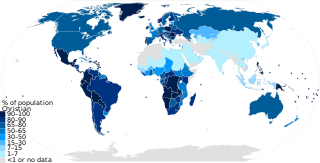

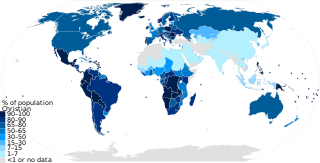

Christendom refers to Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.

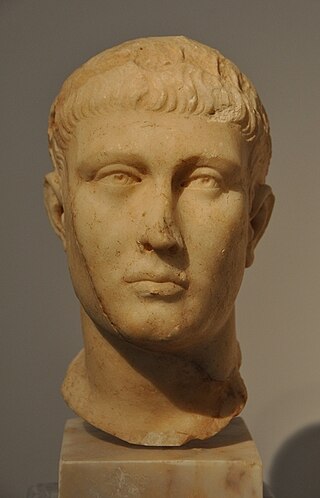

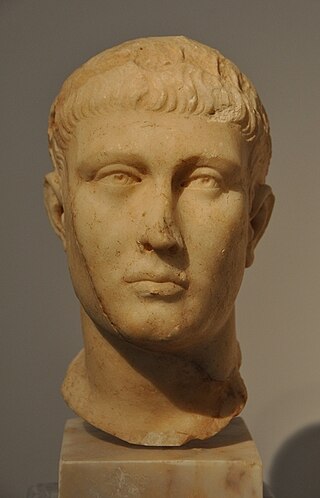

Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a pivotal role in elevating the status of Christianity in Rome, decriminalizing Christian practice and ceasing Christian persecution in a period referred to as the Constantinian shift. This initiated the cessation of the established ancient Roman religion. Constantine is also the originator of the religiopolitical ideology known as Constantinianism, which epitomizes the unity of church and state, as opposed to separation of church and state. He founded the city of Constantinople and made it the capital of the Empire, which remained so for over a millennium.

The history of Christianity follows the Christian religion as it developed from its earliest beliefs and practices in the first-century, spread geographically in the Roman Empire and beyond, and became a global religion in the twenty-first century.

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (yazata) Mithra, the Roman Mithras was linked to a new and distinctive imagery, and the level of continuity between Persian and Greco-Roman practice remains debatable. The mysteries were popular among the Imperial Roman army from the 1st to the 4th century CE.

Theodosius I, also called Theodosius the Great, was a Roman emperor from 379 to 395. He won two civil wars, and was instrumental in establishing the Nicene Creed as the orthodox doctrine for Nicene Christianity. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire before its administration was permanently split between the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. He successfully ended the Gothic War (376–382) with terms advantageous to the empire, with the Goths remaining in Roman territory but as subject allies.

The Edict of Milan was the February, AD 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire, which occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica, when Nicene Christianity received normative status.

The Chi Rho is one of the earliest forms of the Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ in such a way that the vertical stroke of the rho intersects the center of the chi.

Christianization is a term for the specific type of change that occurs when someone or something has been or is being converted to Christianity. Christianization has, for the most part, spread through missions by individual conversions and has, in most instances, been the result of violence by governments, military and Christians. Christianization is also the term used to designate the conversion of previously non-Christian practices, spaces and places to Christian uses and names. In a third manner, the term has been used to describe the changes that naturally emerge in a nation when sufficient numbers of individuals convert, or when secular leaders require those changes. Christianization of a nation is an ongoing process.

Late antiquity is sometimes defined as spanning from the end of classical antiquity to the local start of the Middle Ages, from around the late 3rd century up to the 7th or 8th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin depending on location. The popularisation of this periodization in English has generally been credited to historian Peter Brown, who proposed a period between 150–750 AD. The Oxford Centre for Late Antiquity defines it as "the period between approximately 250 and 750 AD". Precise boundaries for the period are a continuing matter of debate. In the West, its end was earlier, with the start of the Early Middle Ages typically placed in the 6th century, or even earlier on the edges of the Western Roman Empire.

During the reign of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great (306–337 AD), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to. There is no consensus among scholars as to whether he adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or, as claimed by Eusebius of Caesarea, encouraged her to convert to the faith he had adopted.

