DomHenrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu, better known as Prince Henry the Navigator, was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15th-century European maritime discoveries and maritime expansion. Through his administrative direction, he is regarded as the main initiator of what would be known as the Age of Discovery. Henry was the fourth child of the Portuguese King John I, who founded the House of Aviz.

The history of the Kingdom of Portugal from the Illustrious Generation of the early 15th century to the fall of the House of Aviz in the late 16th century has been named the "Portuguese golden age" and the "Portuguese Renaissance". During this period, Portugal was the first European power to begin building a colonial empire as Portuguese sailors and explorers discovered an eastern route to India as well as several Atlantic archipelagos and colonized the African coast and Brazil. They also explored the Indian Ocean and established trading routes throughout most of southern Asia, sending the first direct European maritime trade and diplomatic missions to Ming China and to Japan, at the same time installing trading posts and the most important colony: Portuguese Macau. The Portuguese Renaissance produced a plethora of poets, historians, critics, theologians, and moralists. The Cancioneiro Geral by Garcia de Resende is taken to mark the transition from Old Portuguese to the modern Portuguese language.

Jehudà Cresques, also known as Jafudà Cresques, Jaume Riba, and Cresques lo Juheu, was a converso cartographer in the early 15th century.

Conquistadors or conquistadores were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, Oceania, Africa, and Asia, colonizing and opening trade routes. They brought much of the Americas under the dominion of Spain and Portugal.

The caravel is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing windward (beating). Caravels were used by the Portuguese and Castilians for the oceanic exploration voyages during the 15th and 16th centuries, during the Age of Discovery.

Antillia is a phantom island that was reputed, during the 15th-century age of exploration, to lie in the Atlantic Ocean, far to the west of Portugal and Spain. The island also went by the name of Isle of Seven Cities.

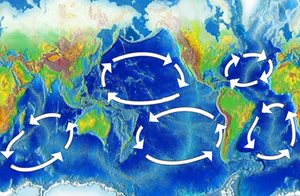

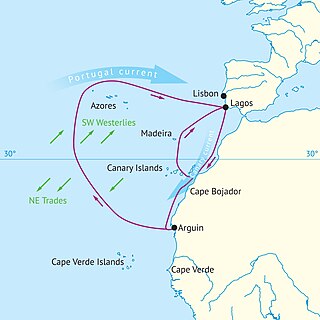

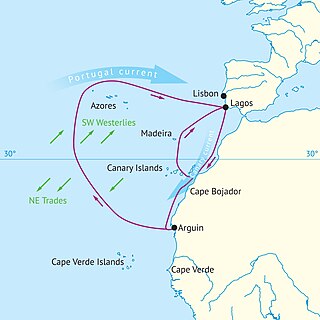

Volta do mar, volta do mar largo, or volta do largo is a navigational technique perfected by Portuguese navigators during the Age of Discovery in the late fifteenth century, using the dependable phenomenon of the great permanent wind circle, the North Atlantic Gyre. This was a major step in the history of navigation, when an understanding of winds in the age of sail was crucial to success: the European sea empires would not have been established without an understanding of the trade winds.

Diogo Ribeiro was a Portuguese cartographer and explorer who worked most of his life in Spain where he was known as Diego Ribero. He worked on the official maps of the Padrón Real from 1518 to 1532. He also made navigation instruments, including astrolabes and quadrants.

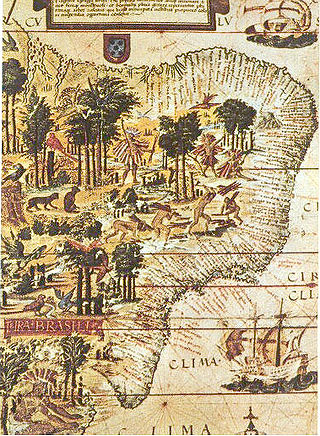

Pedro Reinel was a Portuguese cartographer. Between 1485 and 1519 Reinel served three Portuguese kings: João II, Manuel I and João III. He and his son, Jorge Reinel, were among the most renowned cartographers of their era, a period when European knowledge of geography and cartography were expanding rapidly. There is some evidence he was of African descent. Historian Rafael Moreira believes Reinel's father was an ivory carver brought from West Africa to serve in the royal workshops.

