The Fokker F28 Fellowship is a twin-engined, short-range jet airliner designed and built by Dutch aircraft manufacturer Fokker.

Blown flaps, blown wing or jet flaps are powered aerodynamic high-lift devices used on the wings of certain aircraft to improve their low-speed flight characteristics. They use air blown through nozzles to shape the airflow over the rear edge of the wing, directing the flow downward to increase the lift coefficient. There are a variety of methods to achieve this airflow, most of which use jet exhaust or high-pressure air bled off of a jet engine's compressor and then redirected to follow the line of trailing-edge flaps.

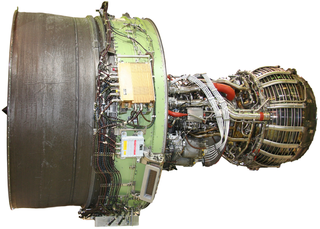

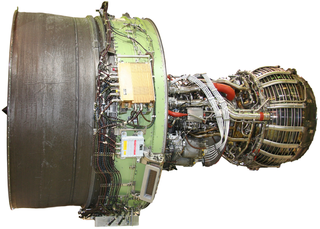

The General Electric GEnx is an advanced dual rotor, axial flow, high-bypass turbofan jet engine in production by GE Aerospace for the Boeing 747-8 and 787. The GEnx succeeded the CF6 in GE's product line.

Bleed air in aerospace engineering is compressed air taken from the compressor stage of a gas turbine, upstream of its fuel-burning sections. Automatic air supply and cabin pressure controller (ASCPC) valves bleed air from low or high stage engine compressor sections; low stage air is used during high power setting operation, and high stage air is used during descent and other low power setting operations. Bleed air from that system can be utilized for internal cooling of the engine, cross-starting another engine, engine and airframe anti-icing, cabin pressurization, pneumatic actuators, air-driven motors, pressurizing the hydraulic reservoir, and waste and water storage tanks. Some engine maintenance manuals refer to such systems as "customer bleed air".

De-icing is the process of removing snow, ice or frost from a surface. Anti-icing is the application of chemicals that not only de-ice but also remain on a surface and continue to delay the reformation of ice for a certain period of time, or prevent adhesion of ice to make mechanical removal easier.

USAir Flight 405 was a regularly scheduled domestic passenger flight between LaGuardia Airport in Queens, New York City, New York, and Cleveland, Ohio. On March 22, 1992, a USAir Fokker F28, registration N485US, flying the route, crashed in poor weather in a partially inverted position in Flushing Bay, shortly after liftoff from LaGuardia. The undercarriage lifted off from the runway, but the airplane failed to gain lift, flying only several meters above the ground. The aircraft then veered off the runway and hit several obstructions before coming to rest in Flushing Bay, just beyond the end of the runway. Of the 51 people on board, 27 were killed, including the captain and a member of the cabin crew.

Air Ontario Flight 1363 was a scheduled Air Ontario passenger flight which crashed near Dryden, Ontario, Canada, on 10 March 1989 shortly after takeoff from Dryden Regional Airport. The aircraft was a Fokker F28-1000 Fellowship twin jet. It crashed after only 49 seconds because it was not able to attain sufficient altitude to clear the trees beyond the end of the runway, due to a buildup of ice and snow on the wings.

In aeronautics, icing is the formation of water ice on an aircraft. Icing has resulted in numerous fatal accidents in aviation history. Ice accretion and accumulation can affect the external surfaces of an aircraft – in which case it is referred to as airframe icing – or the engine, resulting in carburetor icing, air inlet icing or more generically engine icing. These phenomena may possibly but do not necessarily occur together.

Atmospheric icing occurs in the atmosphere when water droplets suspended in air freeze on objects they come in contact with. It is not the same as freezing rain, which is caused directly by precipitation.

A deicing boot is a type of ice protection system installed on aircraft surfaces to permit a mechanical deicing in flight. Such boots are generally installed on the leading edges of wings and control surfaces as these areas are most likely to accumulate ice which could severely affect the aircraft's performance.

