| Part of a series on |

| Jewish culture |

|---|

|

The Hebrew word for 'symbol' is ot, which, in early Judaism, denoted not only a sign, but also a visible religious token of the relation between God and human.

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish culture |

|---|

|

The Hebrew word for 'symbol' is ot, which, in early Judaism, denoted not only a sign, but also a visible religious token of the relation between God and human.

| Ancient | ||

|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Image | History and usage |

| Menorah |  | Represents the Temple in Jerusalem. Appears in the Emblem of Israel. |

| Four Species |  | Represents the festival of Sukkot. Often an accompaniment of the Menorah. |

| Shofar |  | Represents the High Holy Days. Used as an instrument harkening in the new year in a ceremonial fashion. |

| Intermediate | ||

| Symbol | Image | History and usage |

| Star of David |  | The Star of David, a symbol of Judaism as a religion, and of the Jewish people as a whole. [1] It also thought to be the shield (or at least the emblem on it) of King David. Jewish lore links the symbol to the "Seal of Solomon", the magical signet ring used by King Solomon to control demons and spirits. Jewish lore also links the symbol to a magic shield owned by King David that protected him from enemies. Following Jewish emancipation after the French Revolution, Jewish communities chose the Star of David as their symbol. The star is found on the Flag of Israel. |

| Shin |  | Symbolizes El Shaddai (conventionally translated "God Almighty"), one of the Names of God in Judaism. This symbol is depicted on the ritual objects mezuzah and tefillin, and in the hand gesture of the Priestly Blessing. |

| Tablets of Stone |  | Represents the two tablets on which the Ten Commandments were inscribed at Mount Sinai. |

| Lion of Judah |  | The Tanakh compares the tribes of Judah and Dan to lions: "Judah is a lion's whelp." [2] Often a pair of lions appear as heraldic supporters, especially of the Tablets of Law. |

| Modern | ||

| Symbol | Image | History and usage |

| Chai |  | "Life" in Hebrew. |

| Hamsa |  | In Jewish and other Middle Eastern cultures, the Hamsa represents the hand of God and was reputed to protect against the evil eye. In modern times, it is a common good luck charm and decoration. [3] |

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

Shabbat, the day of rest, is described in the Tanakh as God's sign ("ot") between Him and the Jewish people. [4]

The Torah provides detailed instructions (Exodus 28) for the garments worn by the priests in the Temple. These details became the subject of later symbolic interpretations.

According to Philo: [5] The priest's upper garment symbolized the ether, the blossoms represented the earth, the pomegranates typified running water, and the bells denoted the music of the water. The ephod corresponded to heaven, and the stones on both shoulders to the two hemispheres, one above and the other below the earth. The six names on each of the stones were the six signs of the zodiac, which were denoted also by the twelve names on the breastplate. The miter was the sign of the crown, which exalted the high priest above all earthly kings.

Josephus interpreted as follows: [6] The coat symbolized of the earth, the upper garment symbolized heaven, while the bells and pomegranates represented thunder and lightning. The ephod typified the four elements, and the interwoven gold denoted the glory of God. The breastplate was in the center of the ephod, as the earth formed the center of the universe; the girdle symbolized the ocean, the stones on the shoulders the sun and moon, and the jewels in the breastplate the twelve signs of the zodiac, while the miter was a token of heaven.

The Jerusalem Talmud [7] and Midrash [8] described each garment as providing atonement for a specific sin: the coat for murder or for shatnez, the undergarment for unchastity, the miter for pride, the belt for theft or trickery, the breastplate for any perversion of the Law, the ephod for idolatry, and the robe for slander.

Various numbers play a significant role in Jewish texts or practice. Some such numbers were used as mnemonics to help remember concepts, while other numbers were considered to have intrinsic significance or allusive meaning. Numbers such as 7, 10, 12, and 40 were known for recurring in symbolic contexts.

Gematria is a form of cipher used to generate a numerical equivalent for a Hebrew word, which sometimes is invested with symbolic meaning. For example, the gematria of "chai" (the Hebrew word for life) is 18, and multiples of 18 are considered good luck and are often used in gift giving.

Gold was a highly regarded precious metal (as in other cultures), but was occasionally avoided due to its association with the sin of the golden calf. [9] Silver was associated with moral purity, as silver metal must be refined from its ore. [10] Brass symbolized hardness, strength, and firmness. [11] Brass was a substitute for gold, and iron for silver. [12]

Salt was offered with every sacrifice; [13] the preservative effect of salt symbolized the eternity of the covenant between God and Israel. [14] In the Talmud salt symbolizes the Torah, for just as "the world cannot exist without salt", so it can not endure without the Torah. [15]

The priestly breastplate, worn by the Kohen Gadol in the Temple in Jerusalem, had twelve stones representing the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The breastplate, or the stones on their own, are sometimes used as symbols.

In the Torah, the Israelites are commanded to dye one of the threads of their tzitzit (ritual fringes) with a blue-colored dye called tekhelet . [16] This dye was highly regarded in both Jewish and non-Jewish cultures of this time, and was worn by royalty and the upper-class. In the Torah, it also appears extensively in ritual contexts such as priestly garments and the curtains of the Tabernacle. Symbolically, in Jewish thought the color of tekhelet corresponds to the color of the heavens and the divine revelation. [17] The blue color of tekhelet was later used on the tallit, which typically has blue stripes on a white garment. From the 19th century at the latest, the combination of blue and white symbolized the Jewish people, [18] and this combination was chosen for the Flag of Israel.

