Related Research Articles

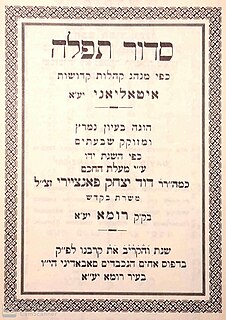

A siddur is a Jewish prayer book containing a set order of daily prayers. The word siddur comes from the Hebrew root ס־ד־ר, meaning 'order.'

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim, are a Jewish diaspora population who coalesced in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE. Their traditional diaspora language is Yiddish, which developed during the Middle Ages after they had moved from Germany and France into Northern Europe and Eastern Europe. For centuries, Ashkenazim in Europe used Hebrew only as a sacred language until the revival of Hebrew as a common language in 20th-century Israel.

Sephardic law and customs are the practice of Judaism by the Sephardim, the descendants of the historic Jewish community of the Iberian Peninsula. Some definitions of "Sephardic" inaccurately include Mizrahi Jews, many of whom follow the same traditions of worship but have different ethno-cultural traditions. Sephardi Rite is not a denomination or movement like Orthodox, Reform, and other Ashkenazi Rite worship traditions. Sephardim thus comprise a community with distinct cultural, juridical and philosophical traditions.

The machzor is the prayer book which is used by Jews on the High Holy Days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Many Jews also make use of specialized machzorim on the three pilgrimage festivals of Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot. The machzor is a specialized form of the siddur, which is generally intended for use in weekday and Shabbat services.

Ashkenazi Hebrew is the pronunciation system for Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew favored for Jewish liturgical use and Torah study by Ashkenazi Jewish practice.

Selichot are Jewish penitential poems and prayers, especially those said in the period leading up to the High Holidays, and on fast days. The Thirteen Attributes of Mercy are a central theme throughout these prayers.

The Ten Days of Repentance are the first ten days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei, usually sometime in the month of September, beginning with the Jewish New Year Rosh Hashanah and ending with the conclusion of Yom Kippur.

Minhag is an accepted tradition or group of traditions in Judaism. A related concept, Nusach, refers to the traditional order and form of the prayers.

In Judaism, Nusach, plural nuschaot or Modern Hebrew nusachim, refers to the exact text of a prayer service; sometimes the English word "rite" is used to refer to the same thing. Texts used by different communities include Nosach Teiman, Nusach Ashkenaz, Nusach Sefard, Nusach Edot Hamizrach, and Nusach Ari. In English, the word nusach means formulate, wording.

Italian Jews or Roman Jews can be used in a broad sense to mean all Jews living in or with roots in Italy, or, in a narrower sense, to mean the Italkim, an ancient community living in Italy since the Ancient Roman era, who use the Italian liturgy as distinct from those Jewish communities in Italy dating from medieval or modern times who use the Sephardic liturgy, the Italian Nusach or the Nusach Ashkenaz.

Mussaf is an additional service that is recited on Shabbat, Yom Tov, Chol Hamoed, and Rosh Chodesh. The service, which is traditionally combined with the Shacharit in synagogues, is considered to be additional to the regular services of Shacharit, Mincha, and Maariv. In contemporary Hebrew, the word may also signify a newspaper supplement.

Tachanun or Taḥanun, also called nefilat apayim, is part of Judaism's morning (Shacharit) and afternoon (Mincha) services, after the recitation of the Amidah, the central part of the daily Jewish prayer services. It is also recited at the end of the Selichot service. It is omitted on Shabbat, Jewish holidays and several other occasions. Most traditions recite a longer prayer on Mondays and Thursdays.

Nusach Sefard, Nusach Sepharad, or Nusach Sfard is the name for various forms of the Jewish siddurim, designed to reconcile Ashkenazi customs with the kabbalistic customs of Isaac Luria. To this end it has incorporated the wording of Nusach Edot haMizrach, the prayer book of Sephardi Jews, into certain prayers. Nusach Sefard is used nearly universally by Hasidim, as well as by some other Ashkenazi Jews but has not gained significant acceptance by Sephardi Jews. Some Hasidic dynasties use their own version of the Nusach Sefard siddur, sometimes with notable divergence between different versions.

Rosh HaShanah is the Jewish New Year. The biblical name for this holiday is Yom Teruah, literally "day of shouting or blasting." It is the first of the Jewish High Holy Days, as specified by Leviticus 23:23–25, that occur in the late summer/early autumn of the Northern Hemisphere. Rosh Hashanah begins a ten-day period of penitence culminating in Yom Kippur, as well as beginning the cycle of autumnal religious festivals running through Sukkot and ending in Shemini Atzeret.

Nusach Ashkenaz is a style of Jewish liturgy conducted by Ashkenazi Jews. It is primarily a way to order and include prayers, and differs from Nusach Sefard and Baladi-rite prayer, and still more from the Sephardic rite proper, in the placement and presence of certain prayers.

Maariv or Maʿariv, also known as Arvit, is a Jewish prayer service held in the evening or night. It consists primarily of the evening Shema and Amidah.

The Palestinian minhag or Palestinian liturgy, as opposed to the Babylonian minhag, refers to the rite and ritual of medieval Palestinian Jewry in relation to the traditional order and form of the prayers.

Italian Nusach, also known as Minhag Italiani, Minhag B'nei Romì, Minhag Lo'ez or Minhag HaLo'azim, is the ancient prayer rite of the indigenous Jews on the Italian peninsula who are not of Ashkenazi or Sephardic origin.

Jews of Catalonia is the Jewish community that lived in the Iberian Peninsula, in the Lands of Catalonia, Valencia and Mallorca until the expulsion of 1492. Its splendor was between the 12th to 14th centuries, in which two important Torah centers flourished in Barcelona and Girona. The Catalan Jewish community developed unique characteristics, which included customs, a prayer rite, and a tradition of its own in issuing legal decisions (Halakhah). Although the Jews of Catalonia had a ritual of prayer and different traditions from those of Sepharad, today they are usually included in the Sephardic Jewish community.

Minhag Ashkenaz is the minhag of the Ashkenazi German Jews. Minhag Ashkenaz was common in Germany, Austria, the Czech lands, and elsewhere in Western Europe, in contrast to the Minhag Polin of the Eastern European Ashkenazi Jews.

References

- ↑ "Kojetin". Jewish Virtual Library . Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ↑ "Vol. 10 No. 20" (PDF). The Beurei Hatefila Library. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ Daniel Goldschimdt, Rosh Hashanah Machzor, page 14 of introduction. In the Middle Ages, the border seems to have been further east.

- ↑ "Bayers and Polanders, "German Jews" and "Polish Jews"". Brandeis University . Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ↑ Daniel Goldschimdt, Rosh Hashanah Machzor, page 14 of introduction. An exception to this is regarding the Selichot rites, where the divisions are subdivided further geographically, see Selichot rites.

- ↑ Hoffman, Rabbi Lawrence A. (2016). Naming God: Avinu Malkeinu— Our Father, Our King. Woodstock: Jewish Lights. p. 264. ISBN 9781580238175.