Apollo 8 was the first crewed spacecraft to leave low Earth orbit and the first human spaceflight to reach the Moon. The crew orbited the Moon ten times without landing, and then departed safely back to Earth. These three astronauts—Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders—were the first humans to witness and photograph the far side of the Moon and an Earthrise.

Edward Higgins White II was an American aeronautical engineer, United States Air Force officer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut. He was a member of the crews of Gemini 4 and Apollo 1.

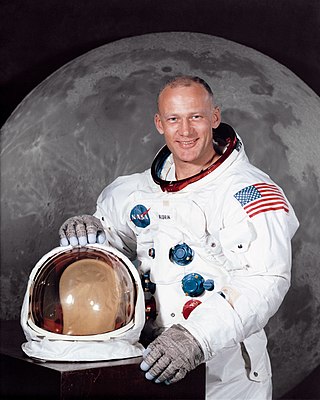

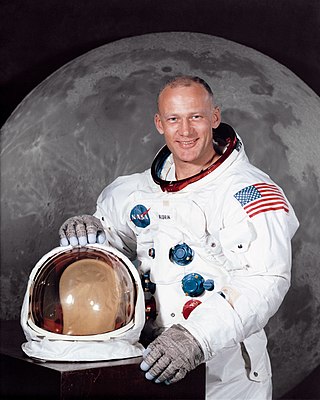

Buzz Aldrin is an American former astronaut, engineer and fighter pilot. He made three spacewalks as pilot of the 1966 Gemini 12 mission, and was the Lunar Module Eagle pilot on the 1969 Apollo 11 mission. He was the second person to walk on the Moon after mission commander Neil Armstrong.

Frank Frederick Borman II was an American United States Air Force (USAF) colonel, aeronautical engineer, NASA astronaut, test pilot, and businessman. He was the commander of Apollo 8, the first mission to fly around the Moon, and together with crewmates Jim Lovell and William Anders, became the first of 24 humans to do so, for which he was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor.

Michael Collins was an American astronaut who flew the Apollo 11 command module Columbia around the Moon in 1969 while his crewmates, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, made the first crewed landing on the surface. He was also a test pilot and major general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

David Randolph Scott is an American retired test pilot and NASA astronaut who was the seventh person to walk on the Moon. Selected as part of the third group of astronauts in 1963, Scott flew to space three times and commanded Apollo 15, the fourth lunar landing; he is one of four surviving Moon walkers and the only living commander of a spacecraft that landed on the Moon.

Charles Moss Duke Jr. is an American former astronaut, United States Air Force (USAF) officer and test pilot. As Lunar Module pilot of Apollo 16 in 1972, he became the 10th and youngest person to walk on the Moon, at age 36 years and 201 days.

Stuart Allen Roosa was an American aeronautical engineer, smokejumper, United States Air Force pilot, test pilot, and NASA astronaut, who was the Command Module Pilot for the Apollo 14 mission. The mission lasted from January 31 to February 9, 1971, and was the third mission to land astronauts on the Moon. While Shepard and Mitchell spent two days on the lunar surface, Roosa conducted experiments from orbit in the Command Module Kitty Hawk. He was one of 24 men to travel to the Moon, which he orbited 34 times.

James Arthur Lovell Jr. is an American retired astronaut, naval aviator, test pilot and mechanical engineer. In 1968, as command module pilot of Apollo 8, he became, with Frank Borman and William Anders, one of the first three astronauts to fly to and orbit the Moon. He then commanded the Apollo 13 lunar mission in 1970 which, after a critical failure en route, looped round the Moon and returned safely to Earth.

Fred Wallace Haise Jr. is an American former NASA astronaut, engineer, fighter pilot with the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Air Force, and a test pilot. He is one of 24 people to have flown to the Moon, having flown as Lunar Module pilot on Apollo 13. He was slated to become the 6th person to walk on the Moon, but the Apollo 13 landing mission was aborted en route.

Joe Henry Engle is an American pilot, aeronautical engineer and former NASA astronaut. He was the commander of two Space Shuttle missions including STS-2 in 1981, the program's second orbital flight. He also flew two flights in the Shuttle program's 1977 Approach and Landing Tests. Engle is one of twelve pilots who flew the North American X-15, an experimental spaceplane jointly operated by the Air Force and NASA, and the last surviving test pilot of the aircraft. After Richard H. Truly died In 2024, Engle is now the last surviving crew member of STS-2.

