Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah, known as Aga Khan III, was the 48th imam of the Nizari Ism'aili branch of Shia Islam. He was one of the founders and the first permanent president of the All-India Muslim League (AIML). His goal was the advancement of Muslim agendas and the protection of Muslim rights in British India. The League, until the late 1930s, was not a large organisation but represented landed and commercial Muslim interests as well as advocating for British education during the British Raj. There were similarities in Aga Khan's views on education with those of other Muslim social reformers, but the scholar Shenila Khoja-Moolji argues that he also expressed a distinct interest in advancing women's education for women themselves. Aga Khan called on the British Raj to consider Muslims to be a separate nation within India, the famous 'Two Nation Theory'. Even after he resigned as president of the AIML in 1912, he still exerted a major influence on its policies and agendas. He was nominated to represent India at the League of Nations in 1932 and served as President of the 18th Assembly of The League of Nations (1937–1938).

Isma'ilism is a branch or sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sadiq, wherein they differ from the Twelver Shia, who accept Musa al-Kazim, the younger brother of Isma'il, as the true Imām.

Aga Khan is a title held by the Imām of the Nizari Ismāʿīli Shias. Since 1957, the holder of the title has been the 49th Imām, Prince Shah Karim al-Husseini, Aga Khan IV. Aga Khan claims to be a direct descendant of Muhammad, the last prophet according to the religion of Islam.

Nizari Isma'ilism are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent reasoning or ijtihad; pluralism—the acceptance of racial, ethnic, cultural and inter-religious differences; and social justice. Nizaris, along with Twelvers, adhere to the Jaʽfari school of jurisprudence. The Aga Khan, currently Aga Khan IV, is the spiritual leader and Imam of the Nizaris. The global seat of the Ismaili Imamate is in Lisbon, Portugal.

Jamatkhana or Jamat Khana is an amalgamation derived from the Arabic word jama‘a (gathering) and the Persian word khana. It is a term used by some Muslim communities around the world, particularly sufi ones, to a place of gathering. Among some communities of Muslims, the term is often used interchangeably with the Arabic word musallah. The Nizārī Ismā'īlī community uses the term Jama'at Khana to denote their places of worship.

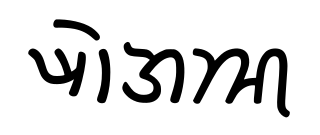

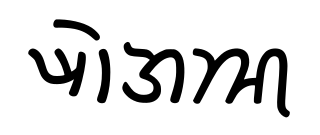

Khojkī, Khojakī, or Khwājā Sindhī, is a script used formerly and almost exclusively by the Khoja community of parts of the Indian subcontinent, including Sindh, Gujarat, and Punjab. However, this script also had a further reach and was used by members of Ismaili communities from Burma to East and South Africa. The Khojki script is one of the earliest forms of written Sindhi. The name "Khojki" is likely derived from the Persian word khoja, which means "master", or "lord".

Aqa Ali Shah, known as Aga Khan II, was the 47th imam of the Nizari Isma'ili Muslims. A member of the Iranian royal family, he became the Imam in 1881. During his lifetime, he helped to better not only his own community, but also the larger Muslim community of India. He was the second Nizari Imam to hold the title Aga Khan.

Pir Sadardin, also known as Pir Sadrudin or Pīr Ṣadr al-Dīn, was a fourteenth-century Shia Ismaili Da'i who founded the Satpanth Tariqa and taught tolerance, perennialism and syncretism of all religions, putting a particular emphasis on the syncretism of Islam and Hinduism.

Ginans are devotional hymns or poems recited by Shia Ismaili Muslims.

Satpanth is a Sanskrit term, given to a diverse group of individuals who follow Pir Sadardin. Pir Sadardin Imamshah Bawa, was a Shia Ismaili Da'i who founded the Satpanth Tariqa around 600 years ago, and taught tolerance, perennialism and syncretism of all religions, putting a particular emphasis on the syncretism of Islam and Hinduism.

The History of Nizari Isma'ilism from the founding of Islam covers a period of over 1400 years. It begins with Muhammad's mission to restore to humanity the universality and knowledge of the oneness of the divine within the Abrahamic tradition, through the final message and what the Shia believe was the appointment of Ali as successor and guardian of that message with both the spiritual and temporal authority of Muhammad through the institution of the Imamate.

Jalāl al-Dīn Ḥasan III (1187–1221), son of Nūr al-Dīn Muḥammad II, was the 25th Nizari Isma'ili Imām. He ruled from 1210 to 1221.

Sadr al-Din may refer to:

The Imamate in Nizari Isma'ili doctrine is a concept in Nizari Isma'ilism which defines the political, religious and spiritual dimensions of authority concerning Islamic leadership over the nation of believers. The primary function of the Imamate is to establish an institution between an Imam who is present and living in the world and his following whereby each are granted rights and responsibilities.

Pir Wazir Ismail Gangji / Varas Ismail Gangji (1788-1883) was an Ismaili Pir, religious leader, Ismaili missionary and social worker from Junagadh, who is also noted for beautiful explanations of some often recited Ginans of Ismaili faith.

Nūram Mubīn is a Gujarati Nizari Ismaili text written by Ali Muhammad Jan Muhammad Chunara (1881–1966) and first published in 1936. It tells of the lives of the Ismaili Imams from the seventh to the twentieth centuries, and is notable for being the first authorized Ismaili history written in an Indian vernacular language.

The Aga Khan Case was an 1866 court decision in the High Court of Bombay by Justice Sir Joseph Arnould that established the authority of the first Aga Khan, Hasan Ali Shah, as the head of the Khoja community of Bombay.

Shams al-Din Muhammad was the 28th imam of the Nizari Isma'ili community. Little is known about his life. He was the first imam to rule after the destruction of the Nizari state by the Mongol Empire, and spent his life hiding his true identity.

Haji Bibi v. His Highness Sir Sultan Mohamed Shah, the Aga Khan, often referred to as the Haji Bibi Case, was a 1908 court case in the Bombay High Court heard by Justice Russell. The case was fundamentally a dispute over the inheritance of the estate of Hasan Ali Shah, a Persian nobleman with the title Aga Khan I and the hereditary leader of the Nizari Ismailis. A number of the properties and other monetary assets had been passed down to Aqa Ali Shah, Aga Khan II and then to his grandson, Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III. The plaintiffs included Haji Bibi who was a widowed granddaughter of Aga Khan I and a few other members of the family that all claimed rights to the wealth. The decision is notable as it confirmed the Aga Khan III's exclusive rights to the assets of his grandfather and to the continued religious offerings by his followers, including some Khojas, as the 48th Imam of the Nizaris.