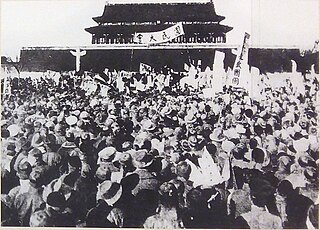

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese cultural and anti-imperialist political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles decision to allow Japan to retain territories in Shandong that had been surrendered by Germany after the Siege of Tsingtao in 1914. The demonstrations sparked nation-wide protests and spurred an upsurge in Chinese nationalism, a shift towards political mobilization away from cultural activities, and a move towards a populist base, away from traditional intellectual and political elites.

The New Culture Movement was a progressivist movement in China in the 1910s and 1920s that criticized classical Chinese ideas and promoted a new Chinese culture based upon progressive, modern ideals like elections and science. Arising out of disillusionment with traditional Chinese culture following the failure of the Republic of China to address China's problems, it featured scholars such as Chen Duxiu, Cai Yuanpei, Chen Hengzhe, Li Dazhao, Lu Xun, Zhou Zuoren, He Dong, Qian Xuantong, Liu Bannong, Bing Xin, and Hu Shih, many classically educated, who led a revolt against Confucianism. The movement was launched by the writers of New Youth magazine, where these intellectuals promoted a new society based on unconstrained individuals rather than the traditional Confucian system.

The People's Republic of China competed at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, United States. It was the first appearance at the Summer Games for the country after its mostly symbolic presence at the Summer Games in 1952 during which the dispute between the Republic of China and the PRC resulted in the former withdrawing all its athletes. After 1952 and until these games, the PRC boycotted the Olympics due to the Taiwan's presence as the Republic of China. In 1984, the Republic of China competed as Chinese Taipei and the PRC competed as China. Due to the then ongoing Sino-Soviet split, China did not participate in the Soviet-led boycott. In the previous games, China participated the United States-led boycott to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, becoming the only communist country to boycott Olympics held by another communist country.

Wang Shenzhi, courtesy name Xintong (信通) or Xiangqing (詳卿), formally Prince Zhongyi of Min (閩忠懿王) and later further posthumously honored as Emperor Taizu of Min (閩太祖), was the founder of Min Kingdom on the modern southeast coastal province of Fujian province in China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of ancient Chinese history. He was from Gushi in modern-day Henan.

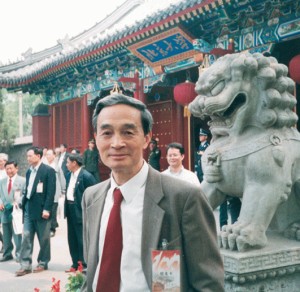

Wang Ruoshui, was a Chinese journalist, political theorist, and philosopher. He was born in Shanghai, and graduated from Peking University with a degree in philosophy. After working at the People's Daily for over three decades, Wang was expelled from the party in 1987 during the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization Campaign, largely due to his long-standing vocal advocacy of Marxist humanism that led to the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign in 1983. After his exile from the party, he went to United States as a visiting scholar to continue his research. Wang was known as a major exponent of Marxist humanism and of Chinese liberalism in the second half on his life.

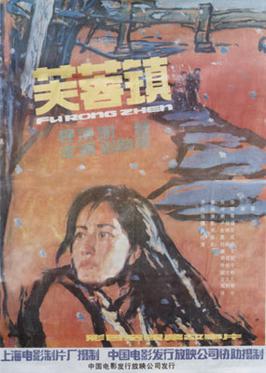

Hibiscus Town is a 1986 Chinese film directed by Xie Jin, based on a novel by the same name written by Gu Hua. The film, a melodrama, follows the life and travails of a young woman who lives through the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution and as such is an example of the "scar drama" genre that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s that detailed life during that period. The film was produced by the Shanghai Film Studio.

The 17th Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), formally the Political Bureau of the 17th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, was elected at the 1st Plenary Session of the 17th Central Committee of the CCP on 22 October 2007 in the aftermath of the 17th National Congress. This electoral term was preceded by the 16th Politburo and succeeded by the 18th. Of the 25 members, nine served in the 17th Politburo Standing Committee.

The 16th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party was in session from 2002 to 2007. It held seven plenary sessions. It was set in motion by the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. The 15th Central Committee preceded it. It was followed by the 17th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

The 12th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party was in session from September 1982 to November 1987. It held seven plenary sessions. It was securely succeeded by the 13th Central Committee.

Three Kingdoms is a 2010 Chinese television series based on the events in the late Eastern Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. The plot is adapted from the 14th century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms and other stories about the Three Kingdoms period. Directed by Gao Xixi, the series had a budget of over 160 million RMB and took five years of pre-production work. Shooting of the series commenced in October 2008, and it was released in China in May 2010.

The Legend and the Hero is a 2007 Chinese television series adapted from the 16th-century novel Fengshen Yanyi written by Xu Zhonglin and Lu Xixing. The first season started airing on CCTV-8 in February 2007. It was followed by a sequel, The Legend and the Hero 2 in 2009.

This is a list of articles in Eastern philosophy.

The Xi Jinping–Li Keqiang Administration of the People's Republic of China began in 2013, when Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang succeeded Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao following the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. It is speculated that Xi will solidify the political power of the CCP general secretary, for the absolute command of the Communist ideology over pragmatic approach, and on the economic front, there will be no liberalization but socialist entrenchment.

The Financial and Economic Affairs Commission of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, commonly called the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, is a commission of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in charge of leading and supervising economic work of both the CCP Central Committee and the State Council. The Commission is generally headed by CCP General Secretary or Premier of the State Council.

1911 Revolution is a Chinese television series based on the events of the Xinhai Revolution, which brought an end to imperial rule in China in 1911. It was first broadcast on CCTV-1 during prime time on 27 September 2011. It was specially produced to mark the 100th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution.