| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Hydra, Hyzyd, Isovit, others |

| Other names | isonicotinic acid hydrazide, isonicotinyl hydrazine, INH, INAH, INHA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682401 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | Very low (0–10%) |

| Metabolism | liver; CYP450: 2C19, 3A4 inhibitor |

| Elimination half-life | 0.5–1.6h (fast acetylators), 2-5h (slow acetylators) |

| Excretion | urine (primarily), feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.195 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H7N3O |

| Molar mass | 137.142 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Isoniazid, also known as isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH), is an antibiotic used for the treatment of tuberculosis. For active tuberculosis, it is often used together with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either streptomycin or ethambutol. It may also be used for atypical types of mycobacteria, such as M. avium , M. kansasii , and M. xenopi . It is usually taken by mouth, but may be used by injection into muscle.

Contents

- Medical uses

- Tuberculosis

- Non-tuberculous mycobacteria

- Special populations

- History

- Synthesis

- Discovery of anti-TB activity

- Elucidation of mechanism of action

- Modern usage

- Adverse effects

- Side effects

- Drug interactions

- Mechanism of action

- Metabolism

- Overdose

- Preparation

- Brand names

- Other uses

- Chromatography

- References

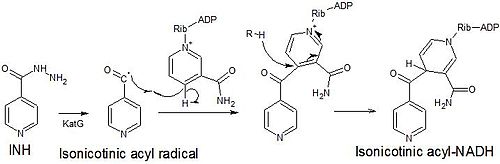

Isoniazid is a prodrug that, when activated by catalase-peroxidase KatG, generates adducts and radicals that inhibits the formation of the mycobacterial cell wall. Side effects in those treated with isoniazid include vitamin B6 deficiency, liver toxicity, peripheral neuropathy, and a reduction in blood cell production. Mutations in the ahpC, inhA, kasA, katG, genes of M. tuberculosis may result in isoniazid resistance.

Although first synthesized in 1912, the anti-tuberculosis activity of isoniazid was not discovered until the 1940s. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines and is available as a generic medication.