Christian apologetics is a branch of Christian theology that defends Christianity.

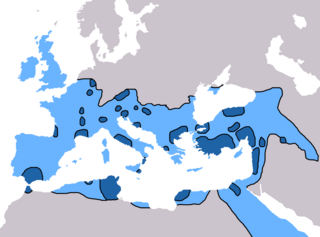

The growth of Christianity from its obscure origin c. 40 AD, with fewer than 1,000 followers, to being the majority religion of the entire Roman Empire by AD 400, has been examined through a wide variety of historiographical approaches.

Paganism is commonly used to refer to various religions that existed during Antiquity and the Middle Ages, such as the Greco-Roman religions of the Roman Empire, including the Roman imperial cult, the various mystery religions, religious philosophies such as Neoplatonism and Gnosticism, and more localized ethnic religions practiced both inside and outside the empire. During the Middle Ages, the term was also adapted to refer to religions practiced outside the former Roman Empire, such as Germanic paganism, Egyptian paganism and Baltic paganism.

Christians were persecuted throughout the Roman Empire, beginning in the 1st century AD and ending in the 4th century. Originally a polytheistic empire in the traditions of Roman paganism and the Hellenistic religion, as Christianity spread through the empire, it came into ideological conflict with the imperial cult of ancient Rome. Pagan practices such as making sacrifices to the deified emperors or other gods were abhorrent to Christians as their beliefs prohibited idolatry. The state and other members of civic society punished Christians for treason, various rumored crimes, illegal assembly, and for introducing an alien cult that led to Roman apostasy. The first, localized Neronian persecution occurred under Emperor Nero in Rome. A number of mostly localized persecutions occurred during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. After a lull, persecution resumed under Emperors Decius and Trebonianus Gallus. The Decian persecution was particularly extensive. The persecution of Emperor Valerian ceased with his notable capture by the Sasanian Empire's Shapur I at the Battle of Edessa during the Roman–Persian Wars. His successor, Gallienus, halted the persecutions.

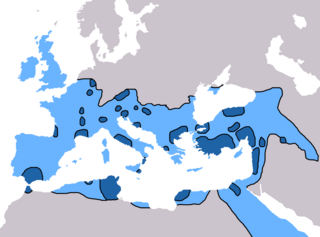

Christianity began as a Second Temple Judaic sect in the 1st century in the Roman province of Judea, from where it spread throughout and beyond the Roman Empire.

Christianity in the 4th century was dominated in its early stage by Constantine the Great and the First Council of Nicaea of 325, which was the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787), and in its late stage by the Edict of Thessalonica of 380, which made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire.

Christianity in late antiquity traces Christianity during the Christian Roman Empire — the period from the rise of Christianity under Emperor Constantine, until the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end-date of this period varies because the transition to the sub-Roman period occurred gradually and at different times in different areas. One may generally date late ancient Christianity as lasting to the late 6th century and the re-conquests under Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, though a more traditional end-date is 476, the year in which Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus, traditionally considered the last western emperor.

In the year before the Council of Constantinople in 381, the Trinitarian version of Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians as the Roman Empire's state religion. Historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.

Persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire began during the reign of Constantine the Great in the military colony of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), when he destroyed a pagan temple for the purpose of constructing a Christian church. Rome had periodically confiscated church properties, and Constantine was vigorous in reclaiming them whenever these issues were brought to his attention. Christian historians alleged that Hadrian had constructed a temple to Venus on the site of the crucifixion of Jesus on Golgotha hill in order to suppress Christian veneration there. Constantine used that to justify the temple's destruction, saying he was simply reclaiming the property. Using the vocabulary of reclamation, Constantine acquired several more sites of Christian significance in the Holy Land.

Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation looks at religious change in the Roman Empire's first three centuries through the lens of diffusion of innovations, a sociological theory popularized by Everett Rogers in 1962. Diffusion of innovation is a process of communication that takes place over time, among those within a social system, that explains how, why, and when new ideas spread. In this theory, an innovation's success or failure is dependent upon the characteristics of the innovation itself, the adopters, what communication channels are used, time, and the social system in which it all happens.