American Eagle Flight 4184, officially operating as Simmons Airlines Flight 4184, was a scheduled domestic passenger flight from Indianapolis, Indiana, to Chicago, Illinois, United States. On October 31, 1994, the ATR 72 performing this route flew into severe icing conditions, lost control and crashed into a field, killing all 68 people on board in the high-speed impact.

The Cessna Citation II models are light corporate jets built by Cessna as part of the Citation family. Stretched from the Citation I, the Model 550 was announced in September 1976, first flew on January 31, 1977, and was certified in March 1978. The II/SP is a single pilot version, the improved S/II first flew on February 14, 1984 and the Citation Bravo, a stretched S/II with new avionics and more powerful P&WC PW530A turbofans, first flew on April 25, 1995. The United States Navy adopted a version of the S/II as the T-47A. Production ceased in 2006 after 1,184 of all variants were delivered.

In ground deicing of aircraft, aircraft de-icing fluid (ADF), aircraft de-icer and anti-icer fluid (ADAF) or aircraft anti-icing fluid (AAF) are commonly used for both commercial and general aviation. Environmental concerns include increased salinity of groundwater where de-icing fluids are discharged into soil, and toxicity to humans and other mammals.

The Cessna CitationJet/CJ/M2 are a series of light business jets built by Cessna, and are part of the Citation family. Launched in October 1989, the first flight of the Model 525 was on April 29, 1991. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification was awarded on October 16, 1992, and the first aircraft was delivered on March 30, 1993. The CJ series are powered by two Williams FJ44 engines; the design uses the Citation II's forward fuselage with a new carry-through section wing and a T-tail. The original CitationJet model has been updated into the CJ1/CJ1+/M2 variants; additionally, the CJ1 was stretched into the CJ2/CJ2+ which was built between 2000 and 2016. The design was then further developed into the CJ3/CJ3+, built from December 2004 to present, and finally into the CJ4 which has been built since 2010. By June 2017, 2,000 of all variants had been delivered.

Aircraft systems are those required to operate an aircraft efficiently and safely. Their complexity varies with the type of aircraft.

The 22 January 1971 Surgut Aeroflot Antonov An-12 crash occurred when an Aeroflot Antonov An-12B, registered CCCP-11000, flying from Omsk Tsentralny Airport, in the Soviet Union's (RSFSR) on 22 January 1971, crashed 15 km (9.3 mi) short of the runway on approach to Surgut International Airport, Surgut, RSFSR. An investigation found the aircraft's ice protection system was ineffective because the engine bleed air valves were closed during the flight; ice therefore built up on the aircraft causing it to go out of control.

The Clean Sky Joint Undertaking (CSJU) is a public-private partnership between the European Commission and the European aeronautics industry that coordinates and funds research activities to deliver significantly quieter and more environmentally friendly aircraft. The CSJU manages the Clean Sky Programme (CS) and the Clean Sky 2 Programme (CS2), making it Europe's foremost aeronautical research body.

American Eagle is a brand name for the regional branch of American Airlines, under which six individual regional airlines operate short- and medium-haul feeder flights. Three of these airlines, Envoy Air, Piedmont Airlines, and PSA Airlines, are wholly owned subsidiaries of the American Airlines Group. American Eagle's largest hub is Charlotte Douglas International's Concourse E, which operates over 340 flights per day, making it the largest regional jet operation in the world.

In aviation, ground deicing of aircraft is the process of removing surface frost, ice or frozen contaminants on aircraft surfaces before an aircraft takes off. This prevents even a small amount of surface frost or ice on aircraft surfaces from severely impacting flight performance. Frozen contaminants on surfaces can also break off in flight, damaging engines or control surfaces.

Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217, referred to in the media as the "Miracle on Buffalo Pass", was a scheduled domestic passenger flight from Steamboat Springs, Colorado to Denver that crashed on Buffalo Pass. The aircraft, a de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300, impacted terrain on a gentle slope and was partially buried in snow. All of the 22 passengers and crew survived the impact, but a female passenger died before rescue could arrive, and the captain died of his injuries 3 days after the accident. The investigation determined that the accident was caused by the formation of ice on the wings combined with downdrafts associated with a mountain wave led to the aircraft's loss of control and impact with terrain.