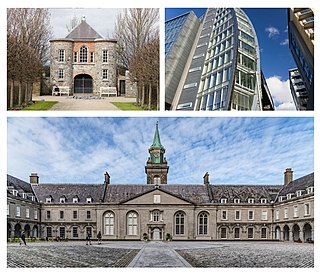

Leinster House is the seat of the Oireachtas, the parliament of Ireland. Originally, it was the ducal palace of the Dukes of Leinster. Since 1922, it has been a complex of buildings of which the former ducal palace is the core, which house Oireachtas Éireann, its members and staff. The most recognisable part of the complex, and the "public face" of Leinster House continues to be the former ducal palace at the core of the complex.

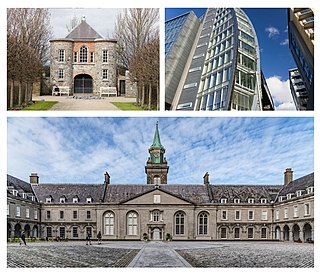

The Royal Hospital Kilmainham in Kilmainham, Dublin, is a former 17th-century hospital at Kilmainham in Ireland. The structure now houses the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Kilmainham is a south inner suburb of Dublin, Ireland, south of the River Liffey and west of the city centre. It is in the city's Dublin 8 postal district.

Events in the year 1911 in Ireland.

Victoria Square, also known as Tarntanyangga, is the central square of five public squares in the Adelaide city centre, South Australia.

HMS Hibernia was a 110-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy. She was launched at Plymouth dockyard on 17 November 1804, and was the only ship built to her draught, designed by Sir John Henslow.

The Sydney central business district (CBD) is the historical and main commercial centre of Sydney. The CBD is Sydney's city centre, or Sydney City, and the two terms are used interchangeably. Colloquially, the CBD or city centre is often referred to simply as "Town" or "the City". The Sydney city centre extends southwards for about 3 km (2 mi) from Sydney Cove, the point of first European settlement in which the Sydney region was initially established.

The Queen Victoria Gardens are Melbourne's memorial to Queen Victoria. Located on 4.8 hectares opposite the Victorian Arts Centre and National Gallery of Victoria, bounded by St Kilda Road, Alexandra Avenue and Linlithgow Avenue.

The Queen Victoria Building is a heritage-listed late-nineteenth-century building located at 429–481 George Street in the Sydney central business district, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Designed by the architect George McRae, the Romanesque Revival building was constructed between 1893 and 1898 and is 30 metres (98 ft) wide by 190 metres (620 ft) long. The domes were built by Ritchie Brothers, a steel and metal company that also built trains, trams and farm equipment. The building fills a city block bounded by George, Market, York, and Druitt Streets. Designed as a marketplace, it was used for a variety of other purposes, underwent remodelling, and suffered decay until its restoration and return to its original use in the late twentieth century. The property is co-owned by the City of Sydney and Link REIT, and was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 March 2010.

John Henry Foley, often referred to as J. H. Foley, was an Irish sculptor, working in London. He is best known for his statues of Daniel O'Connell in Dublin, and of Prince Albert for the Albert Memorial in London and for a number of works in India.

Sir Edgar Bertram Mackennal, usually known as Bertram Mackennal, was an Australian sculptor and medallist, most famous for designing the coinage and stamps bearing the likeness of George V. He signed his work "BM".

Gustavus Vaughan Brooke, commonly referred to as G. V. Brooke, was an Irish stage actor who enjoyed success in Ireland, England, and Australia.

Daniel Corkery was an Irish politician, writer and academic. He is known as the author of The Hidden Ireland, a 1924 study of the poetry of eighteenth-century Irish language poets in Munster.

The Irish National War Memorial Gardens is an Irish war memorial in Islandbridge, Dublin, dedicated "to the memory of the 49,400 Irish soldiers who gave their lives in the Great War, 1914–1918", out of a total of 206,000 Irishmen who served in the British forces alone during the war.

Events from the year 1847 in Ireland.

Rory O'More Bridge is a road bridge spanning the River Liffey in Dublin, Ireland and joining Watling Street to Ellis Street and the north quays.

Australia's monuments take on many distinct forms, including statues, fountains, natural landmarks and buildings. Whilst some monuments of Australia hold a national significance, many are constructed and maintained by local community groups, and are primarily significant on a local scale. Although Australia's monuments have many roles, including as tourist attractions, their primary purpose is to "safeguard, prolong or preserve social memory into the future". This social memory may relate to anything from colonisation to local industry to sports. The monuments of Australia reflect the nation's social and political history and by memorialising select moments, contribute to shaping how Australian history is told. Although a significant portion of Australia is desert, the population is highly urbanised and the cities contain some noteworthy monuments.

The centenary of the Easter Rising in Dublin, Ireland occurred in 2016. Many events were held throughout the country to mark the occasion.