The Young Turks formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The most powerful organization of the movement, and the most conflated, was the Committee of Union and Progress, though its goals, strategies, and membership continuously morphed throughout Abdul Hamid's reign. By the 1890s, the Young Turks were mainly a loose and contentious network of exiled intelligentsia who made a living by selling their newspapers to secret subscribers.

The Tanzimat was a period of Western influenced reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane in 1839. Its goals were to modernize and consolidate the social and political foundations of the Ottoman Empire in order to secure territorial integrity against internal nationalist movements and external aggressive powers. The reforms encouraged Ottomanism among the diverse ethnic groups of the Empire and attempted to stem the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire.

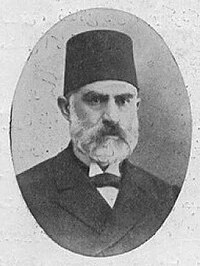

Ahmed Shefik Midhat Pasha was an Ottoman politician, reformist, and statesman. He was the author of the Constitution of the Ottoman Empire.

Mehmed Fuad Pasha, sometimes known as Keçecizade Mehmed Fuad Pasha and commonly known as Fuad Pasha, was an Ottoman administrator and statesman, who is known for his prominent role in the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-19th-century Ottoman Empire, as well as his leadership during the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war in Syria. He represented a modern Ottoman era, given his openness to European-style modernization as well as the reforms he helped to enact.

Koca Mustafa Reşid Paşa was an Ottoman statesman and diplomat, known best as the chief architect behind the imperial Ottoman government reforms known as Tanzimat.

The caliphate of the Ottoman Empire was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty to be the caliphs of Islam in the late medieval and early modern era. During the period of Ottoman expansion, Ottoman rulers claimed caliphal authority after the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by sultan Selim I in 1517 and the abolition of the Mamluk-controlled Abbasid Caliphate. This left Selim as the Defender of the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina and strengthened the Ottoman claim to leadership in the Muslim world.

The Young Ottomans were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the Tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough. The Young Ottomans sought to transform the Ottoman society by preserving the Empire and modernizing it along the European tradition of adopting a constitutional government. Though the Young Ottomans were frequently in disagreement ideologically, they all agreed that the new constitutional government should continue to be at least somewhat rooted in Islam. To emphasize "the continuing and essential validity of Islam as the basis of Ottoman political culture" they attempted to syncretize an Islamic jurisprudence with liberalism and parliamentary democracy. The Young Ottomans sought for new ways to form a government like the European governments, especially the constitution of the Second French Empire. Among the prominent members of this society were writers and publicists such as İbrahim Şinasi, Namık Kemal, Ali Suavi, Ziya Pasha, and Agah Efendi.

Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, also spelled as Mehmed Emin Aali, was a Turkish–Ottoman statesman during the Tanzimat period, best known as the architect of the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856, and for his role in the Treaty of Paris (1856) that ended the Crimean War. From humble origins as the son of a doorkeeper, Âli Pasha rose through the ranks of the Ottoman state and became the Minister of Foreign Affairs for a short time in 1840, and again in 1846. He became Grand Vizier for a few months in 1852. Between 1855 and 1871 he alternated between the two jobs, ultimately holding the position of Foreign Minister seven times and Grand Vizier five times in his lifetime. Âli Pasha was widely regarded as a deft and able statesman, and often credited with preventing an early break-up of the empire.

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) was a period of history of the Ottoman Empire beginning with the Young Turk Revolution and ultimately ending with the empire's dissolution and the founding of the modern state of Turkey.

The Young Turk Revolution was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Constitution, recall the parliament, and schedule an election. Thus began the Second Constitutional Era.

The Second Constitutional Era was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 dissolution of the General Assembly, during the empire's twilight years.

The First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire was the period of constitutional monarchy from the promulgation of the Ottoman constitution of 1876, written by members of the Young Ottomans, that began on 23 December 1876 and lasted until 14 February 1878. These Young Ottomans were dissatisfied by the Tanzimat and instead pushed for a constitutional government similar to that in Europe. The constitutional period started with the dethroning of Sultan Abdulaziz. Abdul Hamid II took his place as Sultan. The era ended with the suspension of the Ottoman Parliament and the constitution by Sultan Abdul Hamid II, with which he restored his own absolute monarchy.

Starting in the 19th century the Ottoman Empire's governing structure slowly transitioned and standardized itself into a Western style system of government, sometimes known as the Imperial Government. Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) initiated this process following the disbandment and massacre of the Janissary corps, at this point a conservative bureaucratic elite, in the Auspicious Incident. A long period of reform known as the Tanzimat period started, which yielded much needed reform to the government and social contract with the multicultural citizens of the empire.

The Constitution of the Ottoman Empire was in effect from 1876 to 1878 in a period known as the First Constitutional Era, and from 1908 to 1922 in the Second Constitutional Era. The first and only constitution of the Ottoman Empire, it was written by members of the Young Ottomans, particularly Midhat Pasha, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. After Abdul Hamid's political downfall in the 31 March Incident, the Constitution was amended to transfer more power from the sultan and the appointed Senate to the popularly-elected lower house: the Chamber of Deputies.

Damat Mehmed Adil Ferid Pasha, known simply as Damat Ferid Pasha, was an Ottoman liberal statesman, who held the office of Grand Vizier, the de facto prime minister of the Ottoman Empire, during two periods under the reign of the last Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI, the first time between 4 March 1919 and 2 October 1919 and the second time between 5 April 1920 and 21 October 1920. Officially, he was brought to the office a total of five times, since his cabinets were recurrently dismissed under various pressures and he had to present new ones. Because of his involvement in the Treaty of Sèvres, his collaboration with the occupying Allied powers, and his readiness to acknowledge atrocities against the Armenians, he was declared a traitor and subsequently a persona non grata in Turkey. He emigrated to Europe at the end of the Greco-Turkish War.

The Freedom and Accord Party was a liberal Ottoman political party active between 1911–1913 and 1918–1919, during the Second Constitutional Era. It was the most significant opposition to Union and Progress in the Chamber of Deputies. The political programme of the party advocated for Ottomanism, government decentralisation, the rights of ethnic minorities, and close relations with Britain. In the post-1918 Ottoman Empire, the party became known for its attempts to suppress and prosecute the CUP. In both of its periods of existence, the party quickly descended into infighting and impotence.

Namık Kemal was an Ottoman writer, poet, democrat, intellectual, reformer, journalist, playwright, and political activist who was influential in the formation of the Young Ottomans and their struggle for governmental reform in the Ottoman Empire during the late Tanzimat period, which would lead to the First Constitutional Era in the Empire in 1876. Kemal was particularly significant for championing the notions of freedom and fatherland in his numerous plays and poems, and his works would have a powerful impact on the establishment of and future reform movements in Turkey, as well as other former Ottoman territories. He is often regarded as being instrumental in redefining Western concepts like natural rights and constitutional government.

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 in the Ottoman Empire and in the Republic of Turkey. The foremost faction of the Young Turks, the CUP instigated the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, which ended absolute monarchy and began the Second Constitutional Era. After an ideological transformation, from 1913 to 1918, the CUP ruled the empire as a dictatorship and committed genocides against the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian peoples as part of a broader policy of ethnic erasure during the late Ottoman period. The CUP and its members have often been referred to as "Young Turks", although the Young Turk movement produced other Ottoman political parties as well. Within the Ottoman Empire its members were known as İttihadcılar ('Unionists') or Komiteciler ('Committeemen').