Biography

Atanacković was from a very respectable bourgeois family, where Serbian tradition was honoured scrupulously. He started school at an early age in his village. He attended high school at the Gymnasium of Karlovci before pursuing higher studies at the universities of the Hungarian and Austrian capitals.

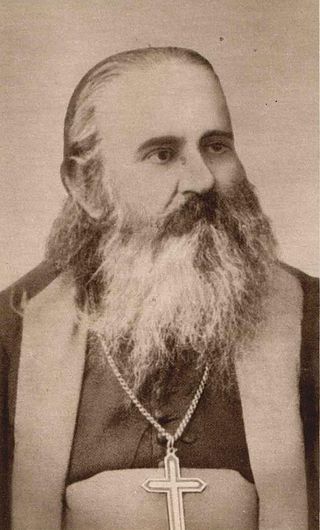

Atanacković resumed his law studies, which he had begun at universities in Budapest and in Vienna, where he frequented the circle of Serbian romanticists, followers of Vuk Karadžić; he was friends with Đuro Daničić and poet Branko Radičević. As a result of his participation in the Serbian Movement of 1848 and at the May Assembly in Sremski Karlovci, he was forced to flee to Vienna and later to Paris, from where he travelled throughout France, Switzerland, Germany, England and Italy. He came to Novi Sad in 1851 and worked as a secretary of the Orthodox bishop, Platon Atanacković. He continued his literary work, which he had started during his studies in Vienna, and in 1852 he returned to Baja, where he opened a law office. [1] He died in 1858 of tuberculosis. He was 32.

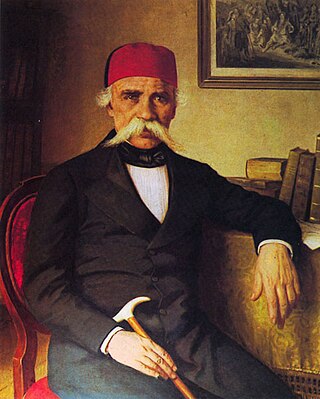

He posed for a portrait when he was around fourteen, probably at the end of the first years of high school, a child from a respectable merchant family in Baja; the portraitist was either of Austrian or Hungarian origin, but his identity still remains unknown. Atanacković was painted with a book in his right hand, in a manner customary at the time for portraits of older children who attended school or came from educated families. He was predestined to study law. Neither a child, nor an adult, with a serious expression on his face, but with the size of a child, clothed according to the style of the upper classes, bourgeoisie or nobility (Artist Jovan Popović painted the portrait of distinguished and ageing Sava Tekelija wearing such clothes), the future lawyer was depicted in a typical, slightly stiff pose, characteristic of a Biedermeier painting. His body and his arms are somewhat disproportionate to his head, but his face is painted carefully, with extraordinary warmth and directness. The details on his clothes - the decorative stripes, the buttons, the folds of his coat, the bow on his shirt - are accentuated in their simplicity to emphasize the importance of the depicted person.

"Dva idola (1851)" made him famous. He suddenly found himself in demand as a novelist of the first order. Today Atanacković is not looked upon that way by current critics, but then we're living in a different time. His stories are in part autobiographical or based on lives of people he knew: to invent for him was to remember. His stories usually had a foundation in fact and, in addition, his choice of realistic detail within loosely spun plots gave his work an air of verisimilitude. Even so, he achieved his effects by his "easy, plain, and familiar language of the common folk," taught him by Karadzić and Daničić when he was studying in Vienna for his law degree.

Bogoboj Atanacković brought to the Serbian novel a sense of tragic pessimism expressed with stoic restraint. Nothing in his external circumstances of his life explains this point of view, except for the current events which he witnessed a wrote about both in the guise of his novels, sentimental patriotic stories, and autobiography. He was brought up in Baja, Hungary, and his closeness to simple rural life probably helped him to penetrate to the central motives of existence. After travelling through Western Europe for two years, Atanackovic settled in Novi Sad, preferring to try his hand at writing novels than practicing law. In subsequent novels his world became increasingly one of grim tereenism—crass casualty—equally devoid of divine intent and of materialistic logic. Chance, accident, coincidence determine the outcome of human effort in his case, and the case for most of us.

As a novelist and short story writer Bogoboj Atanacković came to hold definite theories of the purposes and values of fiction, which he set forth in the essays collected after his death in the "Collection of the Works by Bogoboj Atanacković."