History

Vorticella was first described by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in a letter dated October 9, 1676. Leeuwenhoek thought that Vorticella had two horns moving like horse ears near the oral part, which turned out to be oral cilia beating to create water flow. [4] In 1755, German miniature painter August Johann Rösel described Vorticella, which was named Hydra convallaria by Linnaeus in 1758. However, in 1767, it was renamed Vorticella convallaria. Otto Friedrich Müller listed 127 species of Vorticella in 1786, but many are now known to actually be other protozoans or rotifers. The definition of Vorticella that is still used today was first given by Ehrenberg in 1838. Since then, 80 more species have been described, although many may be synonyms of earlier species. [5]

Habitat and ecology

Habitats may include moist soil, mud and plant roots. [6] This protozoan is ciliated and is mainly found in fresh water environments. [7] They are known to feed on bacteria and can also form extracellular associations with mosquitoes, nematodes, prawns and tadpoles. [6] Vorticella has been found as an epibiont (attached to the surface of a living substratum when in its sessile stage) of crustaceans, the basibiont. This relationship between the epibiont and basibiont is called epibiosis. [8] Rotifers have been observed to feed on Vorticella. Bacteria may also live attached to the surface of Vorticella cells as epibionts, [5] which in some cases may represent a symbiotic relationship between the ciliate and bacteria. [9]

In an annotation to his poetic work "Temple of Nature" (published posthumously in 1803), Erasmus Darwin relayed an experiment wherein he had observed Vorticella to survive a drying-out once rehydrated. [10]

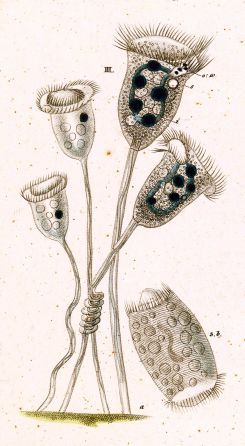

Description

These solitary organisms have globulous bodies which are oval-shaped when contracted. [8] Unfavourable conditions tend to cause Vorticella to change from long and skinny to short and wide. [5] The oral cavity is at one end while the stalk is at the other. [6] The body is 30-40 micrometers in diameter contracted and the stalk is 3-4 micrometers in diameter and 100 micrometers long. [4]

The protoplasm of Vorticella is typically a translucent blue-white colour, but may contain a yellow or green pigment. The food vacuoles may show as a brown or grey colour, but depends on the food eaten. Zoochlorellae, food reserves and waste granules, which are abundant in the cytoplasm, may create the impression that Vorticella is an opaque cell. [5]

Vorticella has a pellicle with striae running parallel around the cell. This pellicle may be decorated with pustules, warty projections, spines or tubercules. Harmless or parasitic bacteria may grow on the body or stalk, appearing as part of the morphology of the cell. [5] Inside, there is a curved, transverse macronucleus and round micronucleus near it.

The similar genus Pseudovorticella is practically indistinguishable from Vorticella under most conditions. The two genera differ in their infraciliature, which can be made visible with silver staining: Pseudovorticella has a mesh-like pattern on the surface of the cell. [11]

Stalk

During its motile form, the free-swimming telotroch appears as a long cylinder, moving quickly and erratically. Stalk materials are secreted in order for the cell to become sessile. Stalk precursors are held in dense granules at the aboral or basal end of the telotroch, which are released as a liquid by exocytosis. That liquid solidifies to form the adhesion pad, stalk matrix and stalk sheath. The stalk will finish growing in several hours. [2]

The stalk is made up of the spasmoneme, a contractile organelle, with rigid rod filaments, batonnets, surrounding it. The coiled spasmoneme and batonnets serve as a molecular spring, so that Vorticella can contract. The cell body can move hundreds of micrometers in milliseconds. The spasmoneme is said to have higher specific power than the engine of the average car. [7]

Feeding

Vorticella has an anterior peristomial lip which is short and narrow. An outward-curving peristomial disc is associated with the peristome. [8] The peristomial disc, which may have ringed ridges or undulations, encloses rows of cilia. The contractile peristomal border closes over the disc and cilia during retraction of Vorticella. [5]

Vorticella is a suspension feeder, and may have reduced or no cytopharynxes, a nonciliated tube for ingestion. There are oral cilia specialized for making water currents, cytostomes in a depression on the cell surface and structures for scraping and filtering food. [1] Oral cilia beat to bring food closer at speeds of 0.1–1 mm/s. [4]

Water flowing inwards brings food through the vestibule, between the inner and outer membranes. The vestibule is a passage for both food entrance and waste exit. The vestibular membranes push the food inwards, where they then congregate in a spindle-shaped food vacuole in the pharynx. Once the food vacuoles leave the non-ciliated pharyngeal tube, they become rounded. When the water flows outwards, contractile vacuoles and full food vacuoles may empty their contents. Contractile vacuoles are located between or beside the macronucleus and vestibule. [5]

The oral cilia contain the adoral zone of membranelles (AZM), which are compound ciliary organelles. The paroral membrane consists of a row of paired cilia. The cytostome has the AZM on one side and the paroral membrane on the other side. [1] As adults, they do not have somatic cilia. [8] In terms of reproduction, Vorticella can undergo binary fission. [1] This occurs when the organism splits into two parts, with the division going along the length of the organism (“The Vorticella” 1885).

Vorticella as pest control

The growth, development and emergence of mosquito larvae are inhibited by Vorticella, resulting in death. The biopolymer glue used for attachment to surfaces may damage sensory systems or pore formation of larvae. Another possibility is that the larvae die by being unable to remain on the surface of the water, thus drowning. Vorticella has for this reason, been explored as a method of biocontrol for mosquitoes, which are vectors of pathogenic, tropical diseases. [6]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.