A digital camera is a camera that captures photographs in digital memory. Most cameras produced today are digital, largely replacing those that capture images on photographic film. Digital cameras are now widely incorporated into mobile devices like smartphones with the same or more capabilities and features of dedicated cameras. High-end, high-definition dedicated cameras are still commonly used by professionals and those who desire to take higher-quality photographs.

Film speed is the measure of a photographic film's sensitivity to light, determined by sensitometry and measured on various numerical scales, the most recent being the ISO system. A closely related ISO system is used to describe the relationship between exposure and output image lightness in digital cameras.

135 film, more popularly referred to as 35 mm film or 35 mm, is a format of photographic film used for still photography. It is a film with a film gauge of 35 mm (1.4 in) loaded into a standardized type of magazine – also referred to as a cassette or cartridge – for use in 135 film cameras. The engineering standard for this film is controlled by ISO 1007 titled '135-size film and magazine'.

A digital camera back is a device that attaches to the back of a camera in place of the traditional negative film holder and contains an electronic image sensor. This lets cameras that were designed to use film take digital photographs. These camera backs are generally expensive by consumer standards and are primarily built to be attached on medium- and large-format cameras used by professional photographers.

The Nikon D2X is a 12.4-megapixel professional digital single-lens reflex camera (DSLR) that Nikon Corporation announced on September 16, 2004. The D2X was the high-resolution flagship in Nikon's DSLR line until June 2006 when it was supplanted by the D2Xs and, in time, the Nikon D3 range, Nikon D4 range and Nikon D5 — the latter three using a FX full-format sensor.

A digital single-lens reflex camera is a digital camera that combines the optics and the mechanisms of a single-lens reflex camera with a digital imaging sensor.

The Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n is a 13.5 megapixel full-frame 35mm digital SLR produced as a collaboration between Nikon Corporation and Eastman Kodak. It was an improved version of the Kodak Professional DCS Pro 14n series, and was based on a modified Nikon N80 film SLR and thus compatible with almost all Nikon F mount lenses. The camera was announced in early 2004 and became available to purchase mid-year. A monochrome variant named Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n m of the camera existed as well.

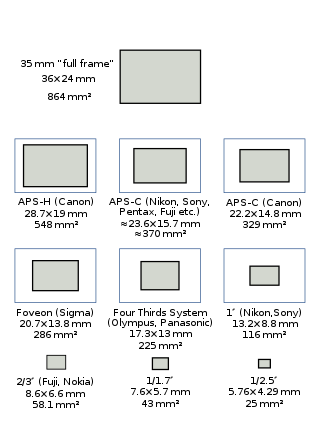

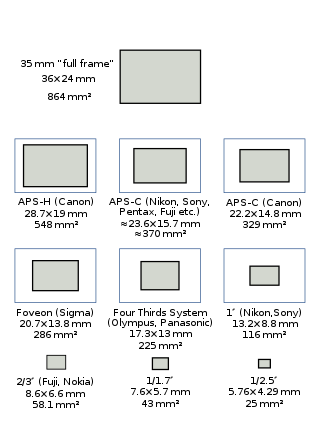

In digital photography, the crop factor, format factor, or focal length multiplier of an image sensor format is the ratio of the dimensions of a camera's imaging area compared to a reference format; most often, this term is applied to digital cameras, relative to 35 mm film format as a reference. In the case of digital cameras, the imaging device would be a digital sensor. The most commonly used definition of crop factor is the ratio of a 35 mm frame's diagonal (43.3 mm) to the diagonal of the image sensor in question; that is, CF=diag35mm / diagsensor. Given the same 3:2 aspect ratio as 35mm's 36 mm × 24 mm area, this is equivalent to the ratio of heights or ratio of widths; the ratio of sensor areas is the square of the crop factor.

The Nikon D1 is a digital single-lens reflex camera (DSLR) made by Nikon Corporation introduced on June 15, 1999. It featured a 2.7-megapixel image sensor, 4.5-frames-per-second continuous shooting, and accepted the full range of Nikon F-mount lenses. The camera body strongly resembled the F5 and had the same general layout of controls, allowing users of Nikon film SLR cameras to quickly become proficient in using the camera. Autofocus speed on the D1 series bodies is extremely fast, even with "screw-driven" AF lenses.

