| Gerstmann syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

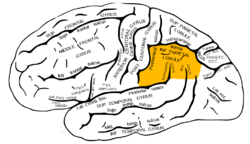

| The inferior parietal lobule, with damage in this area most often associated with Gerstmann syndrome | |

| Specialty | Neurology, neuropsychology |

| Symptoms | Dysgraphia, dyscalculia, finger agnosia, left-right disorientation, constructional apraxia, aphasia |

| Causes | Idiopathic, stroke, dementia |

Gerstmann syndrome is a neurological disorder that is characterized by a constellation of symptoms [1] that suggests the presence of a lesion usually near the junction of the temporal and parietal lobes at or near the angular gyrus. Gerstmann syndrome is typically associated with damage to the inferior parietal lobule of the dominant hemisphere. It is classically considered a left-hemisphere disorder, although right-hemisphere damage has also been associated with components of the syndrome. [2]

Contents

- Symptoms

- Causes

- In adults

- In children

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Prognosis

- See also

- References

- Further reading

- External links

It is named after Jewish Austrian-born American neurologist Josef Gerstmann. [3]