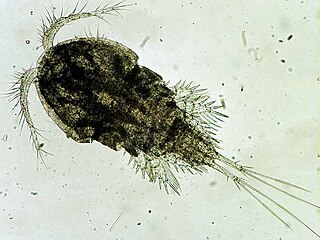

Copepods are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic, some are benthic, a number of species have parasitic phases, and some continental species may live in limnoterrestrial habitats and other wet terrestrial places, such as swamps, under leaf fall in wet forests, bogs, springs, ephemeral ponds, puddles, damp moss, or water-filled recesses of plants (phytotelmata) such as bromeliads and pitcher plants. Many live underground in marine and freshwater caves, sinkholes, or stream beds. Copepods are sometimes used as biodiversity indicators.

Tantulocarida is a highly specialised group of parasitic crustaceans that consists of about 33 species, treated as a class in superclass Multicrustacea. They are typically ectoparasites that infest copepods, isopods, tanaids, amphipods and ostracods.

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that are parasitic castrators. Their hosts are mostly decapod crustaceans, but include Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles. Their habitats range from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracica and Acrothoracica, they make up the subclass Cirripedia. Their body plan is uniquely reduced in an extreme adaptation to their parasitic lifestyle, and makes their relationship to other barnacles unrecognisable in the adult form. The name Rhizocephala derives from the Ancient Greek roots ῥίζα and κεφαλή, describing the adult female, which mostly consists of a network of thread-like extensions penetrating the body of the host.

The family Argulidae, whose members are commonly known as carp lice or fish lice, are parasitic crustaceans in the class Ichthyostraca. It is the only family in the monotypic subclass Branchiura and the order Arguloida, although a second family, Dipteropeltidae, has been proposed. Although they are thought to be primitive forms, they have no fossil record.

The Cyclopoida are an order of small crustaceans from the subclass Copepoda. Like many other copepods, members of Cyclopoida are small, planktonic animals living both in the sea and in freshwater habitats. They are capable of rapid movement. Their larval development is metamorphic, and the embryos are carried in paired or single sacs attached to first abdominal somite.

Thecostraca is a class of marine invertebrates containing over 2,200 described species. Many species have planktonic larvae which become sessile or parasitic as adults.

Macrocyclops albidus is a larvivorous copepod species.

Acartia hudsonica is a species of marine copepod belonging to the family Acartiidae. Acartia hudsonica is a coastal, cold water species that can be found along the northwest Atlantic coast.

Crustaceans may pass through a number of larval and immature stages between hatching from their eggs and reaching their adult form. Each of the stages is separated by a moult, in which the hard exoskeleton is shed to allow the animal to grow. The larvae of crustaceans often bear little resemblance to the adult, and there are still cases where it is not known what larvae will grow into what adults. This is especially true of crustaceans which live as benthic adults, more-so than where the larvae are planktonic, and thereby easily caught.

Pennellidae is a family of parasitic copepods. When anchored on a host, they have a portion of the body on the outside of the host, whereas the remaining anterior part of the parasite is hidden inside tissues of the host.

Crustaceans are a group of arthropods that are a part of the subphylum Crustacea, a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthropods including decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, opossum shrimps, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group can be treated as a subphylum under the clade Mandibulata. It is now well accepted that the hexapods emerged deep in the Crustacean group, with the completed group referred to as Pancrustacea. The three classes Cephalocarida, Branchiopoda and Remipedia are more closely related to the hexapods than they are to any of the other crustaceans.

The clade Multicrustacea constitutes the largest superclass of crustaceans, containing approximately four-fifths of all described crustacean species, including crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill, prawns, woodlice, barnacles, copepods, amphipods, mantis shrimp and others. The largest branch of multicrustacea is the class Malacostraca.

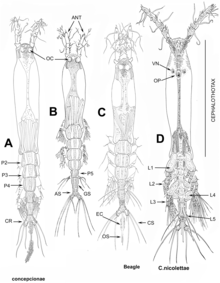

Protosarcotretes is a genus of marine copepods in the family Pennellidae. Its type-species is Protosarcotretes nishikawai. This genus exhibits the most plesiomorphic states in the first to fourth legs of pennellids, and is differentiated from two closely related pennellid genera Sarcotretes and Lernaeenicus by the morphology of the oral appendages.

Blastodinium is a diverse genus of dinoflagellates and important parasites of planktonic copepods. They exist in either a parasitic stage, a trophont stage, and a dinospore stage. Although morphologically and functionally diverse, as parasites they live exclusively in the intestinal tract of copeods.

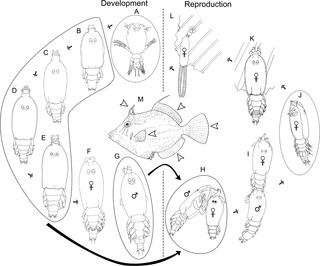

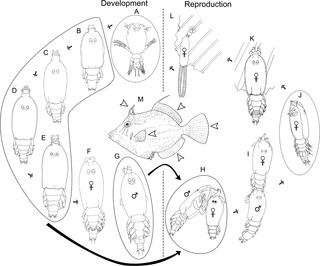

Peniculus minuticaudae is a species of parasitic pennellid copepod. It is known from the northeast Pacific Ocean. It was originally described in 1956, redescribed in 2012, and its complete life cycle has been elucidated on the cultured threadsail filefish, Stephanolepis cirrhifer in 2013.

Peniculus hokutoae is a species of parasitic pennellid copepod. It was described in 2018 from a single female. The type-host is the myctophid fish Symbolophorus evermanni and the type-locality is off Japan. The Japanese name of this species is hokuto-kozutsu-hijikimushi.

Longipedia is a genus of marine copepods of the family Longipediidae, order Canuelloida.

Mesocyclops longisetus is a species of freshwater copepod in the family Cyclopidae. Two subspecies are accepted, Mesocyclops longisetus curvatus Dussart, 1987, and Mesocyclops longisetus longisetus. It has a neotropical distribution.

Ergasilus curticrus is a freshwater parasitic copepod named in 2015. Described from the Orinoco river basin, it was found solely to be hosted by individuals of the Characiform fish species Bryconops giacopinii. Of those located in South America, it is one of only five species in its genus to be found outside of Brazil.