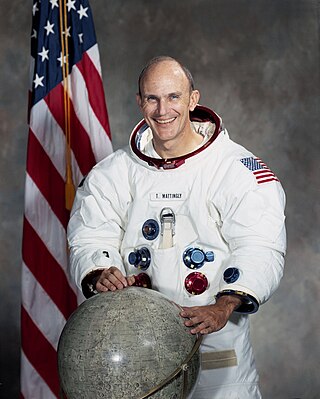

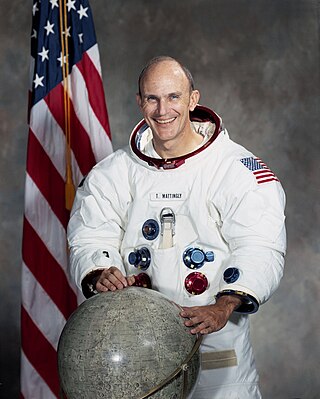

Thomas Kenneth Mattingly II was an American aviator, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, rear admiral in the United States Navy, and astronaut who flew on Apollo 16 and Space Shuttle STS-4 and STS-51-C missions.

James Alton McDivitt Jr. was an American test pilot, United States Air Force (USAF) pilot, aeronautical engineer, and NASA astronaut in the Gemini and Apollo programs. He joined the USAF in 1951 and flew 145 combat missions in the Korean War. In 1959, after graduating first in his class with a Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the University of Michigan through the U.S. Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) program, he qualified as a test pilot at the Air Force Experimental Flight Test Pilot School and Aerospace Research Pilot School, and joined the Manned Spacecraft Operations Branch. By September 1962, McDivitt had logged over 2,500 flight hours, of which more than 2,000 hours were in jet aircraft. This included flying as a chase pilot for Robert M. White's North American X-15 flight on July 17, 1962, in which White reached an altitude of 59.5 miles (95.8 km) and became the first X-15 pilot to be awarded Astronaut Wings.

Thomas Patten Stafford was an American Air Force officer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut, and one of 24 astronauts who flew to the Moon. He also served as Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1969 to 1971.

The United States Astronaut Badge is a badge of the United States, awarded to military and civilian personnel who have completed training and performed a successful spaceflight. A variation of the astronaut badge is also issued to civilians who are employed with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as specialists on spaceflight missions. It is the least-awarded qualification badge of the United States military.

Project Gemini was the second United States human spaceflight program to fly. Conducted after the first American manned space program, Project Mercury, while the Apollo program was still in early development, Gemini was conceived in 1961 and concluded in 1966. The Gemini spacecraft carried a two-astronaut crew. Ten Gemini crews and 16 individual astronauts flew low Earth orbit (LEO) missions during 1965 and 1966.

Charles Arthur "Charlie" Bassett II, , was an American electrical engineer and United States Air Force test pilot. He went to Ohio State University for two years and later graduated from Texas Tech University with a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering. He joined the Air Force as a pilot and graduated from both the Air Force's Experimental Test Pilot School and the Aerospace Research Pilot School. Bassett was married and had two children.

NASA Astronaut Group 2, also known as the Next Nine and the New Nine, was the second group of astronauts selected by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Their selection was announced on September 17, 1962. The group augmented the Mercury Seven. President John F. Kennedy had announced Project Apollo, on May 25, 1961, with the ambitious goal of putting a man on the Moon by the end of the decade, and more astronauts were required to fly the two-man Gemini spacecraft and three-man Apollo spacecraft then under development. The Mercury Seven had been selected to accomplish the simpler task of orbital flight, but the new challenges of space rendezvous and lunar landing led to the selection of candidates with advanced engineering degrees as well as test pilot experience.

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1968, the crew of Apollo 8, the first humans to travel to the Moon, read from the Book of Genesis during a television broadcast. During their ninth orbit of the Moon astronauts Bill Anders, Jim Lovell, and Frank Borman recited verses 1 through 10 of the Genesis creation narrative from the King James Bible. Anders read verses 1–4, Lovell verses 5–8, and Borman read verses 9 and 10.

Earthrise is a photograph of Earth and part of the Moon's surface that was taken from lunar orbit by astronaut William Anders on December 24, 1968, during the Apollo 8 mission. Nature photographer Galen Rowell described it as "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken".