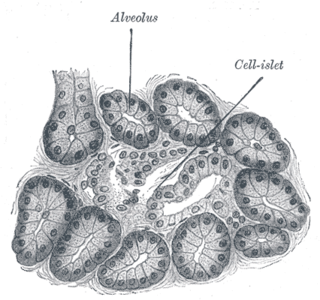

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e., it has both an endocrine and a digestive exocrine function. 99% of the pancreas is exocrine and 1% is endocrine. As an endocrine gland, it functions mostly to regulate blood sugar levels, secreting the hormones insulin, glucagon, somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide. As a part of the digestive system, it functions as an exocrine gland secreting pancreatic juice into the duodenum through the pancreatic duct. This juice contains bicarbonate, which neutralizes acid entering the duodenum from the stomach; and digestive enzymes, which break down carbohydrates, proteins and fats in food entering the duodenum from the stomach.

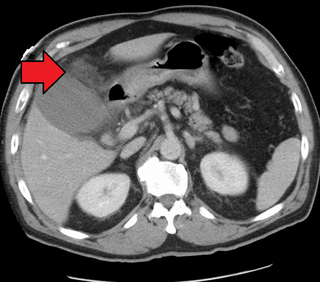

Pancreatitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas is a large organ behind the stomach that produces digestive enzymes and a number of hormones. There are two main types: acute pancreatitis, and chronic pancreatitis.

Cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder. Symptoms include right upper abdominal pain, pain in the right shoulder, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally fever. Often gallbladder attacks precede acute cholecystitis. The pain lasts longer in cholecystitis than in a typical gallbladder attack. Without appropriate treatment, recurrent episodes of cholecystitis are common. Complications of acute cholecystitis include gallstone pancreatitis, common bile duct stones, or inflammation of the common bile duct.

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues. Since the abdomen contains most of the body's vital organs, it can be an indicator of a wide variety of diseases. Given that, approaching the examination of a person and planning of a differential diagnosis is extremely important.

Chronic pancreatitis is a long-standing inflammation of the pancreas that alters the organ's normal structure and functions. It can present as episodes of acute inflammation in a previously injured pancreas, or as chronic damage with persistent pain or malabsorption. It is a disease process characterized by irreversible damage to the pancreas as distinct from reversible changes in acute pancreatitis. Tobacco smoke and alcohol misuse are two of the most frequently implicated causes, and the two risk factors are thought to have a synergistic effect with regards to the development of chronic pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor for the development of pancreatic cancer.

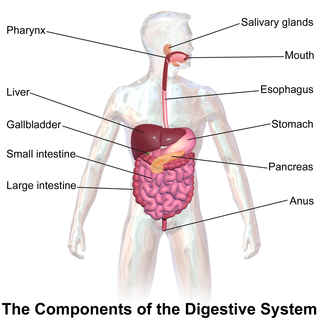

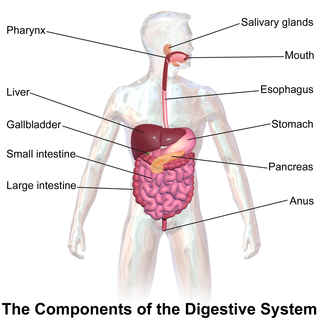

Gastrointestinal diseases refer to diseases involving the gastrointestinal tract, namely the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum; and the accessory organs of digestion, the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

Common bile duct stone, also known as choledocholithiasis, is the presence of gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD). This condition can cause jaundice and liver cell damage. Treatments include choledocholithotomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Pancreatic enzymes, also known as pancreases or pancrelipase and pancreatin, are commercial mixtures of amylase, lipase, protease and lactase. They are used to treat malabsorption syndrome due to certain pancreatic problems. These pancreatic problems may be due to cystic fibrosis, surgical removal of the pancreas, long term pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or MODY 5, among others. The preparation is taken by mouth.

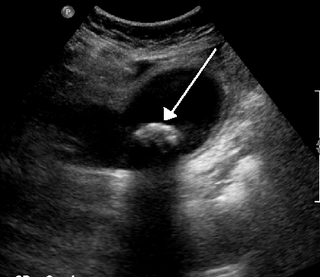

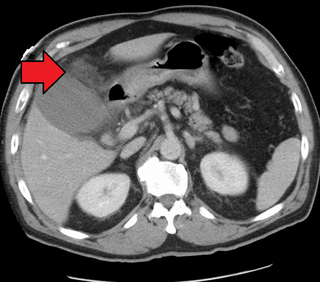

A pancreatic pseudocyst is a circumscribed collection of fluid rich in pancreatic enzymes, blood, and non-necrotic tissue, typically located in the lesser sac of the abdomen. Pancreatic pseudocysts are usually complications of pancreatitis, although in children they frequently occur following abdominal trauma. Pancreatic pseudocysts account for approximately 75% of all pancreatic masses.

A pancreatic fistula is an abnormal communication between the pancreas and other organs due to leakage of pancreatic secretions from damaged pancreatic ducts. An external pancreatic fistula is one that communicates with the skin, and is also known as a pancreaticocutaneous fistula, whereas an internal pancreatic fistula communicates with other internal organs or spaces. Pancreatic fistulas can be caused by pancreatic disease, trauma, or surgery.

Pancreas divisum is a congenital anomaly in the anatomy of the ducts of the pancreas in which a single pancreatic duct is not formed, but rather remains as two distinct dorsal and ventral ducts. Most individuals with pancreas divisum remain without symptoms or complications. A minority of people with pancreatic divisum may develop episodes of abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting due to acute or chronic pancreatitis. The presence of pancreas divisum is usually identified with cross sectional diagnostic imaging, such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). In some cases, it may be detected intraoperatively. If no symptoms or complications are present, then treatment is not necessary. However, if there is recurrent pancreatitis, then a sphincterotomy of the minor papilla may be indicated.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) is the inability to properly digest food due to a lack or reduction of digestive enzymes made by the pancreas. EPI can occur in humans and is prevalent in many conditions such as cystic fibrosis, Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, different types of pancreatitis, multiple types of diabetes mellitus, advanced renal disease, older adults, celiac disease, IBS-D, IBD, HIV, alcohol-related liver disease, Sjogren syndrome, tobacco use, and use of somatostatin analogues.

Pancreatic diseases are diseases that affect the pancreas, an organ in most vertebrates and in humans and other mammals located in the abdomen. The pancreas plays a role in the digestive and endocrine system, producing enzymes which aid the digestion process and the hormone insulin, which regulates blood sugar levels. The most common pancreatic disease is pancreatitis, an inflammation of the pancreas which could come in acute or chronic form. Other pancreatic diseases include diabetes mellitus, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, cystic fibrosis, pseudocysts, cysts, congenital malformations, tumors including pancreatic cancer, and hemosuccus pancreaticus.

Biliary colic, also known as symptomatic cholelithiasis, a gallbladder attack or gallstone attack, is when a colic occurs due to a gallstone temporarily blocking the cystic duct. Typically, the pain is in the right upper part of the abdomen, and can be severe. Pain usually lasts from 15 minutes to a few hours. Often, it occurs after eating a heavy meal, or during the night. Repeated attacks are common. Cholecystokinin - a gastrointestinal hormone - plays a role in the colic, as following the consumption of fatty meals, the hormone triggers the gallbladder to contract, which may expel stones into the duct and temporarily block it until being successfully passed.

The Ranson criteria form a clinical prediction rule for predicting the prognosis and mortality risk of acute pancreatitis. They were introduced in 1974 by the English-American pancreatic expert and surgeon Dr. John Ranson (1938–1995).

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction refers to a group of functional disorders leading to abdominal pain due to dysfunction of the Sphincter of Oddi: functional biliary sphincter of Oddi and functional pancreatic sphincter of Oddi disorder. The sphincter of Oddi is a sphincter muscle, a circular band of muscle at the bottom of the biliary tree which controls the flow of pancreatic juices and bile into the second part of the duodenum. The pathogenesis of this condition is recognized to encompass stenosis or dyskinesia of the sphincter of Oddi ; consequently the terms biliary dyskinesia, papillary stenosis, and postcholecystectomy syndrome have all been used to describe this condition. Both stenosis and dyskinesia can obstruct flow through the sphincter of Oddi and can therefore cause retention of bile in the biliary tree and pancreatic juice in the pancreatic duct.

Pancreatitis is a common condition in cats and dogs. Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas that can occur in two very different forms. Acute pancreatitis is sudden, while chronic pancreatitis is characterized by recurring or persistent form of pancreatic inflammation. Cases of both can be considered mild or severe. It is currently undecided whether chronic pancreatitis is a distinct disease or a form of acute pancreatitis. Other forms such as auto-immune and hereditary pancreatitis are presumed to occur but there existence has not been proven.

Pancreatic abscess is a late complication of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, occurring more than 4 weeks after the initial attack. A pancreatic abscess is a collection of pus resulting from tissue necrosis, liquefaction, and infection. It is estimated that approximately 3% of the patients with acute pancreatitis will develop an abscess.

A pancreatic injury is some form of trauma sustained by the pancreas. The injury can be sustained through either blunt forces, such as a motor vehicle accident, or penetrative forces, such as that of a gunshot wound. The pancreas is one of the least commonly injured organs in abdominal trauma.

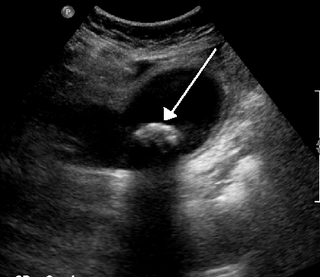

A pancreatic cyst is a fluid filled sac within the pancreas. The prevalence of pancreatic cysts is 2-15% based on imaging studies, but the prevalence may be as high as 50% based on autopsy series. Most pancreatic cysts are benign and the risk of malignancy is 0.5-1.5%. Pancreatic pseudocysts and serous cystadenomas are considered benign pancreatic cysts with a risk of malignancy of 0%.