Related Research Articles

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism, is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contemporary Western Ukraine during the 18th century, and spread rapidly throughout Eastern Europe. Today, most affiliates reside in Israel and the United States.

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on Mount Sinai and faithfully transmitted ever since.

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch, is an Orthodox Jewish Hasidic dynasty. Chabad is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, particularly for its outreach activities. It is one of the largest Hasidic groups and Jewish religious organizations in the world. Unlike most Haredi groups, which are self-segregating, Chabad operates mainly in the wider world and caters to secularized Jews.

A Rebbe or Admor is the spiritual leader in the Hasidic movement, and the personalities of its dynasties. The titles of Rebbe and Admor, which used to be a general honor title even before the beginning of the movement, became, over time, almost exclusively identified with its Tzaddikim.

Joel Teitelbaum was the founder and first Grand Rebbe of the Satmar dynasty.

Satmar is a Hasidic group founded in 1905 by Grand Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum, in the city of Szatmárnémeti, Hungary. The group is an offshoot of the Sighet Hasidic dynasty. Following World War II, it was re-established in New York.

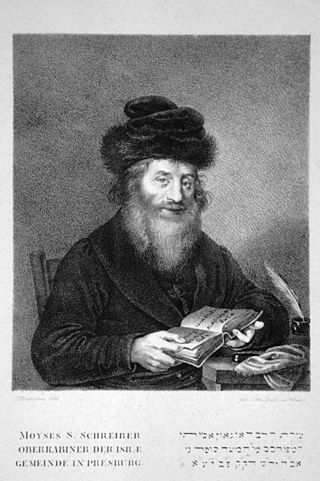

Moses Schreiber (1762–1839), known to his own community and Jewish posterity in the Hebrew translation as Moshe Sofer, also known by his main work Chatam Sofer, Chasam Sofer, or Hatam Sofer, was one of the leading Orthodox rabbis of European Jewry in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Schisms among the Jews are cultural as well as religious. They have happened as a product of historical accident, geography, and theology.

Munkatch Hasidism is a Hasidic sect within Haredi Judaism of mostly Hungarian Hasidic Jews. It was founded and led by Polish-born Grand Rebbe Shlomo Spira, who was the rabbi of the town of Strzyżów (1858–1882) and Munkacs (1882–1893). Members of the congregation are mainly referred to as Munkacs Hasidim, or Munkatcher Hasidim. It is named after the Hungarian town in which it was established, Munkatsh.

Shomer Emunim is a devout, insular Hasidic group based in Jerusalem. It was founded in the 20th century by Rabbi Arele (Aharon) Roth.

Moshe (Moses) Teitelbaum was a Hasidic rebbe and the world leader of the Satmar Hasidim.

Fateless or Fatelessness is a novel by Imre Kertész, winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize for literature, written between 1960 and 1973 and first published in 1975.

Yekusiel Yehuda III Teitelbaum, known by the Yiddish colloquial name Rav Zalman Leib, is one of two Grand Rebbes of Satmar, and the son of Grand Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum, the late Rebbe of the Satmar Hasidim. He is the son-in-law of the previous Bistritzer Rebbe of Brooklyn. He is currently one of the two Grand Rebbes of Satmar, with his faction being based in central Satmar congregation in Williamsburg, and the Dean of a Satmar yeshiva in Queens.

Oberlander Jews were the Jews who inhabited the northwestern regions of the historical Kingdom of Hungary, which are contemporary western Slovakia and Burgenland.

Der Yid is a New York-based Yiddish-language weekly newspaper, founded in 1953. The newspaper is published by Satmar Hasidim, but is widely read within the broader Yiddish-speaking Haredi community. It uses a Yiddish dialect common to Satmar Hasidim, as opposed to "YIVO Yiddish", which is standard in secular and academic circles.

Siget or Ujhel-Siget or Sighet Hasidism, or Sigter Hasidim, is a movement of Hungarian Haredi Jews who adhere to Hasidism, and who are referred to as Sigeter Hasidim.

Vien is an American Haredi Kehilla (community) originating in present-day Vienna. The name of their congregation is "Kehal Adas Yereim Vien".

Yochanan Sofer was the rebbe of the Erlau dynasty. He was born in Eger, Hungary, where his father and grandfather were also rebbes. After surviving the Holocaust, he founded a yeshiva, first in Hungary and then a few years later in Jerusalem.

The Schism in Hungarian Jewry was the institutional division of the Jewish community in the Kingdom of Hungary between 1869 and 1871, following a failed attempt to establish a national, united representative organization. The founding congress of the new body was held during an ongoing conflict between the traditionalist Orthodox party and its modernist Neolog rivals, which had been raging for decades.

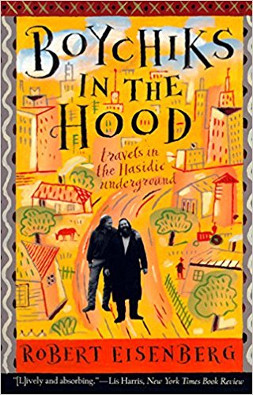

Boychiks in the Hood is a 1995 memoir by Robert Eisenberg that chronicles Eisenberg's travels around the world visiting different Hasidic communities. Einsenberg wrote the memoir as a way to explore communities where Yiddish was the first language spoken among all generations. It is widely recognized as a reputable source for information on Hasidic life.

References

- 1 2 Yeshayahu A. Jelinek, Paul R. Magocsi. The Carpathian Diaspora: The Jews of Subcarpathian Rus' and Mukachevo, 1848–1948. East European Monographs (2007). p. 5-6.

- 1 2 Menahem Keren-Kratz. Cultural Life in Maramaros County (Hungary, Romania, Czechoslovakia): Literature, Press and Jewish Thought, 1874–1944. Ph.D dissertation submitted to the Senate of Bar-Ilan University, 2008. OCLC 352874902. pp. 23-24.

- ↑ Michael K. Silber. The Emergence of Ultra-Orthodoxy: The Invention of Tradition . In: Jack Wertheimer, ed. The Uses of Tradition: Jewish Continuity since Emancipation (New York-Jerusalem: JTS distributed by Harvard U. Press, 1992). pp. 41-42.

- 1 2 Robert Perlman. Bridging Three Worlds: Hungarian-Jewish Americans, 1848–1914. University of Massachusetts Press (2009). p. 65.

- ↑ Imre Kertész. Fateless. Northwestern University Press, 1992. p. 101.

- ↑ Jechiel Bin-Nun. Jiddisch und die Deutschen Mundarten: Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung des Ostgalizischen Jiddisch. Walter de Gruyter (1973). p. 93.

- ↑ Steffen Krogh. How Satmarish is Satmar Yiddish? Jiddistik Heute. Düsseldorf Uni. Press, pp. 484-485.

- ↑ Kinga Froimovich. Who Were They? Characteristics of the Religious Trends of Hungarian Jewry on the Eve of their Extermination. Yad Vashem Studies, vol. 35, 2007. p. 153.