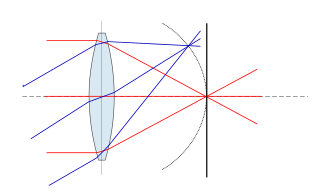

In optics, aberration is a property of optical systems, such as lenses, that causes light to be spread out over some region of space rather than focused to a point. Aberrations cause the image formed by a lens to be blurred or distorted, with the nature of the distortion depending on the type of aberration. Aberration can be defined as a departure of the performance of an optical system from the predictions of paraxial optics. In an imaging system, it occurs when light from one point of an object does not converge into a single point after transmission through the system. Aberrations occur because the simple paraxial theory is not a completely accurate model of the effect of an optical system on light, rather than due to flaws in the optical elements.

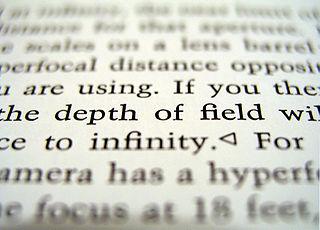

The depth of field (DOF) is the distance between the nearest and the farthest objects that are in acceptably sharp focus in an image captured with a camera. See also the closely related depth of focus.

In optics, the numerical aperture (NA) of an optical system is a dimensionless number that characterizes the range of angles over which the system can accept or emit light. By incorporating index of refraction in its definition, NA has the property that it is constant for a beam as it goes from one material to another, provided there is no refractive power at the interface. The exact definition of the term varies slightly between different areas of optics. Numerical aperture is commonly used in microscopy to describe the acceptance cone of an objective, and in fiber optics, in which it describes the range of angles within which light that is incident on the fiber will be transmitted along it.

In optics, the aperture of an optical system is a hole or an opening that primarily limits light propagated through the system. More specifically, the entrance pupil as the front side image of the aperture and focal length of an optical system determine the cone angle of a bundle of rays that comes to a focus in the image plane.

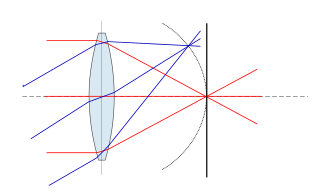

The focal length of an optical system is a measure of how strongly the system converges or diverges light; it is the inverse of the system's optical power. A positive focal length indicates that a system converges light, while a negative focal length indicates that the system diverges light. A system with a shorter focal length bends the rays more sharply, bringing them to a focus in a shorter distance or diverging them more quickly. For the special case of a thin lens in air, a positive focal length is the distance over which initially collimated (parallel) rays are brought to a focus, or alternatively a negative focal length indicates how far in front of the lens a point source must be located to form a collimated beam. For more general optical systems, the focal length has no intuitive meaning; it is simply the inverse of the system's optical power.

An f-number is a measure of the light-gathering ability of an optical system such as a camera lens. It is calculated by dividing the system's focal length by the diameter of the entrance pupil. The f-number is also known as the focal ratio, f-ratio, or f-stop, and it is key in determining the depth of field, diffraction, and exposure of a photograph. The f-number is dimensionless and is usually expressed using a lower-case hooked f with the format f/N, where N is the f-number.

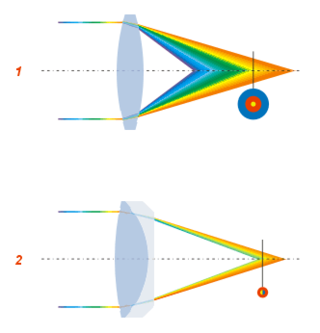

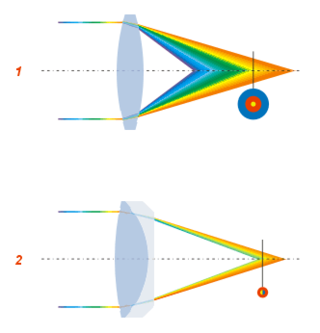

In optics, a circle of confusion (CoC) is an optical spot caused by a cone of light rays from a lens not coming to a perfect focus when imaging a point source. It is also known as disk of confusion, circle of indistinctness, blur circle, or blur spot.

In photography, angle of view (AOV) describes the angular extent of a given scene that is imaged by a camera. It is used interchangeably with the more general term field of view.

An optical telescope is a telescope that gathers and focuses light mainly from the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum, to create a magnified image for direct visual inspection, to make a photograph, or to collect data through electronic image sensors.