Argaman (Tyrian purple) was another luxurious ancient dye, and was symbolic of royal power. [19]

Tola'at shani ("scarlet") was considered a striking and lively color, [20] and was used in priestly garments and other ritual items, [21] but could also symbolize sin. [22]

White (as in linen or wool garments) symbolized moral purity. [23]

Yellow has an association with an anti-Semitic forced identification mark (see Jewish hat and Yellow badge).

The Torah delineates three pilgrimage festivals: Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot. Each of these is tied to the agricultural cycle of the Israelites, and also has a theological symbolism.

Passover celebrated the rebirth of nature, and symbolized the origin of the Jewish people. The eating of bitter herbs symbolized the miseries of the Egyptian bondage. In the evenings four cups of wine were drunk, to symbolize the four world-kingdoms. [24] People eating during the Passover meal reclined, in the style of free rich aristocrats, to represent their liberation from slavery.

Jeremiah beheld an almond-tree as a token of the speedy fulfillment of the word of God. [25] Amos saw a basket of summer fruit as a symbol of the approaching end of Israel. [26]

Ahijah the Shilonite tore Jeroboam's mantle into twelve pieces, to typify the division of the kingdom of Israel, [27] and Zedekiah made horns of iron to encourage Ahab to engage in war with Ramoth-gilead. [28] King Joash, at the command of the prophet Elisha, shot arrows from the open window into the air, to symbolize the destruction of his enemies. [29]

Isaiah walked naked and barefoot to show how the Egyptians and Ethiopians would be treated when taken captive by the Assyrians, [30] while Jeremiah wore a yoke upon his neck to induce the nations to submit to the King of Assyria. [31] Ezekiel was commanded to inscribe the names of certain tribes upon separate pieces of wood, to show that God would reunite those tribes. [32]

Some common themes appear on many Jewish tombstones. Two hands with outspread fingers indicated that the dead man was descended from priestly stock ( Kohanim ) who blessed the people in this fashion, and a jug was carved on the tombstones of the Levites as an emblem of those who washed the priest's hands before he pronounced the blessing.

Some gravestones show a tree with branches either outspread or broken off, symbolizing the death of a young man or an old man respectively; or they have a cluster of grapes as an emblem of Israel.

The Star of David (Magen David) occurs frequently.

Sometimes figures symbolized the name of the deceased, as the figure of a lion for Loeb, a wolf for Benjamin, and a rose for the name Bluma/Blume.

Jewish symbols are prevalent on wimpels; Torah binders made from the cloth used to swaddle a child on his Brit Milah. Common themes and symbols are linked to positive wishes for the life of the child.

On Ashkenazi Torah binders, the inscriptions often follow the same pattern. After naming the son then the father and other relevant data, a standardised saying follows; the boy should grow to the chuppa (marriage canopy) and good deeds under the guidance of the Torah.

These sentences are usually illustrated with paintings or embroidery. Common symbols include plants or flowers, symbolising the tree of life (often equated with the Torah), a chuppa (to illustrate the wish for a marriage under the guidance of the Torah), a Torah scroll and crown, and animals. [33] These can reflect the zodiac constellation under which a child was born, or be a reference to their name and heritage. Deer might give an indication of the name Zvi (Hebrew), Hirsch (German) or Herschl (Yiddish), whereas a lion might symbolise the name Löw/Ariel. Lions are also associated with the Tribes of Israel, Judah and Dan. [34]

Zion is a Biblical term that refers to Jerusalem (and to some extent the whole Land of Israel), and is the source for the modern term Zionism. Mount Zion is a hill outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, but the term previously referred to the Temple Mount, as well as a hill in the City of David.

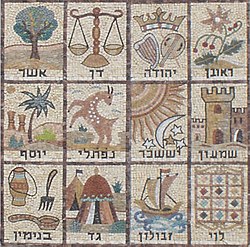

Various symbols have been attributed to the Twelve Tribes of Israel, most notably the Lion of Judah and the priestly breastplate of Levi.

Symbols attributed to the 12 tribes:

Historically Jews who carried arms often use the iconography of the Lion of Judah, the Star of David, and if they were Kohens, the symbol of two hands performing the priestly benediction.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)... symbols ... used by Jacob, just before his death, in his blessing to his sons in Genesis 49: Reuben is likened to water, Yehuda a lion, Zevulun a ship, Dan a snake and Naphtali a deer. Three other symbols match those used by Moses in his blessings to the tribes, just before his death, in Deuteronomy 33: Joseph is likened to a bull, Benjamin to two hills and Asher to oil or an olive tree. Of the remaining four tribal symbols, some can be found in other ancient Jewish sources. For example, the Midrash says Shimon's symbol was the gates to the city of Shechem (Midrash BaMidbar Rabbah 2:7).

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Symbol". The Jewish Encyclopedia . New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Symbol". The Jewish Encyclopedia . New York: Funk & Wagnalls.