Unless otherwise noted, statements in this article refer to Standard Finnish, which is based on the dialect spoken in the former Häme Province in central south Finland. Standard Finnish is used by professional speakers, such as reporters and news presenters on television.

The Northeast Caucasian languages, also called East Caucasian, Nakh-Daghestani or Vainakh-Daghestani, or sometimes Caspian languages, is a family of languages spoken in the Russian republics of Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia and in Northern Azerbaijan as well as in Georgia and diaspora populations in Western Europe and the Middle East. According to Glottolog, there are currently 36 Nakh-Dagestanian languages.

Chechen is a Northeast Caucasian language spoken by approximately 1.8 million people, mostly in the Chechen Republic and by members of the Chechen diaspora throughout Russia and the rest of Europe, Jordan, Austria, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Central Asia and Georgia.

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Oromo, historically also called Galla, which is regarded by the Oromo as pejorative, is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.

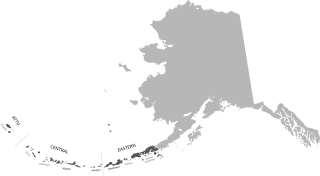

Aleut or Unangam Tunuu is the language spoken by the Aleut living in the Aleutian Islands, Pribilof Islands, Commander Islands, and the Alaska Peninsula. Aleut is the sole language in the Aleut branch of the Eskimo–Aleut language family. The Aleut language consists of three dialects, including Unalaska, Atka/Atkan, and Attu/Attuan.

In phonetics and phonology, gemination, or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from stress. Gemination is represented in many writing systems by a doubled letter and is often perceived as a doubling of the consonant. Some phonological theories use 'doubling' as a synonym for gemination, while others describe two distinct phenomena.

Iñupiaq or Inupiaq, also known as Iñupiat, Inupiat, Iñupiatun or Alaskan Inuit, is an Inuit language, or perhaps group of languages, spoken by the Iñupiat people in northern and northwestern Alaska, as well as a small adjacent part of the Northwest Territories of Canada. The Iñupiat language is a member of the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language family, and is closely related and, to varying degrees, mutually intelligible with other Inuit languages of Canada and Greenland. There are roughly 2,000 speakers. Iñupiaq is considered to be a threatened language, with most speakers at or above the age of 40. Iñupiaq is an official language of the State of Alaska, along with several other indigenous languages.

The Muscogee language, previously referred to by its exonym, Creek, is a Muskogean language spoken by Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole people, primarily in the US states of Oklahoma and Florida. Along with Mikasuki, when it is spoken by the Seminole, it is known as Seminole.

West Germanic gemination was a sound change that took place in all West Germanic languages around the 3rd or 4th century AD. It affected consonants directly followed by, which were generally lengthened or geminated in that position. Because of Sievers' law, only consonants immediately after a short vowel were affected by the process.

Tübatulabal is an Uto-Aztecan language, traditionally spoken in Kern County, California, United States. It is the traditional language of the Tübatulabal, who have switched to English. The language originally had three main dialects: Bakalanchi, Pakanapul and Palegawan.

The Bezhta language, also known as Kapucha, belongs to the Tsezic group of the North Caucasian language family. It is spoken by about 6,200 people in southern Dagestan, Russia.

Tsez, also known as Dido, is a Northeast Caucasian language with about 15,000 speakers spoken by the Tsez, a Muslim people in the mountainous Tsunta District of southwestern Dagestan in Russia. The name is said to derive from the Tsez word for 'eagle', but this is most likely a folk etymology. The name Dido is derived from the Georgian word დიდი, meaning 'big'.

Hunzib is a Northeast Caucasian language spoken by the Hunzib people in southern Dagestan, near the Russian border with Georgia.

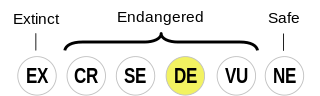

The Awngi language, in older publications also called Awiya, is a endangered indigenous Central Cushitic language spoken by the Awi people, traditionally living in Central Gojjam in northwestern Ethiopia.

The Gujarati language is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat. Much of its phonology is derived from Sanskrit.

Ale is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in southern Ethiopia in the administratively part of the "South Ethiopia Regional State" (SERS). It is part of the Dullay dialect cluster.

Pech or Pesh is a Chibchan language spoken in Honduras. It was formerly known as Paya, and continues to be referred to in this manner by several sources, though there are negative connotations associated with this term. It has also been referred to as Seco. There are 300 speakers according to Yasugi (2007). It is spoken near the north-central coast of Honduras, in the Dulce Nombre de Culmí municipality of Olancho Department.

This article describes the grammar of the Old Irish language. The grammar of the language has been described with exhaustive detail by various authors, including Thurneysen, Binchy and Bergin, McCone, O'Connell, Stifter, among many others.

The Inkhoqwarilanguage is a Northeast Caucasian language of the Tsezic group, closely related to, and typically considered a dialect of, Khwarshi. It separated from Khwarshi in the 9th century.