Magnification is the process of enlarging the apparent size, not physical size, of something. This enlargement is quantified by a size ratio called optical magnification. When this number is less than one, it refers to a reduction in size, sometimes called de-magnification.

The Scheimpflug principle is a description of the geometric relationship between the orientation of the plane of focus, the lens plane, and the image plane of an optical system when the lens plane is not parallel to the image plane. It is applicable to the use of some camera movements on a view camera. It is also the principle used in corneal pachymetry, the mapping of corneal topography, done prior to refractive eye surgery such as LASIK, and used for early detection of keratoconus. The principle is named after Austrian army Captain Theodor Scheimpflug, who used it in devising a systematic method and apparatus for correcting perspective distortion in aerial photographs, although Captain Scheimpflug himself credits Jules Carpentier with the rule, thus making it an example of Stigler's law of eponymy.

The science of photography is the use of chemistry and physics in all aspects of photography. This applies to the camera, its lenses, physical operation of the camera, electronic camera internals, and the process of developing film in order to take and develop pictures properly.

Depth of focus is a lens optics concept that measures the tolerance of placement of the image plane in relation to the lens. In a camera, depth of focus indicates the tolerance of the film's displacement within the camera and is therefore sometimes referred to as "lens-to-film tolerance".

The following are common definitions related to the machine vision field.

In Gaussian optics, the cardinal points consist of three pairs of points located on the optical axis of a rotationally symmetric, focal, optical system. These are the focal points, the principal points, and the nodal points; there are two of each. For ideal systems, the basic imaging properties such as image size, location, and orientation are completely determined by the locations of the cardinal points; in fact, only four points are necessary: the two focal points and either the principal points or the nodal points. The only ideal system that has been achieved in practice is a plane mirror, however the cardinal points are widely used to approximate the behavior of real optical systems. Cardinal points provide a way to analytically simplify an optical system with many components, allowing the imaging characteristics of the system to be approximately determined with simple calculations.

A photographic lens for which the focus is not adjustable is called a fixed-focus lens or sometimes focus-free. The focus is set at the time of lens design, and remains fixed. It is usually set to the hyperfocal distance, so that the depth of field ranges all the way down from half that distance to infinity, which is acceptable for most cameras used for capturing images of humans or objects larger than a meter.

Tilted plane photography is a method of employing focus as a descriptive, narrative or symbolic artistic device. It is distinct from the more simple uses of selective focus which highlight or emphasise a single point in an image, create an atmospheric bokeh, or miniaturise an obliquely-viewed landscape. In this method the photographer is consciously using the camera to focus on several points in the image at once while de-focussing others, thus making conceptual connections between these points.

In photography, the 35 mm equivalent focal length is a measure of the angle of view for a particular combination of a camera lens and film or image sensor size. The term is popular because in the early years of digital photography, most photographers experienced with interchangeable lenses were most familiar with the 35 mm film format.

For digital image processing, the Focus recovery from a defocused image is an ill-posed problem since it loses the component of high frequency. Most of the methods for focus recovery are based on depth estimation theory. The Linear canonical transform (LCT) gives a scalable kernel to fit many well-known optical effects. Using LCTs to approximate an optical system for imaging and inverting this system, theoretically permits recovery of a defocused image.

Petzval field curvature, named for Joseph Petzval, describes the optical aberration in which a flat object normal to the optical axis cannot be brought properly into focus on a flat image plane. Field curvature can be corrected with the use of a field flattener, designs can also incorporate a curved focal plane like in the case of the human eye in order to improve image quality at the focal surface.

![Nikon 28mm

.mw-parser-output span.fnumber,.mw-parser-output .fnumber-fallback{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;width:max-content}.mw-parser-output span.fnumber::first-letter,.mw-parser-output .fnumber-fallback .first-letter{font-style:italic;font-family:Trebuchet MS,Candara,Georgia,Calibri,Corbel,serif}

f/2.8 lens with markings for the depth of field. The lens is set at the hyperfocal distance for

f/22. The orange mark corresponding to

f/22 is at the infinity mark ([?]). Focus is acceptable from under 0.7 m to infinity. Nikon 28mm lens at hyperfocus.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Nikon_28mm_lens_at_hyperfocus.jpg/220px-Nikon_28mm_lens_at_hyperfocus.jpg)