Little Solsbury Hill is a small flat-topped hill and the site of an Iron Age hill fort, above the village of Batheaston in Somerset, England. The hill rises to 625 feet (191 m) above the River Avon, which is just over 1 mile (2 km) to the south, and gives views of the city of Bath and the surrounding area. It is within the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Brean Down is a promontory off the coast of Somerset, England, standing 318 feet (97 m) high and extending 1+1⁄2 miles into the Bristol Channel at the eastern end of Bridgwater Bay between Weston-super-Mare and Burnham-on-Sea.

Small Down Knoll, or Small Down Camp, is a Bronze Age hill fort near Evercreech in Somerset, England. The hill is on the southern edge of the Mendip Hills, and rises to 222 m (728 ft).

Dunkery Beacon at the summit of Dunkery Hill is the highest point on Exmoor and in Somerset, England. It is also the highest point in southern England outside of Dartmoor.

Cadbury Camp is an Iron Age hill fort in Somerset, England, near the village of Tickenham. It is a scheduled monument. Although primarily known as a fort during the Iron Age it is likely, from artefacts, including a bronze spear or axe head, discovered at the site, that it was first used in the Bronze Age and still occupied through the Roman era into the sub-Roman period when the area became part of a Celtic kingdom. The name may mean "Fort of Cador" - Cado(r) being possibly the regional king or warlord controlling Somerset, Bristol, and South Gloucestershire, in the middle to late 5th century. Cador has been associated with Arthurian England, though the only evidence for this is the reference in the Life of St. Carantoc to Arthur and Cador ruling from Dindraithou and having the power over western Somerset to grant Carantoc's plea to build a church at Carhampton. Geoffrey of Monmouth invented the title 'Duke of Cornwall' for Cador in his misleading History of the Kings of Britain.

Worlebury Hill is the name given to an upland area lying between the flatlands of Weston-super-Mare and the Kewstoke area of North Somerset, England. Worlebury Hill's rises from sea level to its highest point of 109 metres (358 ft), and the western end of the hill forms a peninsula, jutting out into the Bristol Channel, between Weston Bay and Sand Bay. A toll road follows the coast around the hill from Sand Bay in the north to the now derelict Birnbeck Pier in the west, although tolls are not currently collected on the road. Worlebury Golf Club is situated on the Hill and the area is known for being one of the wealthiest areas in the county of Somerset.

Midsummer Hill is situated in the range of Malvern Hills that runs approximately 13 kilometres (8 mi) north-south along the Herefordshire-Worcestershire border. It lies to the south of Herefordshire Beacon with views to Eastnor Castle. It has an elevation of 284 metres (932 ft). To the north is Swinyard Hill. It is the site of an Iron Age hill fort which spans Midsummer Hill and Hollybush Hill. The hillfort is protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument and is owned by Natural England. It can be accessed via a footpath which leads south from the car park at British Camp on the A449 or a footpath which heads north from the car park in Hollybush on the A438.

Worlebury Camp is the site of an Iron Age hillfort on Worlebury Hill, north of Weston-super-Mare in Somerset, England. The fort was well defended with numerous walls, embankments and ditches around the site. Several large triangular platforms have been uncovered around the sides of the fort, lower down on the hillside. Nearly one hundred storage pits of various sizes were cut into the bedrock, and many of these contained human remains, coins, and other artefacts. During the 19th and 20th centuries the fort suffered damage and was threatened with complete destruction on multiple occasions. Now, the site is a designated Scheduled monument. It falls within the Weston Woods Local Nature Reserve which was declared to Natural England by the North Somerset Council in 2005.

Brent Knoll Camp is an Iron Age hillfort at Brent Knoll, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from Burnham-on-Sea, Somerset, England. It has been designated as a Scheduled Monument, and is now in the care of the National Trust.

Dinedor Camp is an Iron Age hillfort, about 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) west of the village of Dinedor and about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south of Hereford in England. It is a scheduled monument.

There are over 670 scheduled monuments in the ceremonial county of Somerset in South West England. The county consists of a non-metropolitan county, administered by Somerset County Council, which is divided into five districts, and two unitary authorities. The districts of Somerset are West Somerset, South Somerset, Taunton Deane, Mendip and Sedgemoor. The two administratively independent unitary authorities, which were established on 1 April 1996 following the breakup of the county of Avon, are North Somerset and Bath and North East Somerset. These unitary authorities include areas that were once part of Somerset before the creation of Avon in 1974.

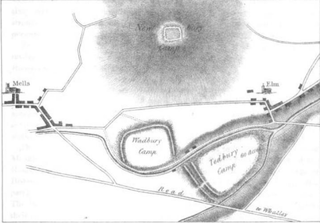

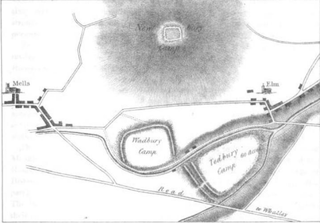

Wadbury Camp is a promontory fort in Somerset, England that protected the mining district of the Mendip Hills in pre-Roman times. It seems to have been an outwork of the larger Tedbury Camp.

Dungeon Hill is an Iron Age hillfort, about 1+1⁄4 miles north of the village of Buckland Newton in Dorset, England. It is a scheduled monument.

Banbury Hillfort, or Banbury Hill Camp, is an Iron Age hillfort, about 1.25 miles (2.0 km) south of Sturminster Newton and 1 mile (1.6 km) north-west of the village of Okeford Fitzpaine in Dorset, England.