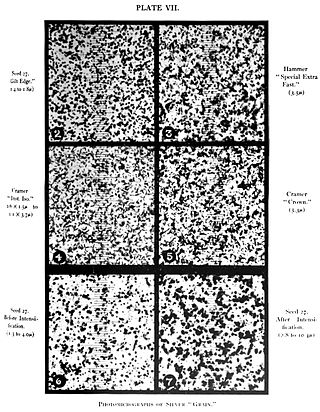

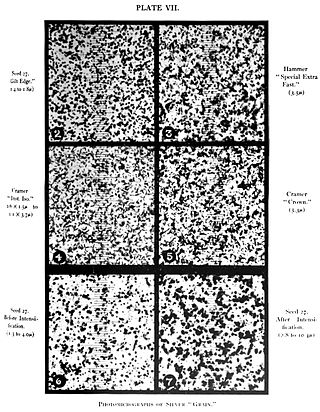

Image noise is random variation of brightness or color information in images, and is usually an aspect of electronic noise. It can be produced by the image sensor and circuitry of a scanner or digital camera. Image noise can also originate in film grain and in the unavoidable shot noise of an ideal photon detector. Image noise is an undesirable by-product of image capture that obscures the desired information. Typically the term “image noise” is used to refer to noise in 2D images, not 3D images.

A full-frame DSLR is a digital single-lens reflex camera (DSLR) with a 35 mm image sensor format. Historically, 35 mm was one of the standard film formats, alongside larger ones, such as medium format and large format. The full-frame DSLR is in contrast to full-frame mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras, and DSLR and mirrorless cameras with smaller sensors, much smaller than a full 35 mm frame. Many digital cameras, both compact and SLR models, use a smaller-than-35 mm frame as it is easier and cheaper to manufacture imaging sensors at a smaller size. Historically, the earliest digital SLR models, such as the Nikon NASA F4 or Kodak DCS 100, also used a smaller sensor.

Digital photography uses cameras containing arrays of electronic photodetectors interfaced to an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to produce images focused by a lens, as opposed to an exposure on photographic film. The digitized image is stored as a computer file ready for further digital processing, viewing, electronic publishing, or digital printing.

Film grain or granularity is the random optical texture of processed photographic film due to the presence of small particles of a metallic silver, or dye clouds, developed from silver halide that have received enough photons. While film grain is a function of such particles it is not the same thing as such. It is an optical effect, the magnitude of which depends on both the film stock and the definition at which it is observed. It can be objectionably noticeable in an over-enlarged film photograph.

In digital photography, the image sensor format is the shape and size of the image sensor.

The Nikon D3 is a 12.0-megapixel professional-grade full frame (35 mm) digital single lens reflex camera (DSLR) announced by the Nikon Corporation on 23 August 2007 along with the Nikon D300 DX format camera. It was Nikon's first full-frame DSLR. The D3, along with the Nikon D3X, was a flagship model in Nikon's line of DSLRs, superseding the D2Hs and D2Xs. It was replaced by the D3S as Nikon's flagship DSLR. The D3, D3X, D3S, D4, D4s, D5, D6, D700, D800, D800Е and Df are the only Nikon FX format DSLRs manufactured in Japan. The D3S was replaced by the D4 in 2012.

The Nikon D300 is a 12.3-megapixel semi-professional DX format digital single-lens reflex camera that Nikon Corporation announced on 23 August 2007 along with the Nikon D3 FX format camera. The D300 was discontinued by Nikon on September 11, 2009, being replaced by the modified Nikon D300S, which was released July 30, 2009. The D300S remained the premier Nikon DX camera until the D7100 was released in early 2013.

Photographic film is a strip or sheet of transparent film base coated on one side with a gelatin emulsion containing microscopically small light-sensitive silver halide crystals. The sizes and other characteristics of the crystals determine the sensitivity, contrast, and resolution of the film.

The Nikon D3S is a 12.1-megapixel professional-grade full frame (35mm) digital single-lens reflex camera (DSLR) announced by Nikon Corporation on 14 October 2009. The D3S is the fourth camera in Nikon's line to feature a full-frame sensor, following the D3, D700 and D3X. It is also Nikon's first full-frame camera to feature HD (720p/30) video recording. While it retains the same number of pixels as its predecessor, the imaging sensor has been completely redesigned. Nikon claims improved ultra-high image sensor sensitivity with up to ISO 102400, HD movie capability for extremely low-lit situations, image sensor cleaning, optimized workflow speed, improved autofocus and metering, enhanced built-in RAW processor, quiet shutter-release mode, up to 4,200 frames per battery charge and other changes compared with the D3. It was replaced by the D4 as Nikon's high speed flagship DSLR.

The Nikon D3200 is a 24.2-megapixel DX format DSLR Nikon F-mount camera officially launched by Nikon on April 19, 2012. It is marketed as an entry-level DSLR camera for beginners and experienced DSLR hobbyists who are ready for more advanced specs and performance.

The Nikon D810 is a 36.3-megapixel professional-grade full-frame digital single-lens reflex camera produced by Nikon. The camera was officially announced in June 2014, and became available in July 2014.