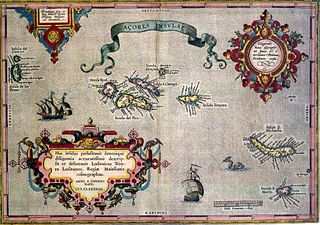

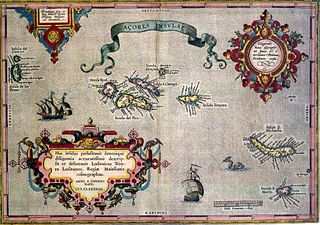

The following article describes the history of the Azores.

The history of navigation, or the history of seafaring, is the art of directing vessels upon the open sea through the establishment of its position and course by means of traditional practice, geometry, astronomy, or special instruments. Many peoples have excelled as seafarers, prominent among them the Austronesians, the Harappans, the Phoenicians, the Iranians, the ancient Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the ancient Indians, the Norse, the Chinese, the Venetians, the Genoese, the Hanseatic Germans, the Portuguese, the Spanish, the English, the French, the Dutch, and the Danes.

Portuguese maritime exploration resulted in the numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European exploration, chronicling and mapping the coasts of Africa and Asia, then known as the East Indies, and Canada and Brazil, in what came to be known as the Age of Discovery.

"Majorcan cartographic school" is the term coined by historians to refer to the collection of predominantly Jewish cartographers, cosmographers and navigational instrument-makers and some Christian associates that flourished in Majorca in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries until the expulsion of the Jews. The label is usually inclusive of those who worked in Catalonia. The Majorcan school is frequently contrasted with the contemporary Italian cartography school.

Lopo Homem was a 16th-century Portuguese cartographer and cosmographer based in Lisbon and best known for his work on the Miller Atlas.

The Seventh India Armada was assembled in 1505 on the order of King Manuel I of Portugal and placed under the command of D. Francisco de Almeida, the first Portuguese Viceroy of the Indies. The 7th Armada set out to secure the dominance of the Portuguese navy over the Indian Ocean by establishing a series of coastal fortresses at critical points – Sofala, Kilwa, Anjediva, Cannanore – and reducing cities perceived to be local threats.

Due to centuries of constant conflict, warfare and daily life in the Iberian Peninsula were interlinked. Small, lightly equipped armies were maintained at all times. The near-constant state of war resulted in a need for maritime experience, ship technology, power, and organization. This led the Crowns of Aragon, Portugal, and later Castile, to put their efforts into the sea.

Zuane Pizzigano, was a 15th-century Venetian cartographer. He is the author of a famous 1424 portolan chart, the first known to depict the phantom islands of the purported Antillia archipelago, in the north Atlantic Ocean.

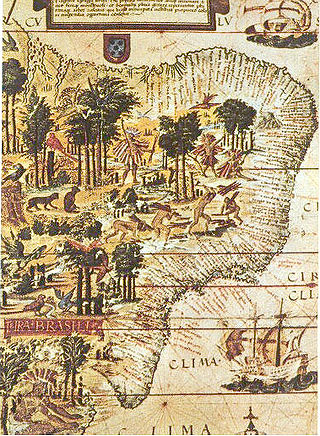

The Miller Atlas, also known as Lopo Homem-Reineis Atlas, is a richly illustrated Portuguese partial world atlas dated from 1519, including a dozen charts. It is a joint work of the cartographers Lopo Homem, Pedro Reinel and Jorge Reinel, and illustrated by miniaturist António de Holanda.

The square-rigged caravel, was a sailing ship created by the Portuguese in the second half of the fifteenth century. A much larger version of the caravel, its use was most notorious beginning in the end of that century. The square-rigged caravel held a notable role in the Portuguese expansion during the age of discovery, especially in the first half of the sixteenth century, for its exceptional maneuverability and combat capabilities. This ship was also sometimes adopted by other European powers. The hull was galleon-shaped, and some experts consider this vessel a forerunner of the fighting galleon, by the name of caravela de armada.

The School of Sagres, also called Court of Sagres is supposed to have been a group of figures associated with fifteenth century Portuguese navigation, gathered by prince Henry of Portugal in Sagres near Cape St. Vincent, the southwestern end of the Iberian Peninsula, in the Algarve.