Related Research Articles

The Austrian school is a heterodox school of economic thought that advocates strict adherence to methodological individualism, the concept that social phenomena result primarily from the motivations and actions of individuals along with their self interest. Austrian-school theorists hold that economic theory should be exclusively derived from basic principles of human action.

The economic calculation problem (ECP) is a criticism of using central economic planning as a substitute for market-based allocation of the factors of production. It was first proposed by Ludwig von Mises in his 1920 article "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth" and later expanded upon by Friedrich Hayek.

Keynesian economics are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. It is influenced by a host of factors that sometimes behave erratically and impact production, employment, and inflation.

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the economy as a whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

A monopoly is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce a particular thing, a lack of viable substitute goods, and the possibility of a high monopoly price well above the seller's marginal cost that leads to a high monopoly profit. The verb monopolise or monopolize refers to the process by which a company gains the ability to raise prices or exclude competitors. In economics, a monopoly is a single seller. In law, a monopoly is a business entity that has significant market power, that is, the power to charge overly high prices, which is associated with unfair price raises. Although monopolies may be big businesses, size is not a characteristic of a monopoly. A small business may still have the power to raise prices in a small industry.

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption, and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good or service is determined through a hypothetical maximization of utility by income-constrained individuals and of profits by firms facing production costs and employing available information and factors of production. This approach has often been justified by appealing to rational choice theory.

In economics, specifically general equilibrium theory, a perfect market, also known as an atomistic market, is defined by several idealizing conditions, collectively called perfect competition, or atomistic competition. In theoretical models where conditions of perfect competition hold, it has been demonstrated that a market will reach an equilibrium in which the quantity supplied for every product or service, including labor, equals the quantity demanded at the current price. This equilibrium would be a Pareto optimum.

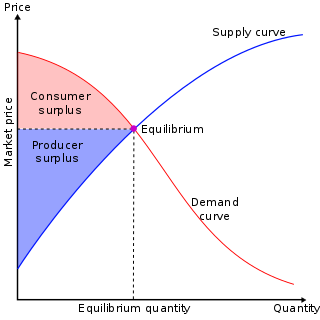

In microeconomics, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It postulates that, holding all else equal, the unit price for a particular good or other traded item in a perfectly competitive market, will vary until it settles at the market-clearing price, where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied such that an economic equilibrium is achieved for price and quantity transacted. The concept of supply and demand forms the theoretical basis of modern economics.

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus, is either of two related quantities:

Post-Keynesian economics is a school of economic thought with its origins in The General Theory of John Maynard Keynes, with subsequent development influenced to a large degree by Michał Kalecki, Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor, Sidney Weintraub, Paul Davidson, Piero Sraffa and Jan Kregel. Historian Robert Skidelsky argues that the post-Keynesian school has remained closest to the spirit of Keynes' original work. It is a heterodox approach to economics based on a non-equilibrium approach.

This aims to be a complete article list of economics topics:

Business cycles are intervals of general expansion followed by recession in economic performance. The changes in economic activity that characterize business cycles have important implications for the welfare of the general population, government institutions, and private sector firms.

Allocative efficiency is a state of the economy in which production is aligned with the preferences of consumers and producers; in particular, the set of outputs is chosen so as to maximize the social welfare of society. This is achieved if every produced good or service has a marginal benefit equal to the marginal cost of production.

In economics, market power refers to the ability of a firm to influence the price at which it sells a product or service by manipulating either the supply or demand of the product or service to increase economic profit. In other words, market power occurs if a firm does not face a perfectly elastic demand curve and can set its price (P) above marginal cost (MC) without losing revenue. This indicates that the magnitude of market power is associated with the gap between P and MC at a firm's profit maximising level of output. The size of the gap, which encapsulates the firm's level of market dominance, is determined by the residual demand curve's form. A steeper reverse demand indicates higher earnings and more dominance in the market. Such propensities contradict perfectly competitive markets, where market participants have no market power, P = MC and firms earn zero economic profit. Market participants in perfectly competitive markets are consequently referred to as 'price takers', whereas market participants that exhibit market power are referred to as 'price makers' or 'price setters'.

The history of economic thought is the study of the philosophies of the different thinkers and theories in the subjects that later became political economy and economics, from the ancient world to the present day.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to economics:

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

Throughout modern history, a variety of perspectives on capitalism have evolved based on different schools of thought.

In microeconomics, a monopoly price is set by a monopoly. A monopoly occurs when a firm lacks any viable competition and is the sole producer of the industry's product. Because a monopoly faces no competition, it has absolute market power and can set a price above the firm's marginal cost.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions containing terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.

References

- ↑ Boudreaux, Donald J. "Information and Prices". The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Library of Economics and Liberty (econlib.org). Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ Hayek, Friedrich (1945). "The use of knowledge in society". American Economic Review. XXXV (4): 519–530. JSTOR 1809376.

- ↑ "Cartels". Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. 2013-01-09. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ Schroeder, Mark (2016), "Value Theory", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2020-11-09

- ↑ Gopinath, Gita (April 14, 2020). "The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression". International Monetary Fund .

- ↑ Dequech, David (2012). "Post Keynesianism, Heterodoxy and Mainstream Economics". Review of Political Economy. 24 (2): 353–368. doi : 10.1080/09538259.2012.664364. ISSN 0953-8259.

- ↑ Lavoie, Marc (2006), "Post-Keynesian Heterodoxy", Introduction to Post-Keynesian Economics, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 1–24, doi : 10.1057/9780230626300_1, ISBN 978-1-349-28337-8

- ↑ Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler, Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder , Routledge, 2009, p. 228.