The "Ainulindalë" is the creation account in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, published posthumously as the first part of The Silmarillion in 1977. The "Ainulindalë" sets out a central part of the cosmology of Tolkien's legendarium, telling how the Ainur, a class of angelic beings, perform a great music prefiguring the creation of the material universe, Eä, including Middle-Earth. The creator Eru Ilúvatar introduces the theme of the sentient races of Elves and Men, not anticipated by the Ainur, and gives physical being to the prefigured universe. Some of the Ainur decide to enter the physical world to prepare for their arrival, becoming the Valar and Maiar.

Valinor or the Blessed Realm is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he used the name Aman mainly to mean Valinor. It includes Eldamar, the land of the Elves, who as immortals are permitted to live in Valinor.

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Noldor are a kindred of Elves who migrate west to the blessed realm of Valinor from the continent of Middle-earth, splitting from other groups of Elves as they went. They then settle in the coastal region of Eldamar. The Dark Lord Morgoth murders their first leader, Finwë. The majority of the Noldor, led by Finwë's eldest son Fëanor, then return to Beleriand in the northwest of Middle-earth. This makes them the only group to return and then play a major role in Middle-earth's history; much of The Silmarillion is about their actions. They are the second clan of the Elves in both order and size, the other clans being the Vanyar and the Teleri.

Morgoth's Ring (1993) is the tenth volume of Christopher Tolkien's 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth in which he analyses the unpublished manuscripts of his father J. R. R. Tolkien.

The Lost Road and Other Writings – Language and Legend before 'The Lord of the Rings' is the fifth volume of The History of Middle-earth, a series of compilations of drafts and essays written by J. R. R. Tolkien in around 1936–1937. It was edited and published posthumously in 1987 by Christopher Tolkien.

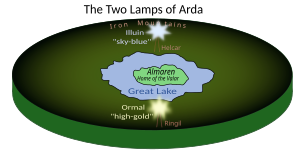

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the history of Arda, also called the history of Middle-earth, began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional universe. Time from that point was measured using Valian Years, though the subsequent history of Arda was divided into three time periods using different years, known as the Years of the Lamps, the Years of the Trees, and the Years of the Sun. A separate, overlapping chronology divides the history into 'Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar'. The first such Age began with the Awakening of the Elves during the Years of the Trees and continued for the first six centuries of the Years of the Sun. All the subsequent Ages took place during the Years of the Sun. Most Middle-earth stories take place in the first three Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the Two Trees of Valinor are Telperion and Laurelin, the Silver Tree and the Gold Tree, which bring light to Valinor, a paradisiacal realm where angelic beings live. The Two Trees are of enormous stature, and exude dew that is a pure and magical light in liquid form. The craftsman Elf Fëanor makes the unrivalled jewels, the Silmarils, with their light. The Two Trees are destroyed by the evil beings Ungoliant and Melkor, but their last flower and fruit are made into the Moon and the Sun. Melkor, now known as Morgoth, steals the Silmarils, provoking the disastrous War of the Jewels. Descendants of Telperion survive, growing in Númenor and, after its destruction, in Gondor; in both cases the trees are symbolic of those kingdoms. For many years while Gondor has no King, the White Tree of Gondor stands dead in the citadel of Minas Tirith. When Aragorn restores the line of Kings to Gondor, he finds a sapling descended from Telperion and plants it in his citadel.

Tolkien's legendarium is the body of J. R. R. Tolkien's mythopoeic writing, unpublished in his lifetime, that forms the background to his The Lord of the Rings, and which his son Christopher summarized in his compilation of The Silmarillion and documented in his 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth. The legendarium's origins reach back to 1914, when Tolkien began writing poems and story sketches, drawing maps, and inventing languages and names as a private project to create a unique English mythology. The earliest story drafts are from 1916; he revised and rewrote these for most of his adult life.

The cosmology of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium combines aspects of Christian theology and metaphysics with pre-modern cosmological concepts in the flat Earth paradigm, along with the modern spherical Earth view of the Solar System.

The Ainur (singular: Ainu) are the immortal spirits existing before the Creation in J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional universe. These were the first beings made of the thought of Eru Ilúvatar. They were able to sing such beautiful music that the world was created from it.

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civilization of Men. However, after centuries of prosperity many of the inhabitants ceased to worship the One God, Eru Ilúvatar, and rebelled against the Valar, resulting in the destruction of the island and the death of most of its people. Tolkien intended Númenor to allude to the legendary Atlantis. Commentators have noted that the destruction of Númenor echoes the Biblical stories of the fall of man and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and John Milton's Paradise Lost.

The Maiar are a fictional class of beings from J. R. R. Tolkien's high fantasy legendarium. Supernatural and angelic, they are "lesser Ainur" who entered the cosmos of Eä in the beginning of time. The name Maiar is in the Quenya tongue from the Elvish root maya- "excellent, admirable".

Middle-earth is the setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the human-inhabited world, that is, the central continent of the Earth, in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

Morgoth Bauglir is a character, one of the godlike Valar, from Tolkien's legendarium. He is the primary antagonist of The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin.

The Silmarils are three fictional brilliant jewels in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, made by the Elf Fëanor, capturing the unmarred light of the Two Trees of Valinor. The Silmarils play a central role in Tolkien's book The Silmarillion, which tells of the creation of Eä and the beginning of Elves, Dwarves and Men.

The Valar are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. They are "angelic powers" or "gods" subordinate to the one God. The Ainulindalë describes how some of the Ainur choose to enter the World (Arda) to complete its material development after its form is determined by the Music of the Ainur. The mightiest of these are called the Valar, or "the Powers of the World", and the others are known as the Maiar.

The Silmarillion is a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by Guy Gavriel Kay, who became a fantasy author. It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher, Stanley Unwin, requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the writings that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

Trees play multiple roles in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth, some such as Old Man Willow indeed serving as characters in the plot. Both for Tolkien personally, and in his Middle-earth writings, caring about trees really mattered. Indeed, the Tolkien scholar Matthew Dickerson wrote "It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of trees in the writings of J. R. R. Tolkien."

J. R. R. Tolkien built a process of decline and fall in Middle-earth into both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien was attracted to medieval literature, and made use of it in his writings, both in his poetry, which contained numerous pastiches of medieval verse, and in his Middle-earth novels where he embodied a wide range of medieval concepts.