A black hole is a region of spacetime wherein gravity is so strong that no matter or electromagnetic energy can escape it. Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can deform spacetime to form a black hole. The boundary of no escape is called the event horizon. A black hole has a great effect on the fate and circumstances of an object crossing it, but it has no locally detectable features according to general relativity. In many ways, a black hole acts like an ideal black body, as it reflects no light. Quantum field theory in curved spacetime predicts that event horizons emit Hawking radiation, with the same spectrum as a black body of a temperature inversely proportional to its mass. This temperature is of the order of billionths of a kelvin for stellar black holes, making it essentially impossible to observe directly.

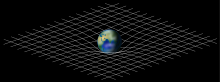

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics. General relativity generalizes special relativity and refines Newton's law of universal gravitation, providing a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time, or four-dimensional spacetime. In particular, the curvature of spacetime is directly related to the energy and momentum of whatever present matter and radiation. The relation is specified by the Einstein field equations, a system of second-order partial differential equations.

In general relativity, a naked singularity is a hypothetical gravitational singularity without an event horizon.

The following is a timeline of gravitational physics and general relativity.

In Einstein's theory of general relativity, the Schwarzschild metric is an exact solution to the Einstein field equations that describes the gravitational field outside a spherical mass, on the assumption that the electric charge of the mass, angular momentum of the mass, and universal cosmological constant are all zero. The solution is a useful approximation for describing slowly rotating astronomical objects such as many stars and planets, including Earth and the Sun. It was found by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916.

The Kerr metric or Kerr geometry describes the geometry of empty spacetime around a rotating uncharged axially symmetric black hole with a quasispherical event horizon. The Kerr metric is an exact solution of the Einstein field equations of general relativity; these equations are highly non-linear, which makes exact solutions very difficult to find.

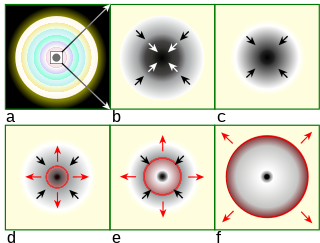

Gravitational collapse is the contraction of an astronomical object due to the influence of its own gravity, which tends to draw matter inward toward the center of gravity. Gravitational collapse is a fundamental mechanism for structure formation in the universe. Over time an initial, relatively smooth distribution of matter, after sufficient accretion, may collapse to form pockets of higher density, such as stars or black holes.

The Shapiro time delay effect, or gravitational time delay effect, is one of the four classic Solar System tests of general relativity. Radar signals passing near a massive object take slightly longer to travel to a target and longer to return than they would if the mass of the object were not present. The time delay is caused by time dilation, which increases the time it takes light to travel a given distance from the perspective of an outside observer. In a 1964 article entitled Fourth Test of General Relativity, Irwin Shapiro wrote:

Because, according to the general theory, the speed of a light wave depends on the strength of the gravitational potential along its path, these time delays should thereby be increased by almost 2×10−4 sec when the radar pulses pass near the sun. Such a change, equivalent to 60 km in distance, could now be measured over the required path length to within about 5 to 10% with presently obtainable equipment.

Richard Chace Tolman was an American mathematical physicist and physical chemist who made many contributions to statistical mechanics and theoretical cosmology. He was a professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

In theoretical physics, Nordström's theory of gravitation was a predecessor of general relativity. Strictly speaking, there were actually two distinct theories proposed by the Finnish theoretical physicist Gunnar Nordström, in 1912 and 1913 respectively. The first was quickly dismissed, but the second became the first known example of a metric theory of gravitation, in which the effects of gravitation are treated entirely in terms of the geometry of a curved spacetime.

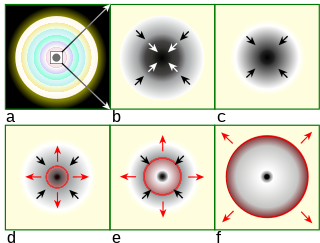

In metric theories of gravitation, particularly general relativity, a static spherically symmetric perfect fluid solution is a spacetime equipped with suitable tensor fields which models a static round ball of a fluid with isotropic pressure.

The Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit is an upper bound to the mass of cold, non-rotating neutron stars, analogous to the Chandrasekhar limit for white dwarf stars. Stars more massive than the TOV limit collapse into a black hole. The original calculation in 1939, which neglected complications such as nuclear forces between neutrons, placed this limit at approximately 0.7 solar masses (M☉). Later, more refined analyses have resulted in larger values.

In astrophysics, the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equation constrains the structure of a spherically symmetric body of isotropic material which is in static gravitational equilibrium, as modeled by general relativity. The equation is

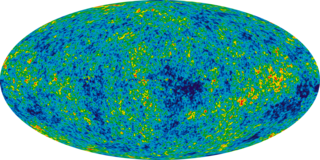

In physics, the Lemaître–Tolman metric, also known as the Lemaître–Tolman–Bondi metric or the Tolman metric, is a Lorentzian metric based on an exact solution of Einstein's field equations; it describes an isotropic and expanding universe which is not homogeneous, and is thus used in cosmology as an alternative to the standard Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric to model the expansion of the universe. It has also been used to model a universe which has a fractal distribution of matter to explain the accelerating expansion of the universe. It was first found by Georges Lemaître in 1933 and Richard Tolman in 1934 and later investigated by Hermann Bondi in 1947.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to black holes:

The Belinski–Zakharov (inverse) transform is a nonlinear transformation that generates new exact solutions of the vacuum Einstein's field equation. It was developed by Vladimir Belinski and Vladimir Zakharov in 1978. The Belinski–Zakharov transform is a generalization of the inverse scattering transform. The solutions produced by this transform are called gravitational solitons (gravisolitons). Despite the term 'soliton' being used to describe gravitational solitons, their behavior is very different from other (classical) solitons. In particular, gravitational solitons do not preserve their amplitude and shape in time, and up to June 2012 their general interpretation remains unknown. What is known however, is that most black holes are special cases of gravitational solitons.

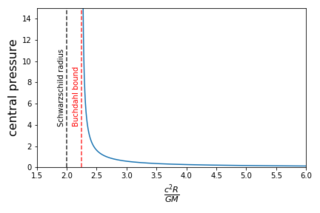

In Einstein's theory of general relativity, the interior Schwarzschild metric is an exact solution for the gravitational field in the interior of a non-rotating spherical body which consists of an incompressible fluid and has zero pressure at the surface. This is a static solution, meaning that it does not change over time. It was discovered by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916, who earlier had found the exterior Schwarzschild metric.

A shell collapsar is a hypothetical compact astrophysical object, which might constitute an alternative explanation for observations of astronomical black hole candidates. It is a collapsed star that resembles a black hole, but is formed without a point-like central singularity and without an event horizon. The model of the shell collapsar was first proposed by Trevor W. Marshall and allows the formation of neutron stars beyond the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit of 0.7 M☉.

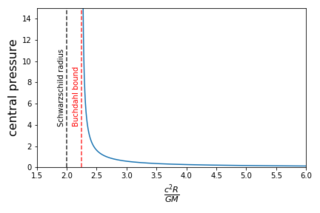

In general relativity, Buchdahl's theorem, named after Hans Adolf Buchdahl, makes more precise the notion that there is a maximal sustainable density for ordinary gravitating matter. It gives an inequality between the mass and radius that must be satisfied for static, spherically symmetric matter configurations under certain conditions. In particular, for areal radius , the mass must satisfy